Bernard's Studios

The Man of Sound

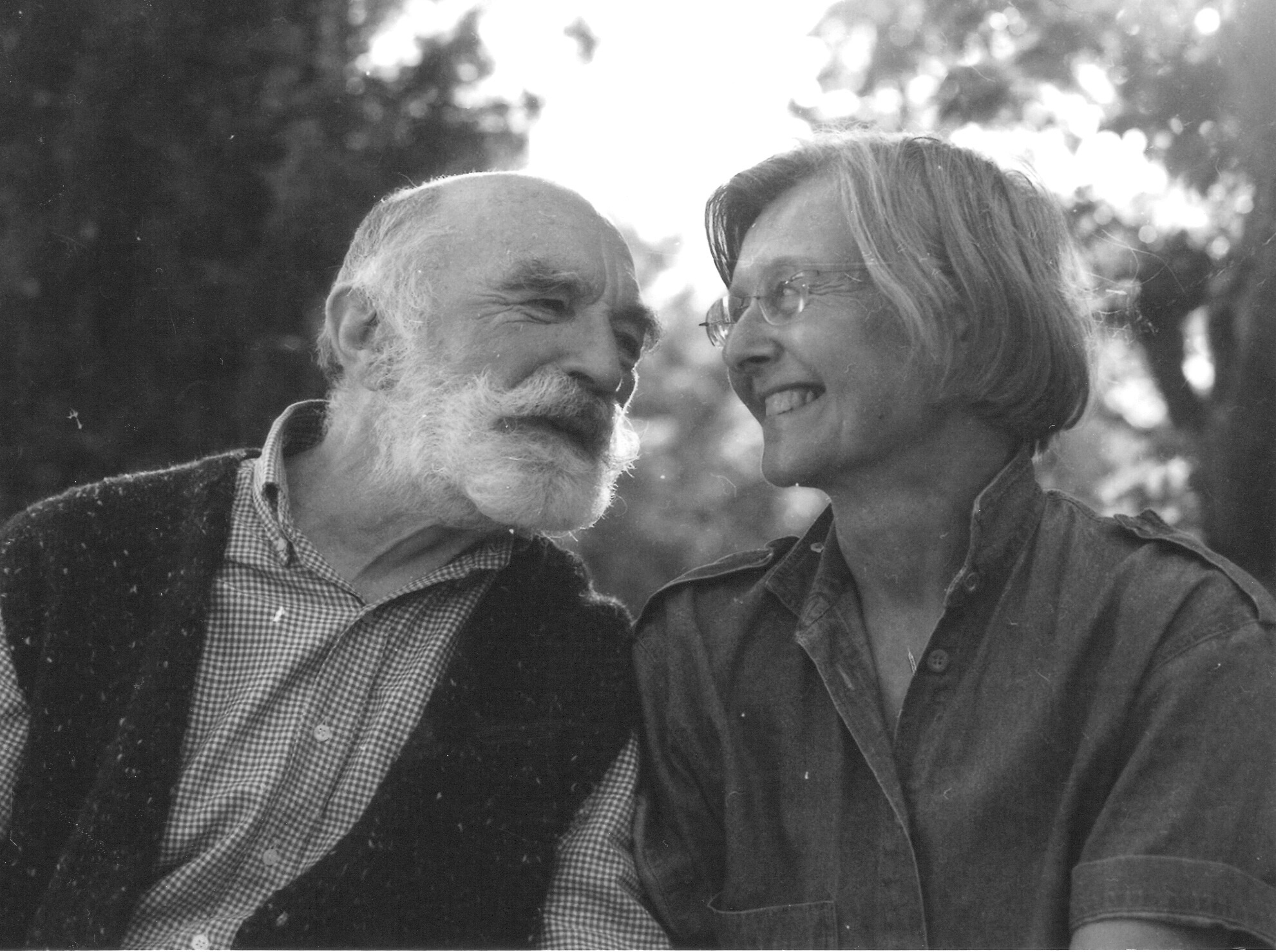

Claude-Anne Bezombes Parmegiani

Bernard always enjoyed an organic relationship with “his studio”, or rather the place which first and foremost he would use as a studio.

When I first met him at the GRM in May 1964, when Pierre Schaeffer came to listen to the newly-completed Violostries, he already owned an enormous tape-player which took up a large amount of space in his tiny home on the Rue de Savoie. And later when Bernard would cross the two arms of the Seine to move into my little Parisian apartment, finding space for this cumbersome companion posed a problem. It was part of his tireless daily writing process, and hearing “his sounds” couldn't be done without it. What I didn't realize at the time was how much this machine was, over the years, going find itself many more companions of its own...

So we tried out the various places that might accommodate the tape player in question:- in the kitchen? Too small. The bathroom? Too humid. Hallway? Too narrow. Living room? Too many two- and four-legged flatmates there already. Only the bedroom remained... but where could the Studer go in a room already filled with a double bed and marble fireplace? Piece of cake – next to the bed, the composer, naturally inclined to DIY, put up a board which folded out over the bed during the day and which was folded back up at night so we could sleep. It would however come about, when I was pregnant, that I felt the need – highly inappropriate! - to lie down in the afternoon. I therefore had to slide underneath the folding board, whose capacity to hold up the heavy tape player I always doubted a little, while Bernard would continue to listen to and edit the sounds he was working on at the time without noticing. Such were the circumstances in which were born, simultaneously in 1966, our son Emmanuel and Capture Ephémère !, cradled by one another.

