Biography

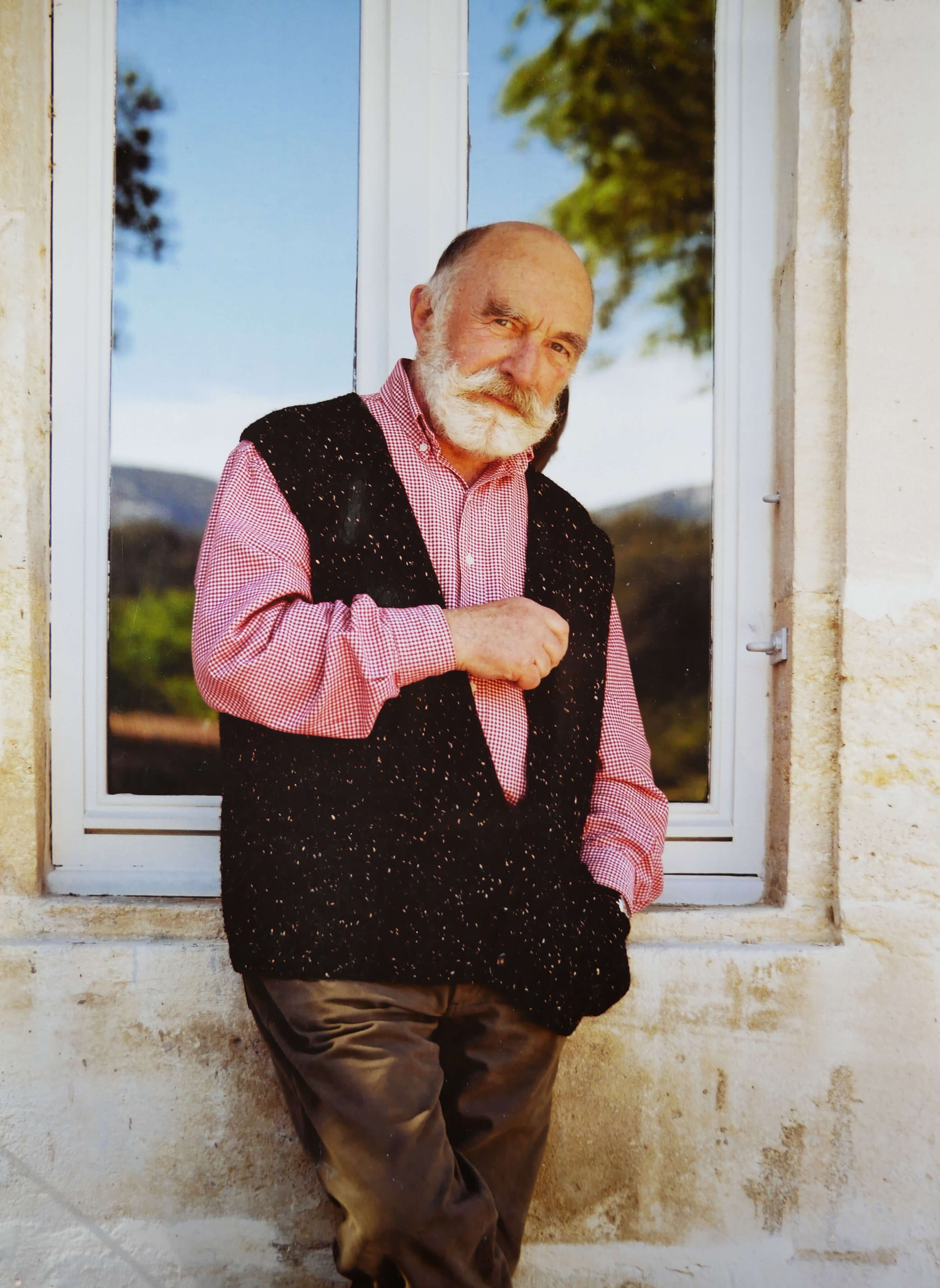

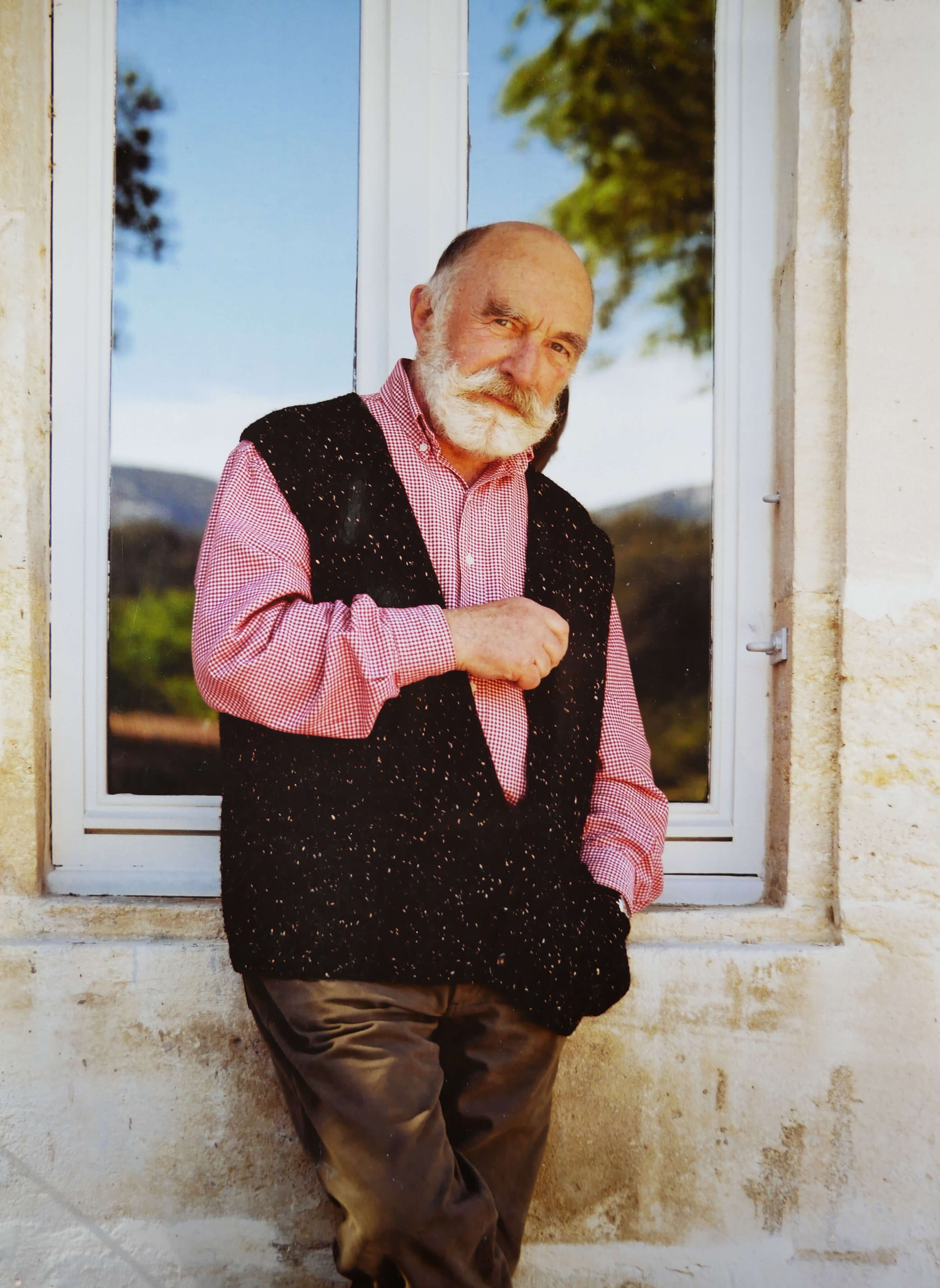

French composer born October 27th 1927, died November 21st 2013 in Paris. The majority of his highly diverse body of work is dedicated to electroacoustic music, of which he is one of the pioneers. Forever in search of new sound material, he experimented throughout his 80-strong corpus of concert pieces with new and original production techniques to highlight the multiple aspects of the nature of sound. He also wrote “applied” works for radio, television, cinema, ballet, advertising and the stage, as well as opening and end credits and jingles such as the one for Paris-Charles de Gaulle Airport.

His father, an editor at Editions Gautier-Languereau and author of a few of the Bécassine comic strips, died two months after Bernard was born. Following his mother's second marriage, Parmegiani grew up between two pianos – that of his virtuoso father-in-law, and that of his teacher mother. From his bedroom he heard on one side the daily scales and Clementi sonatas, and on the other the pianistic repertory of Fauré and Debussy. Thorough ear training which would acquaint him with the state of listening essential to his composition work later.

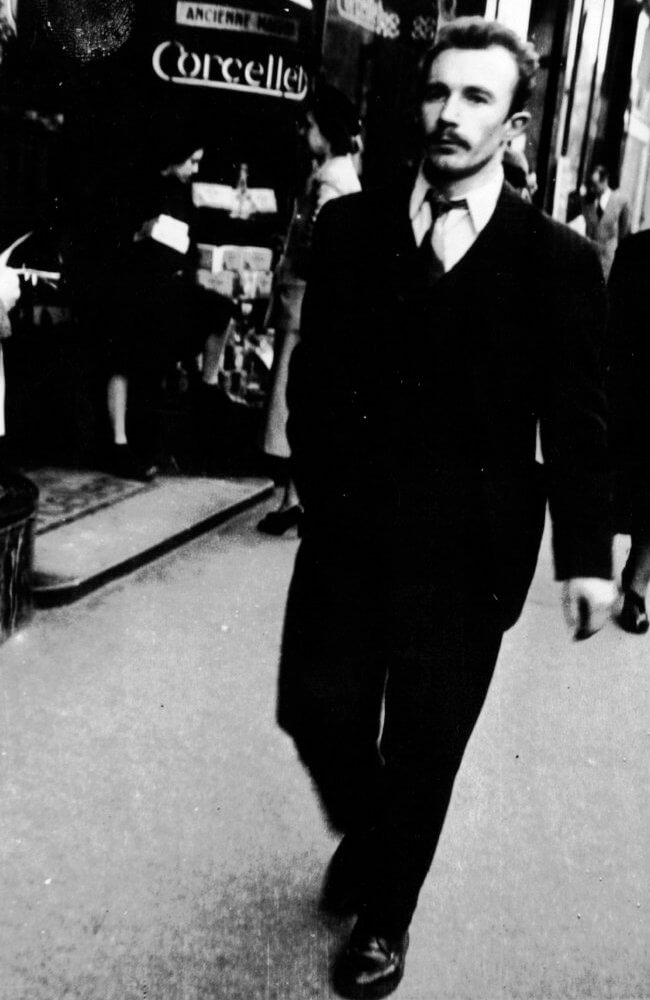

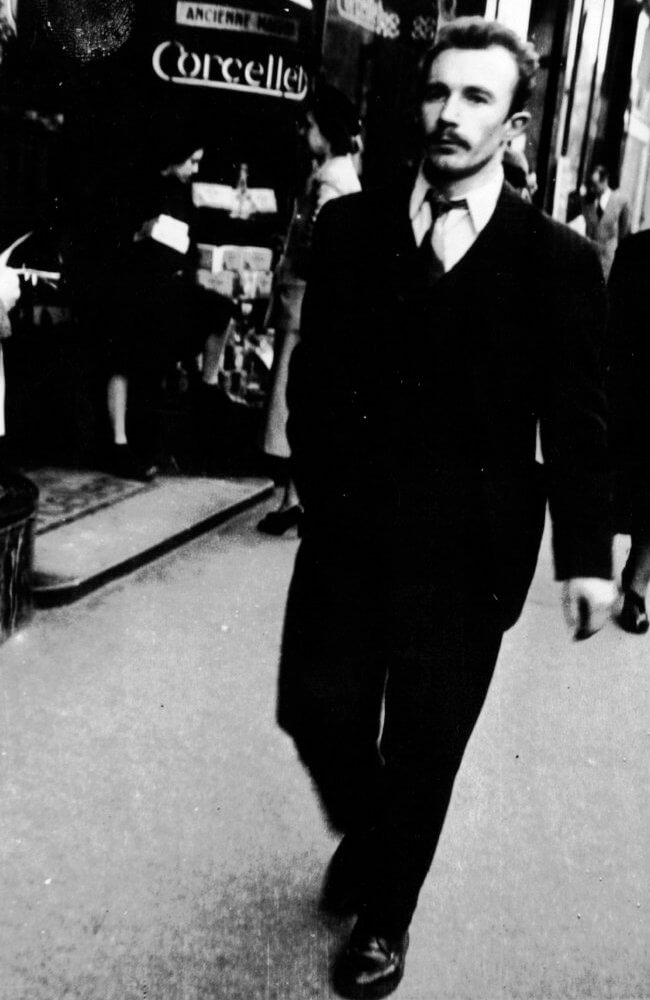

In the Army Cinema Service he learnt the various necessary sound recording techniques, and in 1954 began working in radio, quickly becoming a sound engineer in television. He practiced mime at the same time, first off with Maximilien Decroux and later with Jacques Lecoq. This taught him about physical space and flexibility within it, vital elements in the architecture of his sound world later on.

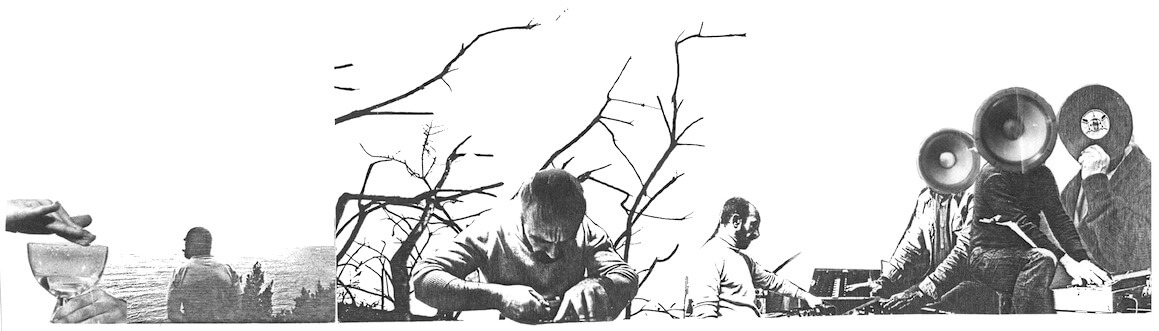

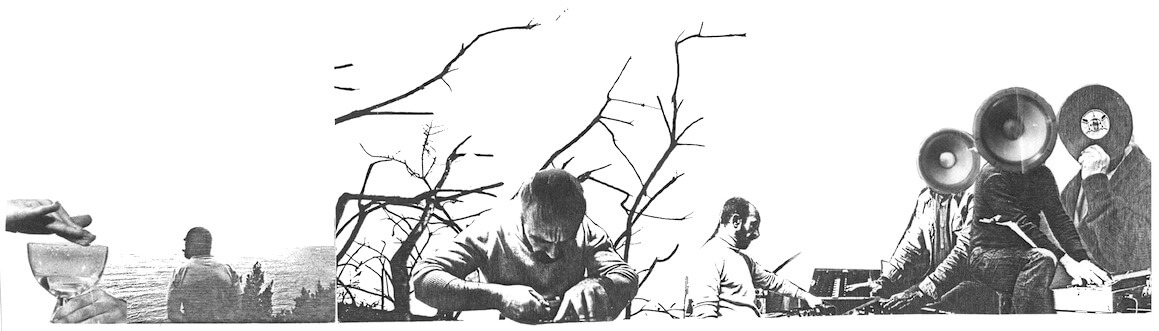

During this period Parmegiani gave himself over passionately to a hobby which would presage the composer's approach to sound. He cut up, stuck together, and assembled newspaper images to create surreal, tongue-in-cheek photomontages.