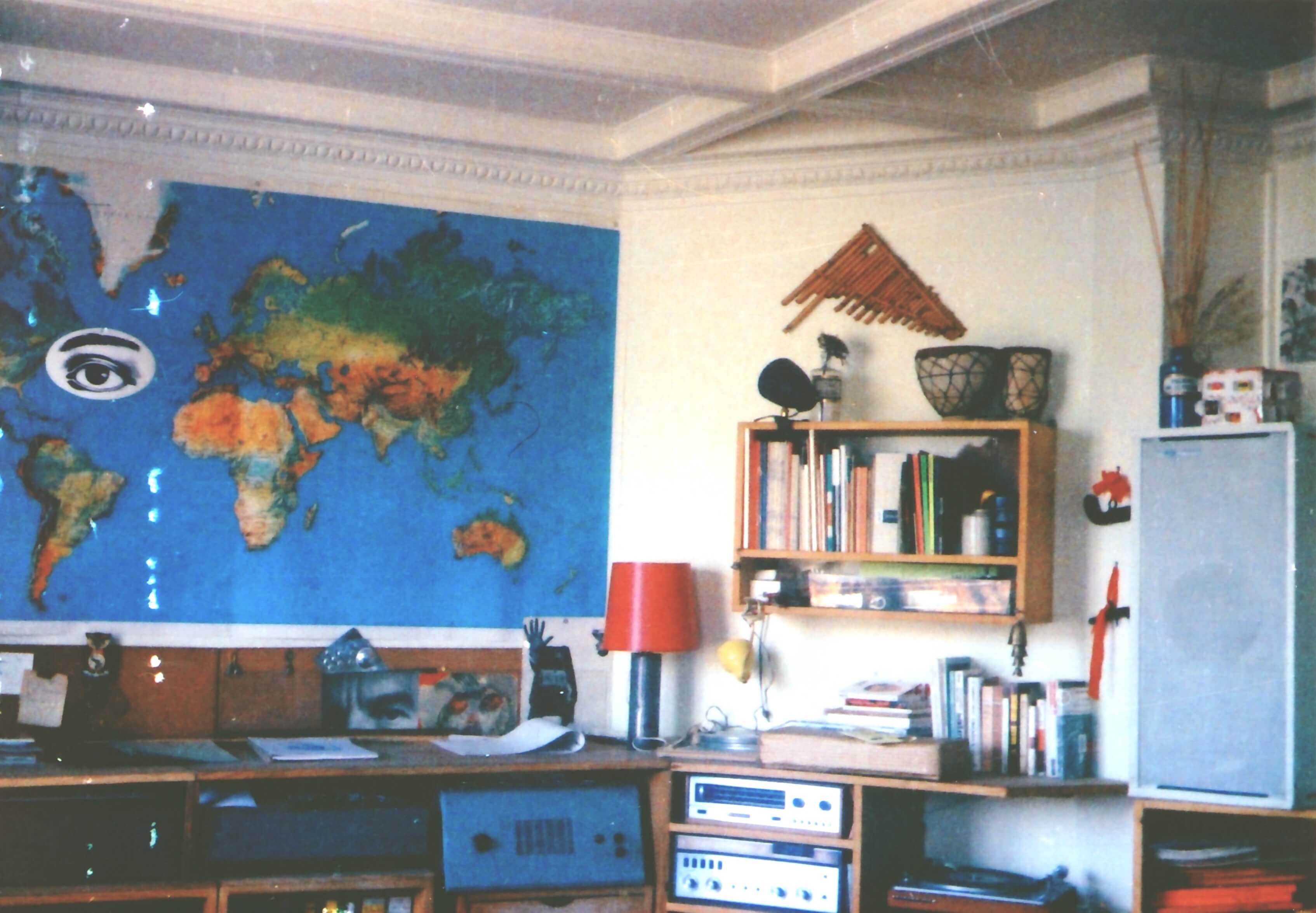

Of course, things couldn't remain that way forever – the children were growing up, and the machines too! We were in need of an apartment suitable for our new situation, that is, something with an extra bedroom and a separate studio. In 1969, we indeed found somewhere spacious but still insufficient given Bernard's ever-growing arsenal. Soon enough, what was supposed to be the “parents' bedroom” was converted into “the music room”, with the marriage bed slotted behind a sliding partition in the living room!

Because being a composer doesn't mean not being able to work out how best to use one's working space and family space. On the Rue Ballu, my desk was up against the studio wall, so during several long months I heard tirelessly repeated sounds which were to become the elements of De Natura Sonorum. I was getting worried – would he finish in time? Gradually, these sounds – cut up, transformed, remixed, and reorganized – became music. I understood how an electroacoustic composer worked, tearing the material out of its banality at the root, assembling it sound by sound until it's given a form and is composed into a musical work.