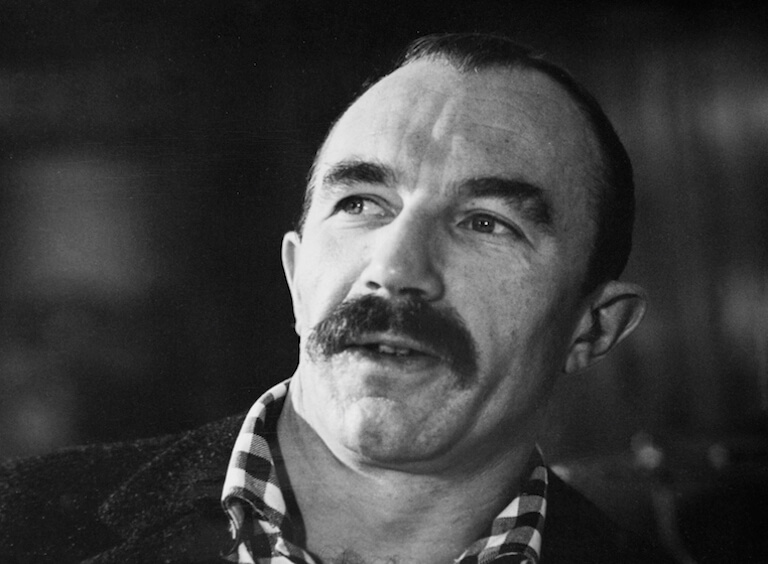

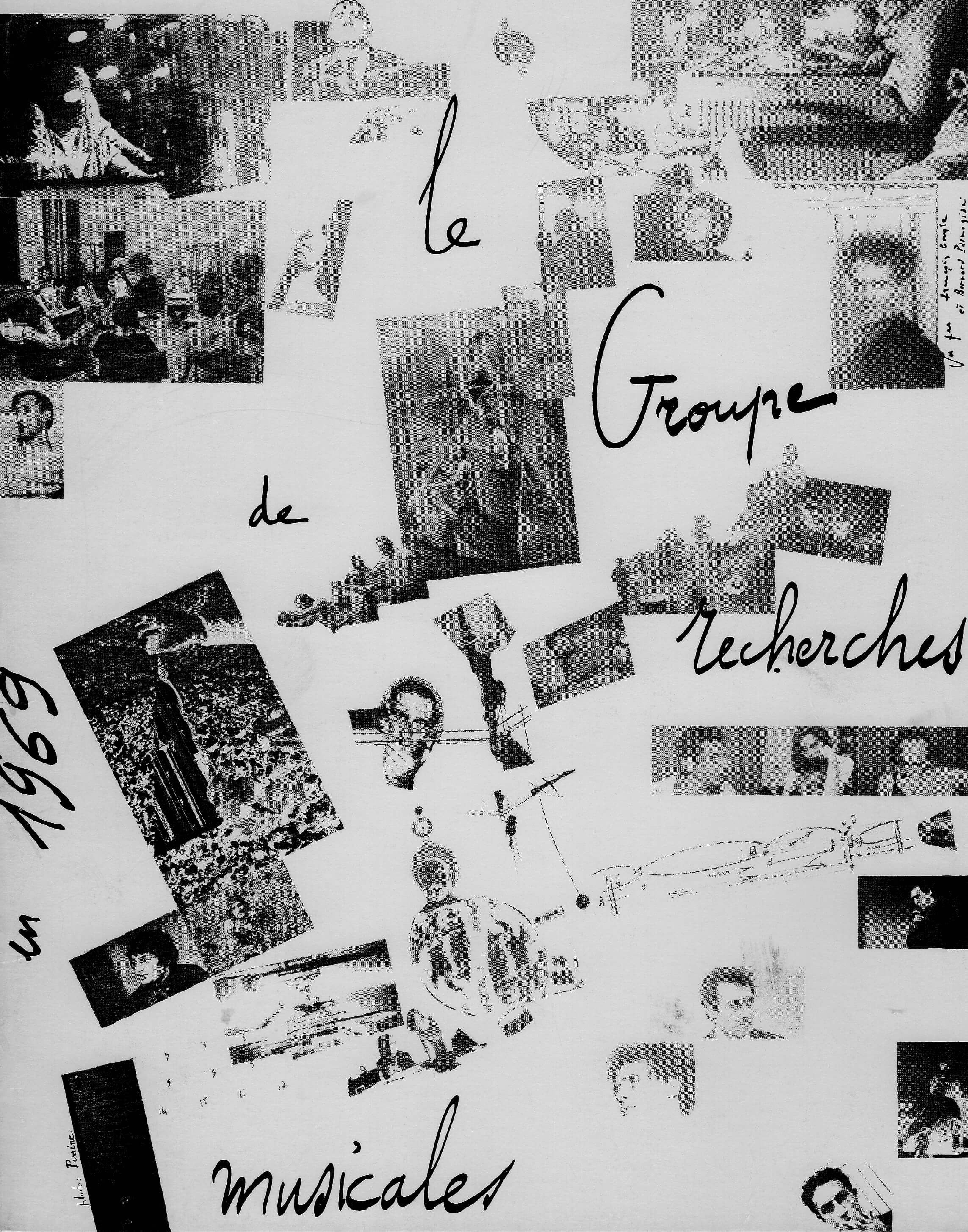

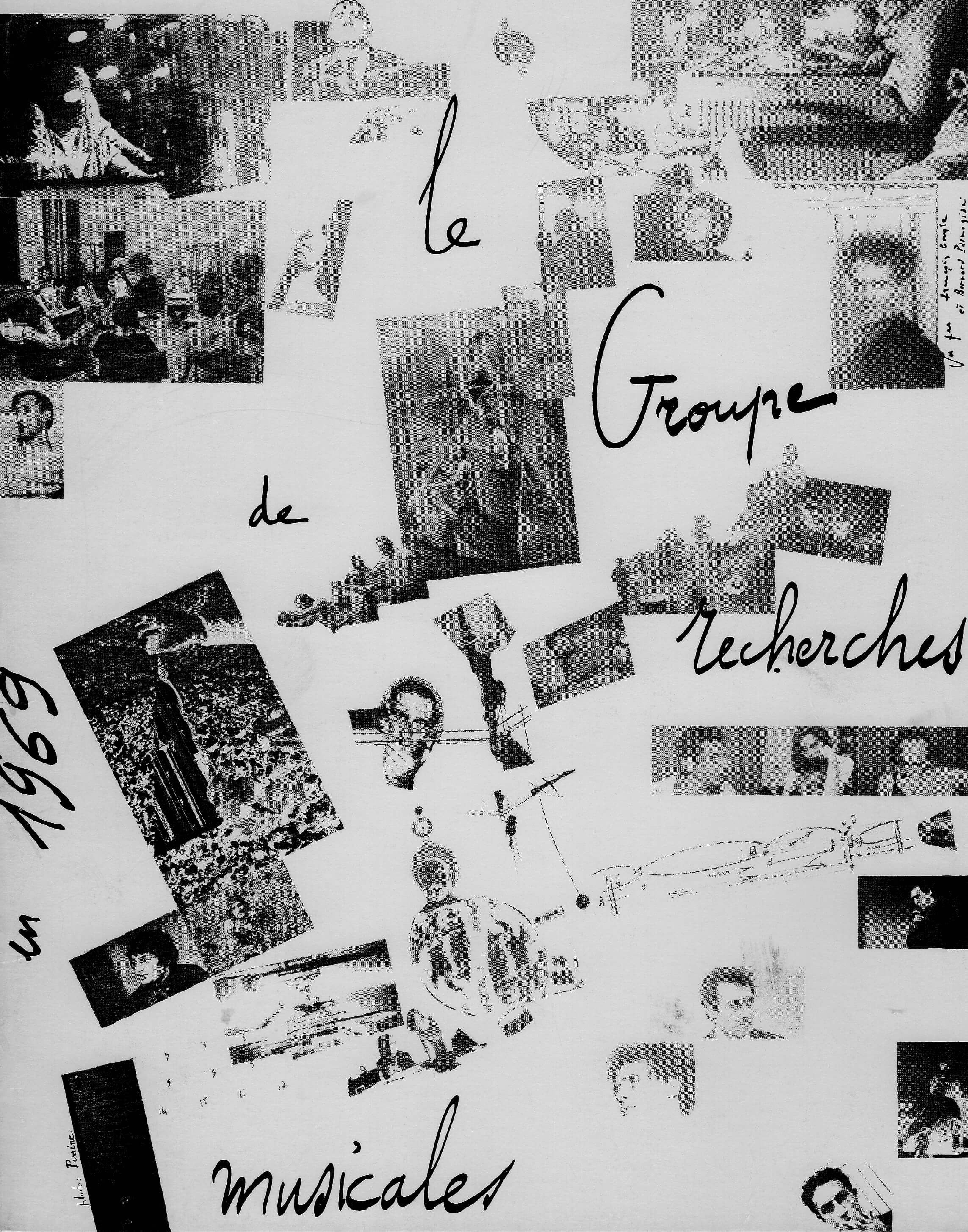

At the same time he practiced his scales by tinkering with short sonic passages on the radio. He worked with André Almuro who wrote a piece with what would become a premonitory title for Parmegiani, De Natura Rerum, in reference to Lucretius. Pierre Schaeffer came to listen to the work in progress at the little studio at the Maison des Lettres and invited Almuro to his Club d'Essai, in the wake of which Parmegiani joined the GRM as sound technician and assisted already-established composers. He quit television to continue the training course at the GRM and made sound illustrations for short films produced by the Research Service.

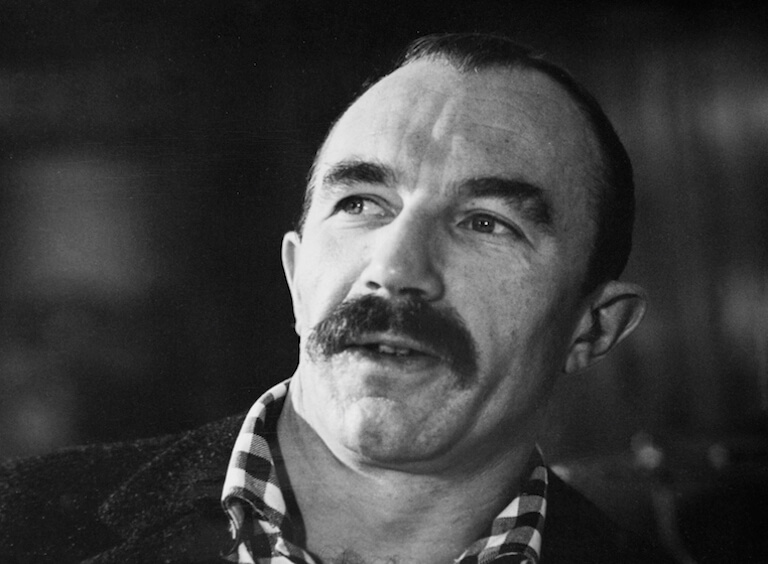

After composing an Etude in 1962 which marked the end of his training, it was time to take the leap. Schaeffer once again plays a role in his fate. He demands Parmegiani to choose between mime and music, inviting him to take part in the 'Collective Concert' side by side with the composers whom he had previously been assistant to. After listening to his short piece Alternances, violinist Devy Erlih commissions Parmegiani to write a piece for violin and tape. The sound material was made up entirely of violin sounds, reworked, transposed, mixed up, and it required over a year's “embroidery work”, as Parmegiani referred to it. This experience, new at the time in the world of electroacoustic music, was necessary for both composers striving for consistency in the material between the electroacoustic and instrumental parts. The latter was written afterwards by Erlih, and Violostries became the first crucial work of Parmegiani's repertory. It would be followed by fifty years of incessant research grappling with sound.

Throughout a long life of uninterrupted musical creation, Parmegiani tried his hand at every genre. Once named the head of the Sound/Image department by Schaeffer, he met a great deal of filmmakers, many of whom were painters that found the necessary means to experimental animation at the Research Service; to name but a few, Valerian Borowczyck, Peter Foldés, Piotr Kamler, and Robert Lapoujade (whose Le Socrate Parmegiani wrote the music for). He also worked with directors known to the small as well as the big screen, such as Jacques Baratier, Cavalcanti, P. Condroyer, J.E. Jeanneson, P. Kast, Peter Kassovitz, G. Patris, M. Sibra, and M. Treguer; with choreographers such as Christine Bastin, Vittorio Biagi, Françoise and Dominique Dupuy, Michel Descombey, Jacques Garnier, and Brigitte Lefêvre; with producers such as A. Bourseiller, R. Blin, J. Dasté, M. Serreau, and C. Régy; and radio show producers including Robert Arnaud, Charlotte Latigrat, and Georges Léon...

He wrote theme tunes for shows and music for adverts including for Interactualités (1960-65), France 3 news (1972-74), France Culture (1975-85), the C'est-à-dire TV magazine (1975-76), France Culture's Poésie Ininterrompue (1975-78), and the world's most famous electroacoustic music, the jingle for the Roissy Charles de Gaulle Airport, used for over 35 years.

Solid training for tackling the problems posed by musical forms constrained by a film's framework and someone else's content.

These diverse practices were put to good use in Parmegiani's acousmatic works.