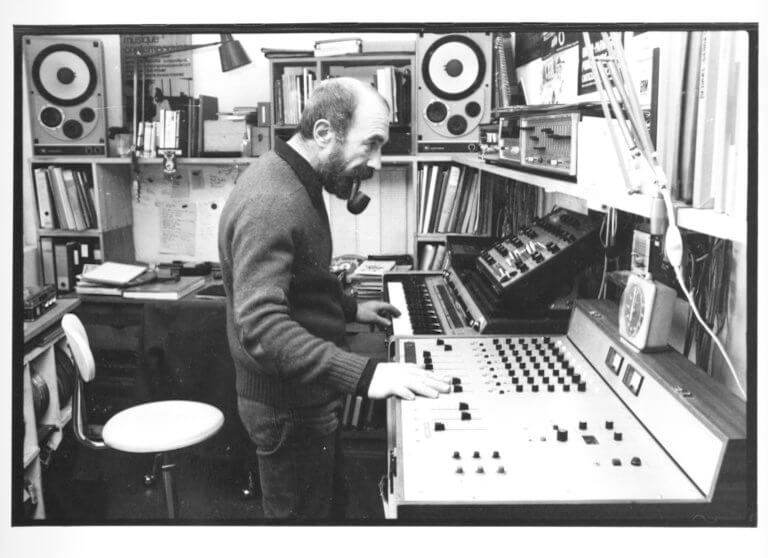

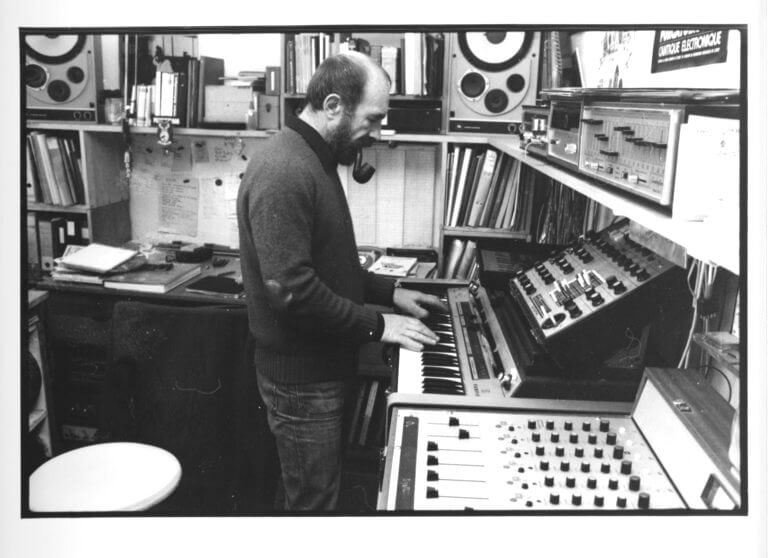

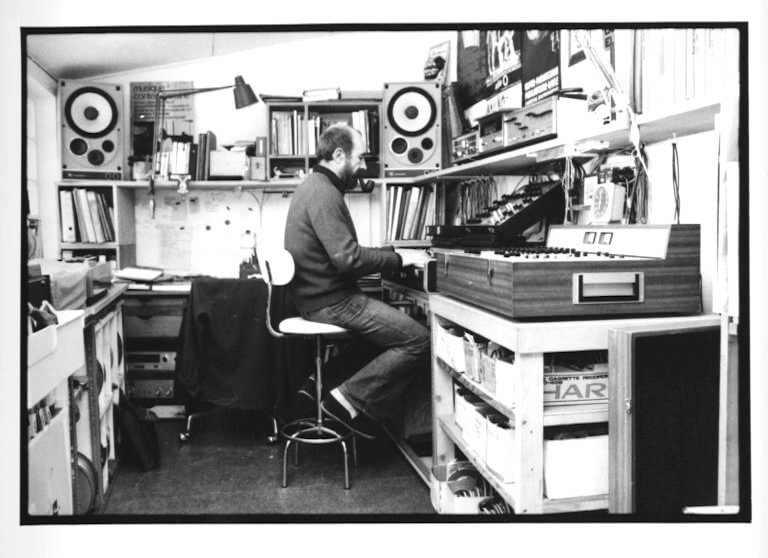

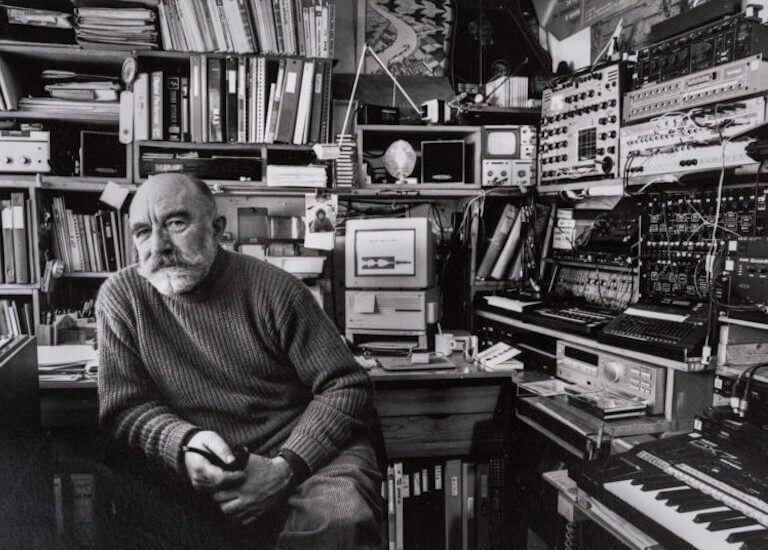

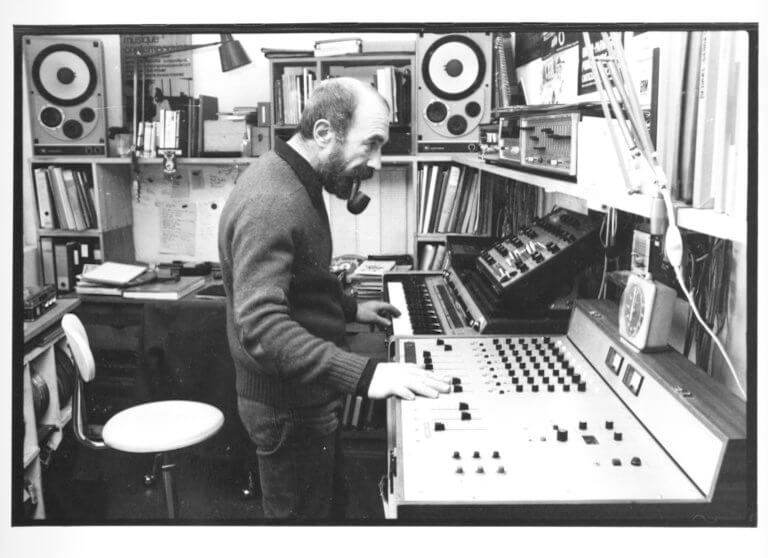

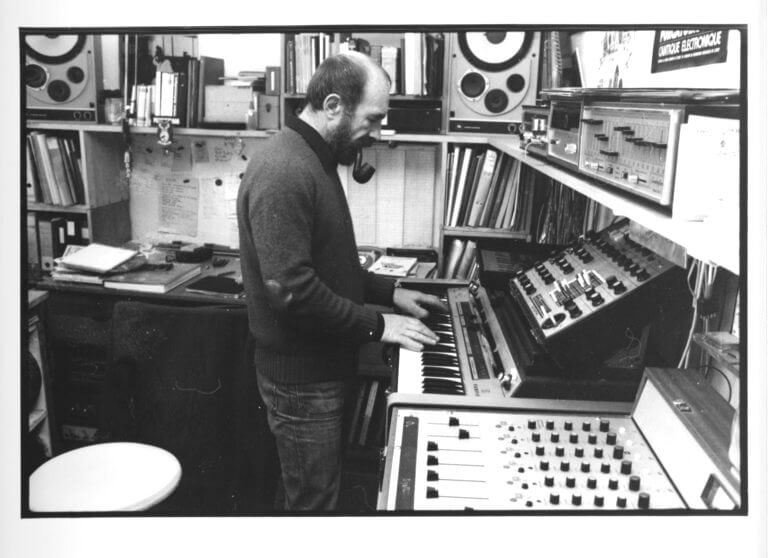

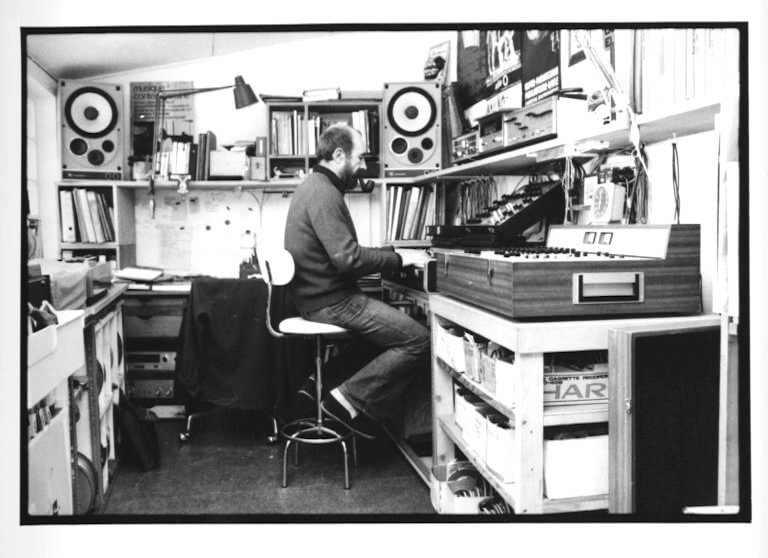

This unceasing, demanding, daily toil prolonged or prepared that which was then carried out in the handsomely equipped studios of the GRM. Wrestling with the various synthesizers, the TR-808, the famous Farfisa organ, the Clavinet, etc.; all the programs from the '70's and the beginning of the '80's; the recording equipment:- it engulfed and transformed our family life wherein domestic objects were given a second life as sonic objects. For instance, the first movement of De Natura Sonorum, Incidences/résonnances, was written using sounds made with a large metal salad bowl that my mother had given us for Christmas. The grating sound at the beginning of Présent Composé comes from the shutters at our house at Villebon that Bernard closed every night. But the liberty which the composer enjoyed so much in his own studio came with the constraints imposed by the modesty of his equipment. The huge difference between the sumptuousness of the GRM's equipment and the restrictions within what was starting to be called a “home studio” had surely forced upon him a sense of rigor which put his fierce inventiveness and imagination for sounds to the test as sources of never-ending renewal. Parmegiani was the first and for a long time the only one at the GRM to have his own equipment so that he could compose at home. Even today, when I take stock of the number of hours of music that he made during this period which he himself had baptised the “Era of the Scissors”, the tyrannical necessity of a studio at home is glaringly obvious.