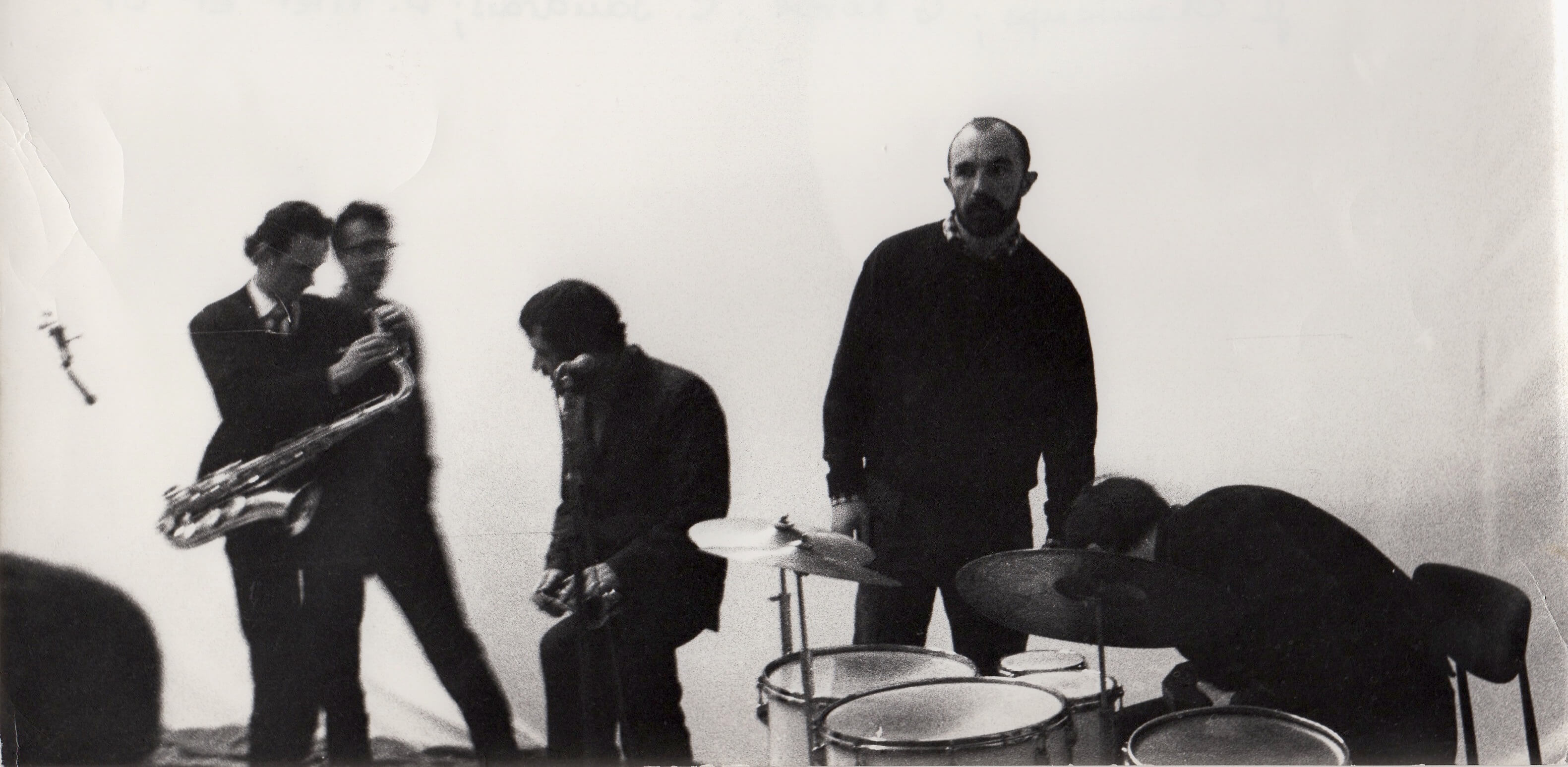

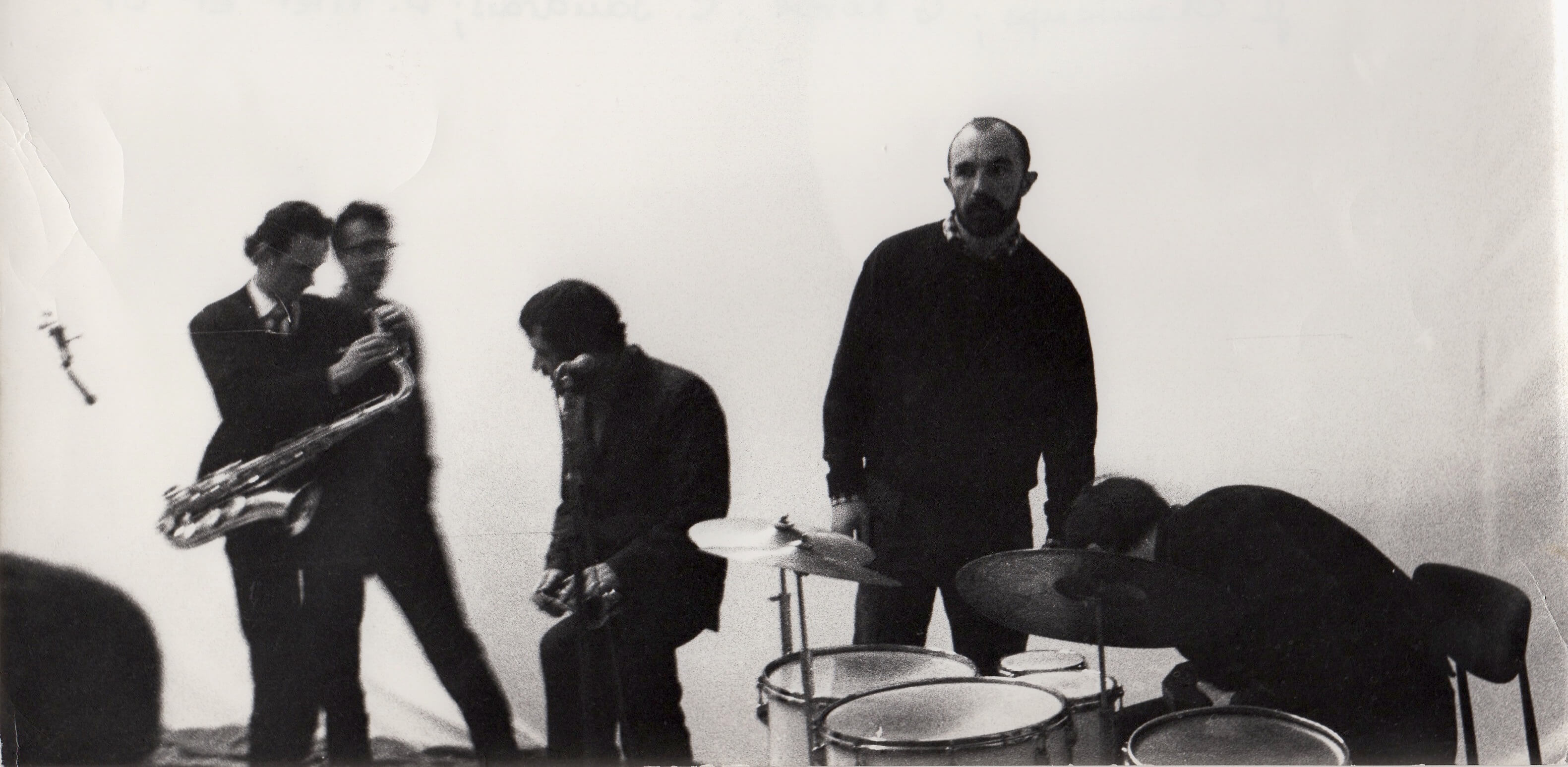

In L'instant mobile (1966), he explores the possibilities of 4-track spatialization; in Capture Ephémère (1967-68), he composes a score of specific sounds for each of the four tracks, “as for a quartet”. In Jazzex (1966), the pre-composed sounds on tape come up against the live free jazz musicians J-L. Chautemps, B. Vitet, C. Sautais, G. Rovère – a dialogue he experiments again with later in Le Diable à Quatre, reuniting M. Portal, J-F. Jenny-Clark, J-P. Drouet and Parmegiani in 1971.

Then comes the repetitive period – L'Oeil Ecoute, La Roue Ferris, Pour en finir avec le pouvoir d'Orphée (1972), and not forgetting Et après (1973) with Michel Portal on the bandoneon, plus the various collages and the Pop series.

From 1972 to '73, Parmegiani attempted something new – working with a text (and what a text!) - Dante's The Divine Comedy. No less than two composers would be needed to undertake the great Italian poet's long rite of passage. For Parmegiani, Hell; and for François Bayle, Purgatory. Both then finish the maiden voyage together in an evanescent Paradise.

After this trip to Hell and back, Parmegiani took a break from the abundant musical production characteristic of his work and focused more deeply and methodically on the nature of sound itself. This almost entomological approach in which the attentive exploration of sound, now frequently described by the composer as a “sound being”, becomes a part of his trademark style. De Natura Sonorum (1975-76), comprising 12 movements separated into 2 sections, marks a major moment in electroacoustic music which not only ushers in a new era for the composer but also a new method of composition (cf. l’Envers d’une œuvre, De Natura Sonorum by Philippe Mion, Jean-Jacques Nattiez, Jean Christophe Thomas, INA_GRM/Buchet.Chastel, 1982).

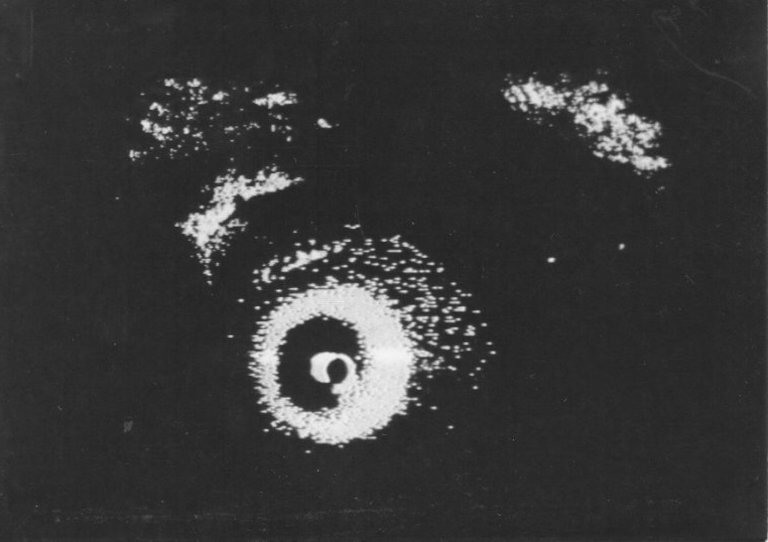

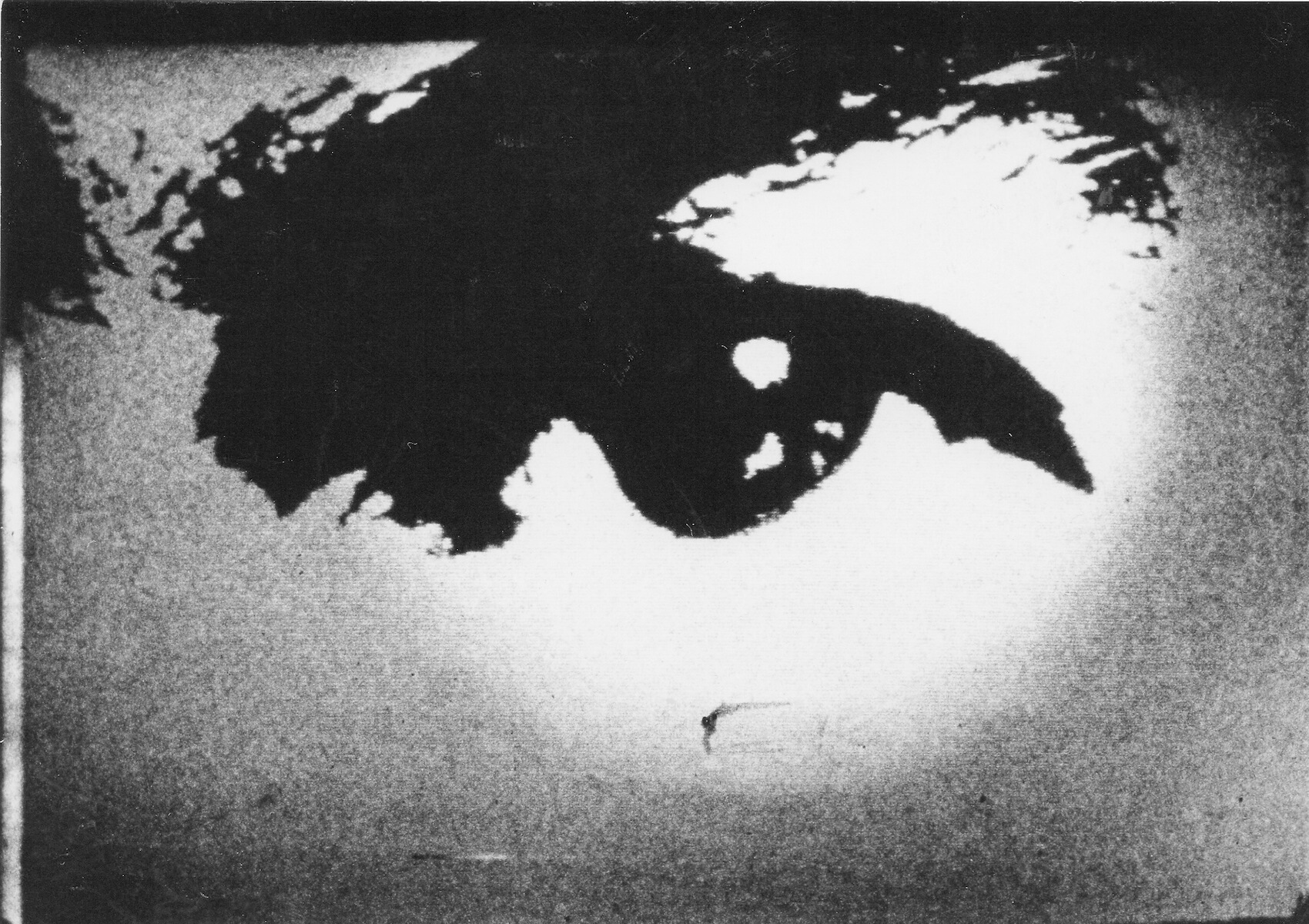

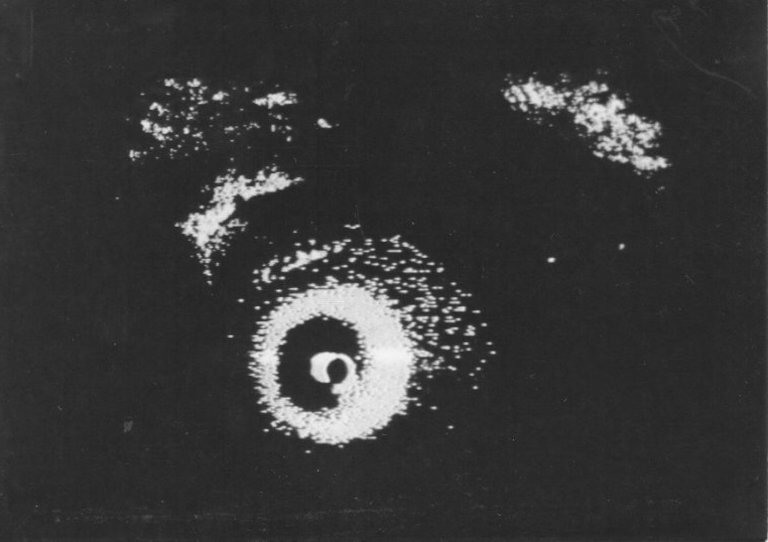

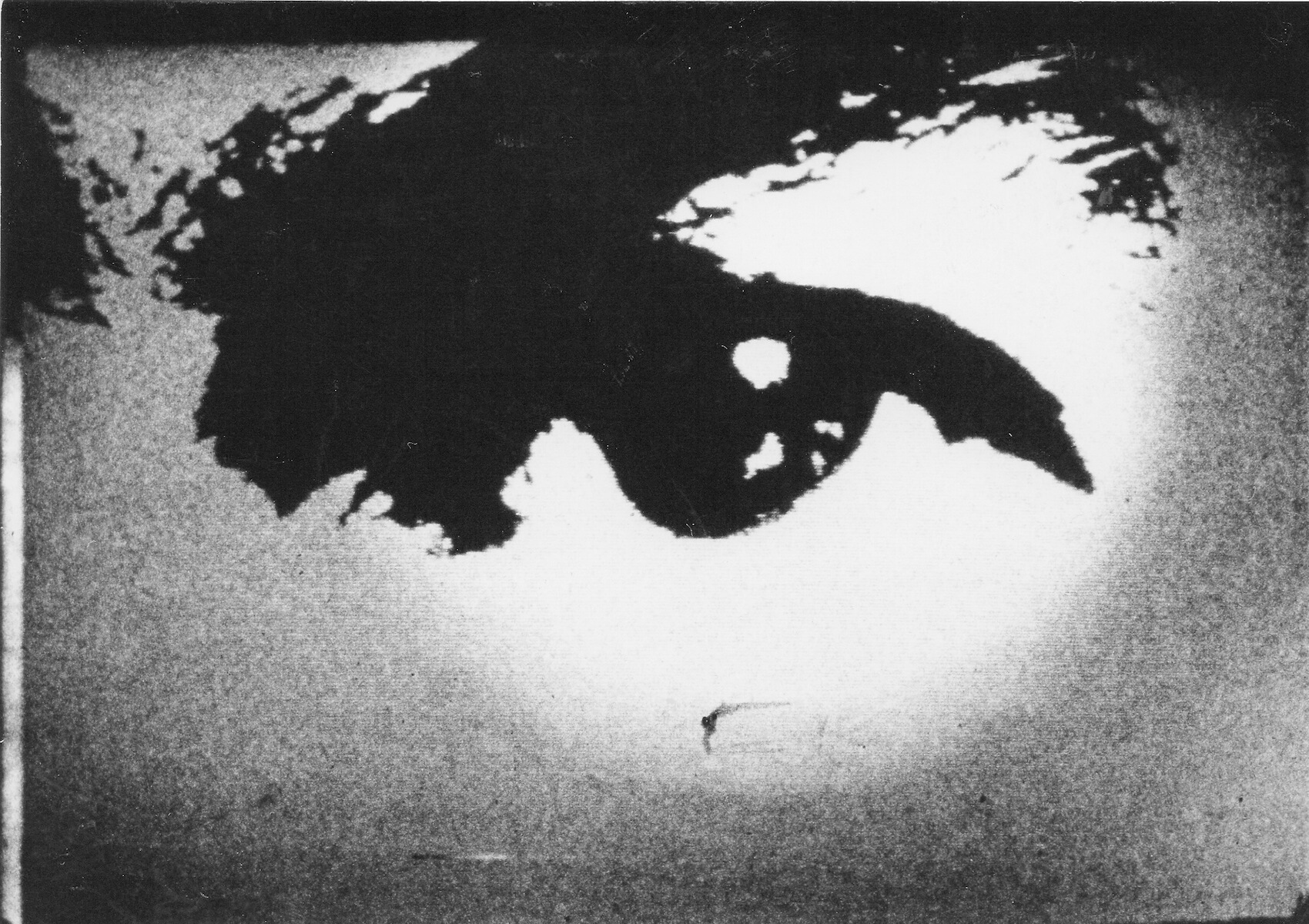

Elsewhere, Parmegiani began reversing the role of music as accompaniment to images created by others. Music would no longer be subject to the visual, but precede it. Sounds made long ago by musique concrète composers would be applied to video made by Parmegiani himself. L'Oeil Ecoute (1971-72) is accompanied by a video created by the composer using some of Valerian Borowczyck's photos (1973). Two more pieces would follow:- L'Ecran transparent co-produced with the WDR in 1973, and Jeux d'artifices in 1979.

Not content simply sowing seeds in one field of expertise, the composer hovered around another at the same time: the stage. The first attempt at musical theatre came in 1973 with Trio, co-written with Michel Chion, who also acted in it. Then, in 1979, a musical “happening” called Mess Media Sons, followed by two pieces with Gérard Buquet, Tuba-ci, Tuba-là (1981) and Tuba Raga (1982), in which the two accomplices relish in a shared taste for irreverent comedy. Finally, l'Echo du miroir in 1980 – an audio-visual show featuring works by the painter Michel Moy.

Henceforth, Parmegiani's work would cross over many domains. The concert pieces of the '80's and the first half of the '90's responded to the need for more vast undertakings, and are broken up into chapters. Les Exercismes I, II, III, IV group together four pieces which continue on the same route opened up by De Natura Sonorum and use new techniques such as those featured in UPIC. La Création du Monde is a vast saga clocking in at 73 minutes, comprising 3 pieces, and was awarded a Victoire de la Musique in 1989. The Plain-temps series also makes up a trilogy:- Le Présent composé in 1991, Entre-temps in 1992, and Plain temps in 1993.

Then, from 1996 onwards, Parmegiani pursued short form compositions as a more suitable approach to his work. The possibilities brought about by developments in music technology allowed him to revisit certain familiar themes:- Sonares (1996) is concerned with the meeting and mixing of natural and synthetic sounds; in La mémoire des sons (2000-2001), “the sounds of the past contribute to the composition of the present”; and Rêveries (2007), his last piece, guides the listener through a 14-minute tour of his past works.

Throughout this period, Parmegiani continued to work within various different musical genres. Film music includes V. Borowczyck's Dr. Jekyll et les femmes; for television he wrote for four episodes of Mario Ruspoli's L'Art au Monde des ténèbres (1982); he wrote the text as well as the music for the radio show E pericoloso sporgersi; for ballet with Vittorio Biagi's Rouge-mort and the Opéra de Nice; and last but not least, his musical happenings such as Démons et des mots with the haute-contre singer and actor Frank Royon Le Mée...