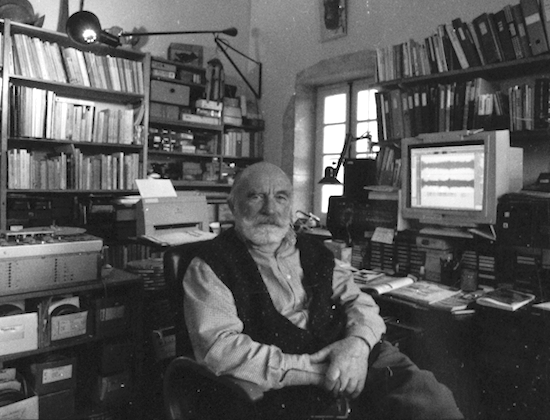

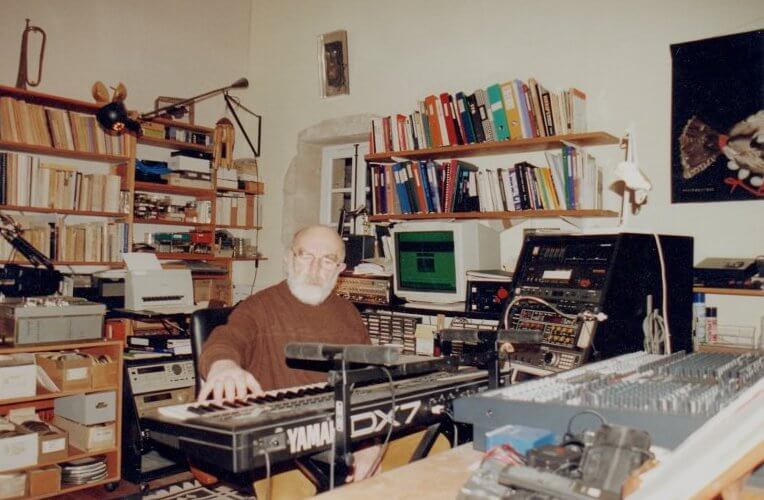

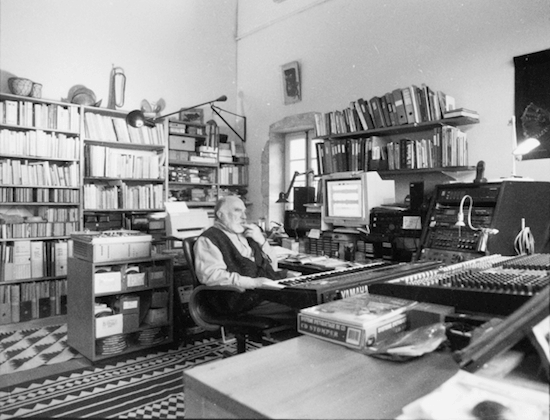

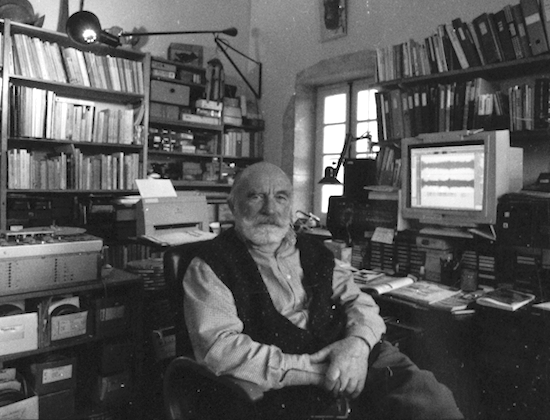

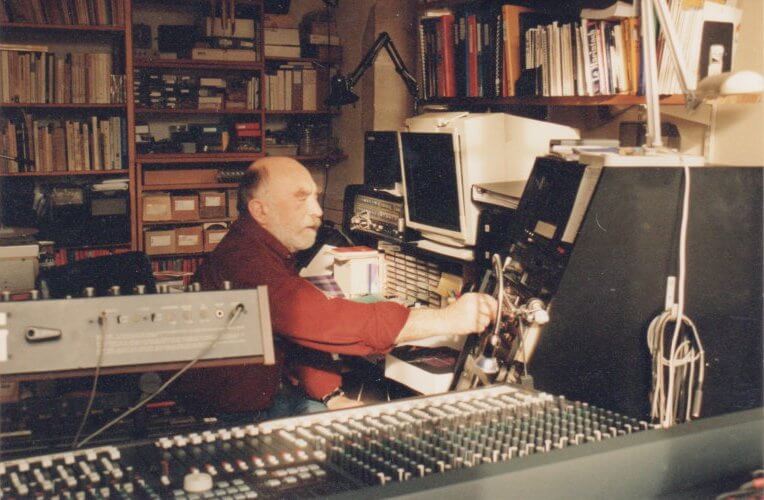

Bernard's second studio (1976-1997), the one in which he worked the longest (for more than 20 years), was in Villebon-sur-Yvette. This is where he made the leap from the Age of Scissors to the Age of the Mouse. Which is to say that the amount of equipment multiplied substantially, since the new possibilities offered by the M.I.D.I. system (the programs that were part of digitization), were of the greatest interest to him. The change of equipment required a distinct working method – testing these new instruments' resources began taking up more and more time, and composing took up less and less. The studio was an oblong shape, not very well soundproofed, situated at the bottom of the garden. But for Bernard it was one of his favourite places to be.