This career path is outlined in more detail in Eveylne Gayou's interview with Bernard Parmegiani, extracts of which can be found on the site under the title Mots de l'immédiat (in Portaits Polychromes, BP, INA/GRM).

Parmegiani's work has received many awards :

- 1976 Prix Italia Laureate

- 1979 Disque Français Grand Prix

- 1981 Prix de la Sacem

- 1990 5th Victoires de la Musique – Contemporary Music Prize

- 1991 Bourges International Competition – Prix Magister

- 1993 Ars Electronica - Linz (Autriche), Grand Prix Golden Nika

- 2006 Quartz électronique – Pierre Schaeffer Memorial Prize

- 2010 Prix Charles Cros (Prize of the President of the Republic) for the 12-disk INA/GRM boxset.

Biography

French composer born October 27th 1927, died November 21st 2013 in Paris. The majority of his highly diverse body of work is dedicated to electroacoustic music, of which he is one of the pioneers. Forever in search of new sound material, he experimented throughout his 80-strong corpus of concert pieces with new and original production techniques to highlight the multiple aspects of the nature of sound. He also wrote “applied” works for radio, television, cinema, ballet, advertising and the stage, as well as opening and end credits and jingles such as the one for Paris-Charles de Gaulle Airport.

His father, an editor at Editions Gautier-Languereau and author of a few of the Bécassine comic strips, died two months after Bernard was born. Following his mother's second marriage, Parmegiani grew up between two pianos – that of his virtuoso father-in-law, and that of his teacher mother. From his bedroom he heard on one side the daily scales and Clementi sonatas, and on the other the pianistic repertory of Fauré and Debussy. Thorough ear training which would acquaint him with the state of listening essential to his composition work later.

In the Army Cinema Service he learnt the various necessary sound recording techniques, and in 1954 began working in radio, quickly becoming a sound engineer in television. He practiced mime at the same time, first off with Maximilien Decroux and later with Jacques Lecoq. This taught him about physical space and flexibility within it, vital elements in the architecture of his sound world later on.

During this period Parmegiani gave himself over passionately to a hobby which would presage the composer's approach to sound. He cut up, stuck together, and assembled newspaper images to create surreal, tongue-in-cheek photomontages.

At the same time he practiced his scales by tinkering with short sonic passages on the radio. He worked with André Almuro who wrote a piece with what would become a premonitory title for Parmegiani, De Natura Rerum, in reference to Lucretius. Pierre Schaeffer came to listen to the work in progress at the little studio at the Maison des Lettres and invited Almuro to his Club d'Essai, in the wake of which Parmegiani joined the GRM as sound technician and assisted already-established composers. He quit television to continue the training course at the GRM and made sound illustrations for short films produced by the Research Service.

After composing an Etude in 1962 which marked the end of his training, it was time to take the leap. Schaeffer once again plays a role in his fate. He demands Parmegiani to choose between mime and music, inviting him to take part in the 'Collective Concert' side by side with the composers whom he had previously been assistant to. After listening to his short piece Alternances, violinist Devy Erlih commissions Parmegiani to write a piece for violin and tape. The sound material was made up entirely of violin sounds, reworked, transposed, mixed up, and it required over a year's “embroidery work”, as Parmegiani referred to it. This experience, new at the time in the world of electroacoustic music, was necessary for both composers striving for consistency in the material between the electroacoustic and instrumental parts. The latter was written afterwards by Erlih, and Violostries became the first crucial work of Parmegiani's repertory. It would be followed by fifty years of incessant research grappling with sound.

Throughout a long life of uninterrupted musical creation, Parmegiani tried his hand at every genre. Once named the head of the Sound/Image department by Schaeffer, he met a great deal of filmmakers, many of whom were painters that found the necessary means to experimental animation at the Research Service; to name but a few, Valerian Borowczyck, Peter Foldés, Piotr Kamler, and Robert Lapoujade (whose Le Socrate Parmegiani wrote the music for). He also worked with directors known to the small as well as the big screen, such as Jacques Baratier, Cavalcanti, P. Condroyer, J.E. Jeanneson, P. Kast, Peter Kassovitz, G. Patris, M. Sibra, and M. Treguer; with choreographers such as Christine Bastin, Vittorio Biagi, Françoise and Dominique Dupuy, Michel Descombey, Jacques Garnier, and Brigitte Lefêvre; with producers such as A. Bourseiller, R. Blin, J. Dasté, M. Serreau, and C. Régy; and radio show producers including Robert Arnaud, Charlotte Latigrat, and Georges Léon...

He wrote theme tunes for shows and music for adverts including for Interactualités (1960-65), France 3 news (1972-74), France Culture (1975-85), the C'est-à-dire TV magazine (1975-76), France Culture's Poésie Ininterrompue (1975-78), and the world's most famous electroacoustic music, the jingle for the Roissy Charles de Gaulle Airport, used for over 35 years.

Solid training for tackling the problems posed by musical forms constrained by a film's framework and someone else's content.

These diverse practices were put to good use in Parmegiani's acousmatic works.

In L'instant mobile (1966), he explores the possibilities of 4-track spatialization; in Capture Ephémère (1967-68), he composes a score of specific sounds for each of the four tracks, “as for a quartet”. In Jazzex (1966), the pre-composed sounds on tape come up against the live free jazz musicians J-L. Chautemps, B. Vitet, C. Sautais, G. Rovère – a dialogue he experiments again with later in Le Diable à Quatre, reuniting M. Portal, J-F. Jenny-Clark, J-P. Drouet and Parmegiani in 1971.

Then comes the repetitive period – L'Oeil Ecoute, La Roue Ferris, Pour en finir avec le pouvoir d'Orphée (1972), and not forgetting Et après (1973) with Michel Portal on the bandoneon, plus the various collages and the Pop series.

From 1972 to '73, Parmegiani attempted something new – working with a text (and what a text!) - Dante's The Divine Comedy. No less than two composers would be needed to undertake the great Italian poet's long rite of passage. For Parmegiani, Hell; and for François Bayle, Purgatory. Both then finish the maiden voyage together in an evanescent Paradise.

After this trip to Hell and back, Parmegiani took a break from the abundant musical production characteristic of his work and focused more deeply and methodically on the nature of sound itself. This almost entomological approach in which the attentive exploration of sound, now frequently described by the composer as a “sound being”, becomes a part of his trademark style. De Natura Sonorum (1975-76), comprising 12 movements separated into 2 sections, marks a major moment in electroacoustic music which not only ushers in a new era for the composer but also a new method of composition (cf. l’Envers d’une œuvre, De Natura Sonorum by Philippe Mion, Jean-Jacques Nattiez, Jean Christophe Thomas, INA_GRM/Buchet.Chastel, 1982).

Elsewhere, Parmegiani began reversing the role of music as accompaniment to images created by others. Music would no longer be subject to the visual, but precede it. Sounds made long ago by musique concrète composers would be applied to video made by Parmegiani himself. L'Oeil Ecoute (1971-72) is accompanied by a video created by the composer using some of Valerian Borowczyck's photos (1973). Two more pieces would follow:- L'Ecran transparent co-produced with the WDR in 1973, and Jeux d'artifices in 1979.

Not content simply sowing seeds in one field of expertise, the composer hovered around another at the same time: the stage. The first attempt at musical theatre came in 1973 with Trio, co-written with Michel Chion, who also acted in it. Then, in 1979, a musical “happening” called Mess Media Sons, followed by two pieces with Gérard Buquet, Tuba-ci, Tuba-là (1981) and Tuba Raga (1982), in which the two accomplices relish in a shared taste for irreverent comedy. Finally, l'Echo du miroir in 1980 – an audio-visual show featuring works by the painter Michel Moy.

Henceforth, Parmegiani's work would cross over many domains. The concert pieces of the '80's and the first half of the '90's responded to the need for more vast undertakings, and are broken up into chapters. Les Exercismes I, II, III, IV group together four pieces which continue on the same route opened up by De Natura Sonorum and use new techniques such as those featured in UPIC. La Création du Monde is a vast saga clocking in at 73 minutes, comprising 3 pieces, and was awarded a Victoire de la Musique in 1989. The Plain-temps series also makes up a trilogy:- Le Présent composé in 1991, Entre-temps in 1992, and Plain temps in 1993.

Then, from 1996 onwards, Parmegiani pursued short form compositions as a more suitable approach to his work. The possibilities brought about by developments in music technology allowed him to revisit certain familiar themes:- Sonares (1996) is concerned with the meeting and mixing of natural and synthetic sounds; in La mémoire des sons (2000-2001), “the sounds of the past contribute to the composition of the present”; and Rêveries (2007), his last piece, guides the listener through a 14-minute tour of his past works.

Throughout this period, Parmegiani continued to work within various different musical genres. Film music includes V. Borowczyck's Dr. Jekyll et les femmes; for television he wrote for four episodes of Mario Ruspoli's L'Art au Monde des ténèbres (1982); he wrote the text as well as the music for the radio show E pericoloso sporgersi; for ballet with Vittorio Biagi's Rouge-mort and the Opéra de Nice; and last but not least, his musical happenings such as Démons et des mots with the haute-contre singer and actor Frank Royon Le Mée...

This career path is outlined in more detail in Eveylne Gayou's interview with Bernard Parmegiani, extracts of which can be found on the site under the title Mots de l'immédiat (in Portaits Polychromes, BP, INA/GRM).

Parmegiani's work has received many awards :

- 1976 Prix Italia Laureate

- 1979 Disque Français Grand Prix

- 1981 Prix de la Sacem

- 1990 5th Victoires de la Musique – Contemporary Music Prize

- 1991 Bourges International Competition – Prix Magister

- 1993 Ars Electronica - Linz (Autriche), Grand Prix Golden Nika

- 2006 Quartz électronique – Pierre Schaeffer Memorial Prize

- 2010 Prix Charles Cros (Prize of the President of the Republic) for the 12-disk INA/GRM boxset.