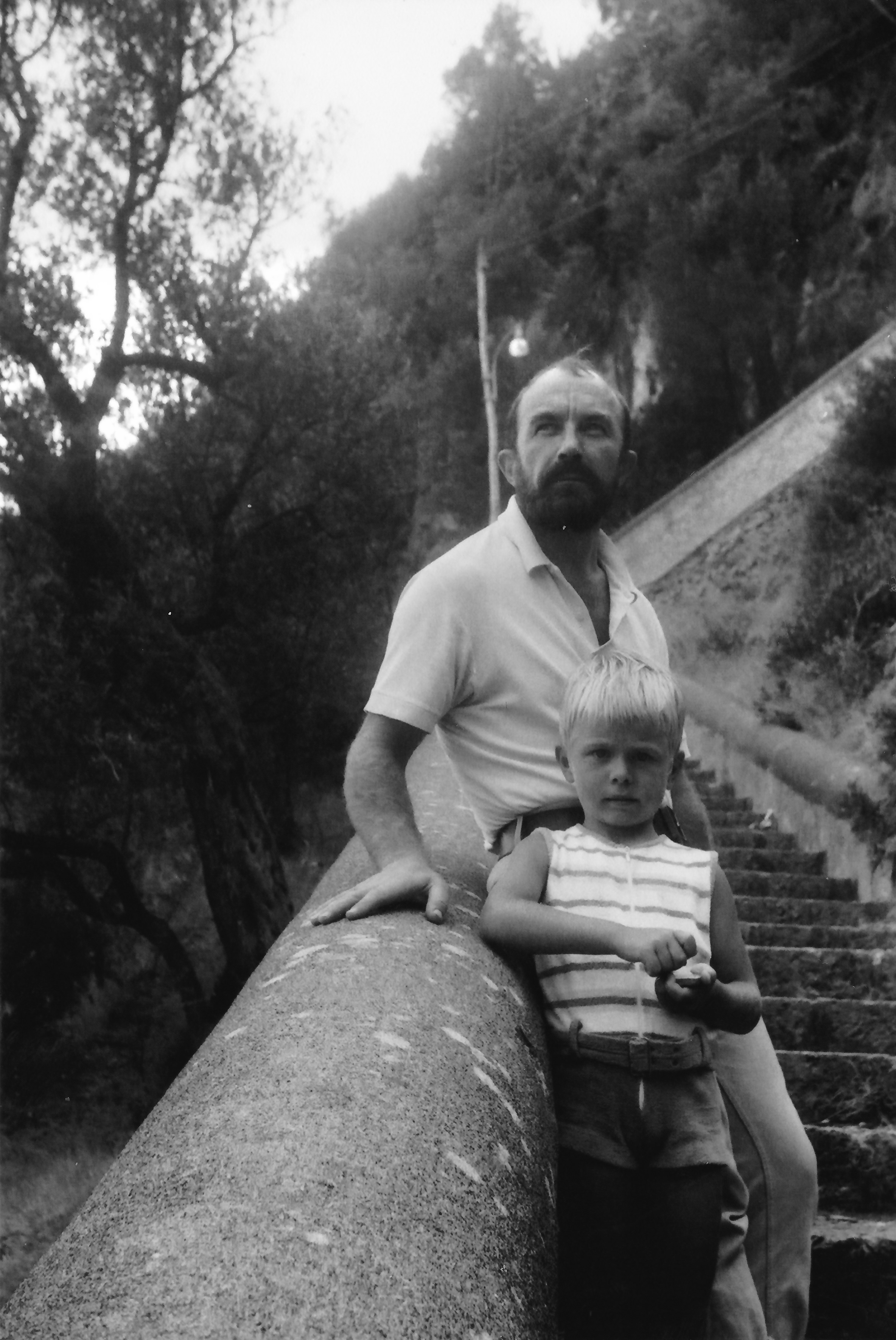

Even when the time came for holidays, this studio wasn't forgotten. We usually left for Italy, towards Amalfi (1,700km away!) with the children and tape-player in the car. As soon as we arrived, a ritual was begun:- in the morning, Bernard worked. He listened, catalogued and sometimes edited his sounds before the bay's sublime landscape while we went down to the beach. Then he joined us for lunch, teaching his son how to swim, shaking himself off in the sea because he was an excellent swimmer. For him to accept cutting the umbilical cord connecting him to his studio, there had to be at least a trip to some far-off land, somewhere which piqued his curiosity. And even then... most of the time, they ended up becoming business trips which meant hours of rehearsal.

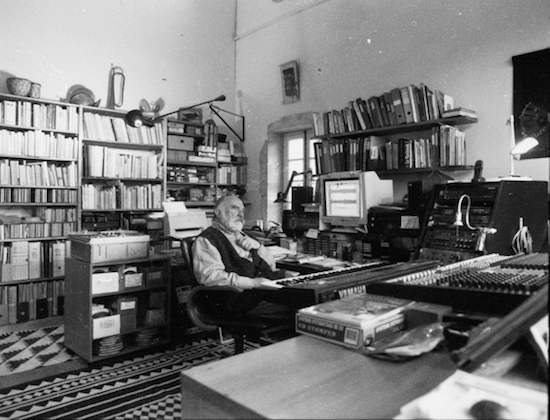

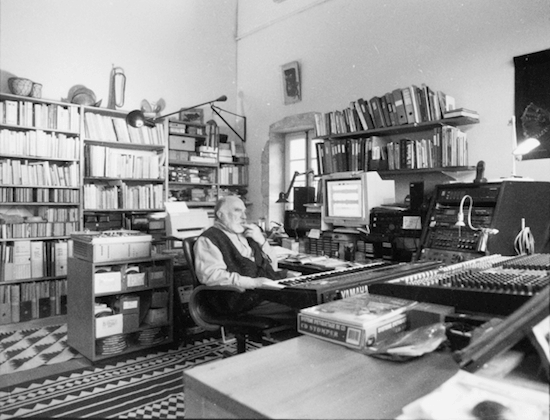

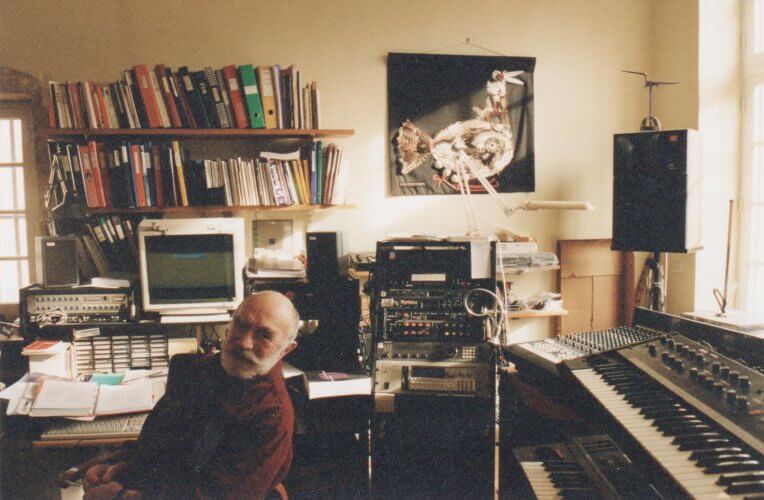

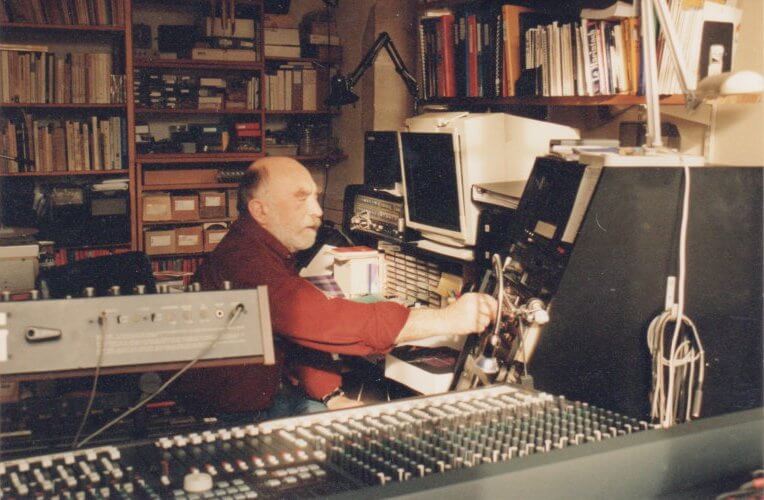

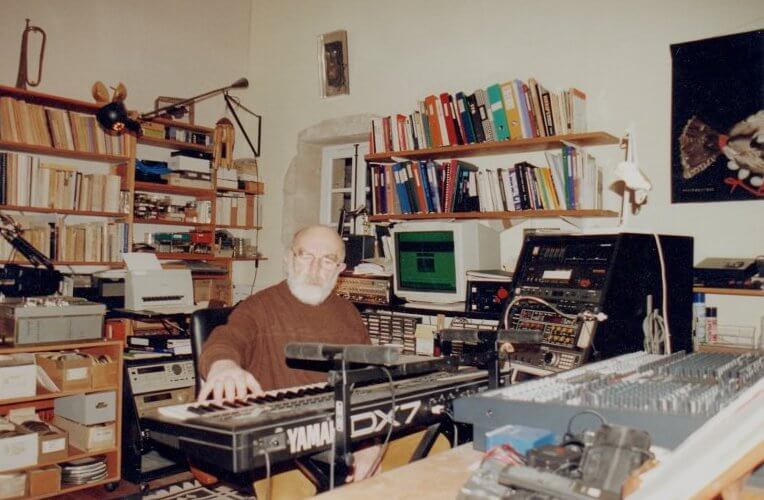

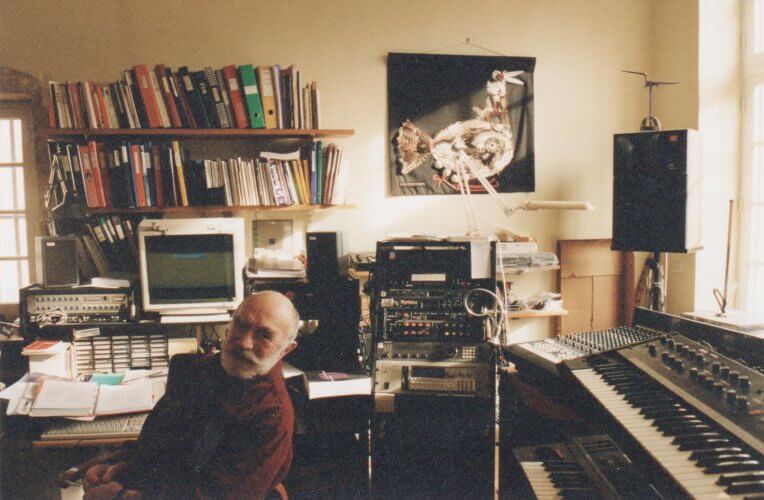

The third studio was in St. Remy de Provence (1997-2005). The view wasn't altogether as stunning as the one on the bay of Amalfi, but the large window nonetheless looked onto the Alpilles. The room was immense and bright, but... the acoustic was not great, and in summer it was oppressively hot. The Provençal studio, far from the commotion of the outside world, was without doubt the one he loved the most – a love shared by Musette, our little cat, who made herself at home here and slept in front of the window on the protective cover of one of the synthesizers.

The last studio was the one on Rue du Château in Paris. Bernard had everything set up the same way as in St Remy, because more than anything else he needed his surroundings to stay the same. He didn't compose very much in this studio, despite Marco Marini's kind assistance. He was coming back around to his first loves – he made photomontages and little objects which, though unfortunately short-lived, were full of an imagination which showed his taste for comic fabrications and shapes in transformation. He listened to music, especially by other composers. This place had a contemplative, intimate, almost magical atmosphere. For a long time after he'd stopped composing there he'd still go twice a day. He was surrounded by his books, his tapes, his sounds and his music-making machines.

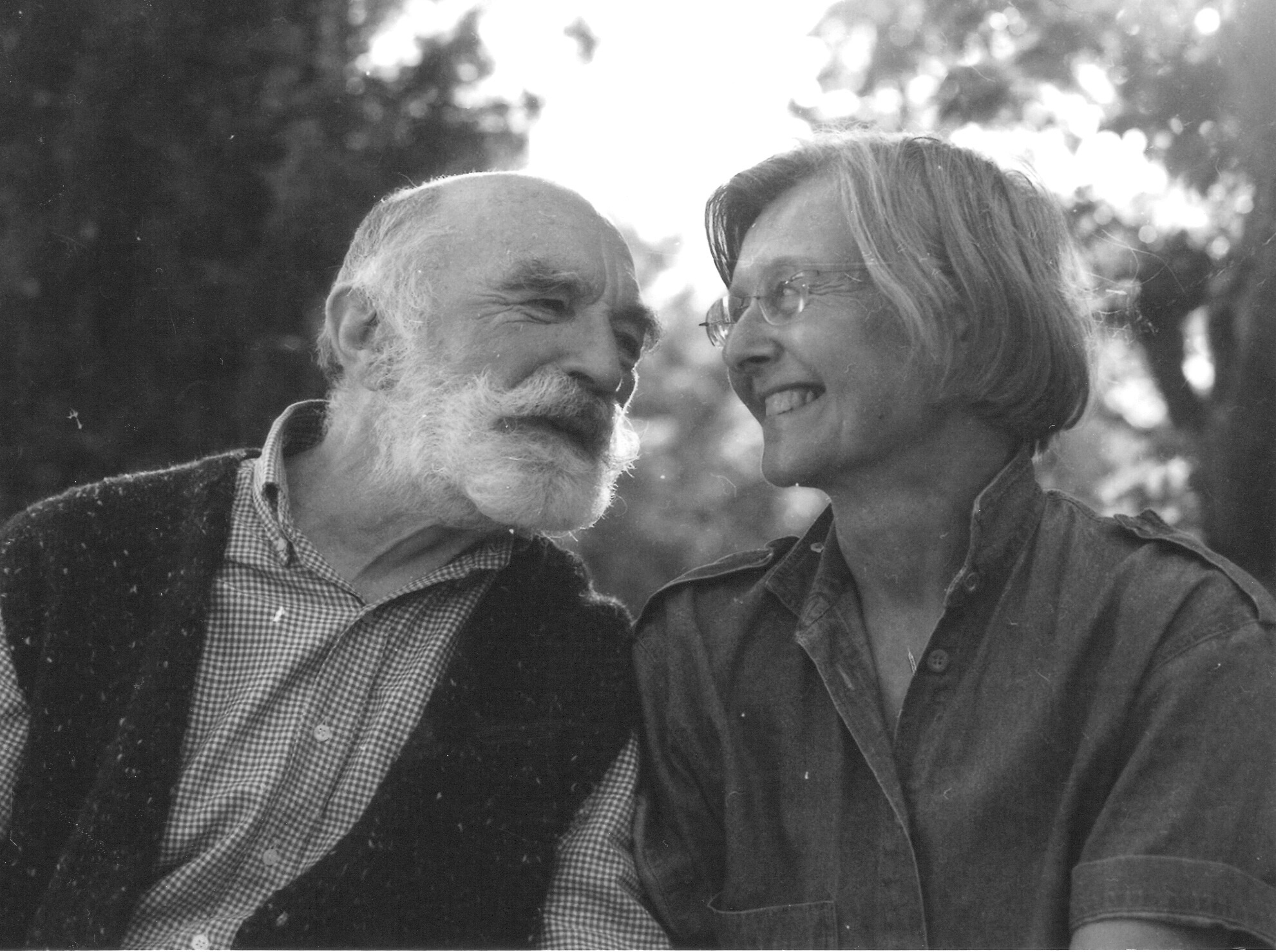

“And then...”? What if there's an answer to that great mystery which is death, and this “and then” exists? I can easily imagine that Bernard will have worked out how to get his hands on some celestial tape-player to work on “unheard of” sounds with.

Grignan may 2016

Bernard's Studios

The Man of Sound

Claude-Anne Bezombes Parmegiani

Bernard always enjoyed an organic relationship with “his studio”, or rather the place which first and foremost he would use as a studio.

When I first met him at the GRM in May 1964, when Pierre Schaeffer came to listen to the newly-completed Violostries, he already owned an enormous tape-player which took up a large amount of space in his tiny home on the Rue de Savoie. And later when Bernard would cross the two arms of the Seine to move into my little Parisian apartment, finding space for this cumbersome companion posed a problem. It was part of his tireless daily writing process, and hearing “his sounds” couldn't be done without it. What I didn't realize at the time was how much this machine was, over the years, going find itself many more companions of its own...

So we tried out the various places that might accommodate the tape player in question:- in the kitchen? Too small. The bathroom? Too humid. Hallway? Too narrow. Living room? Too many two- and four-legged flatmates there already. Only the bedroom remained... but where could the Studer go in a room already filled with a double bed and marble fireplace? Piece of cake – next to the bed, the composer, naturally inclined to DIY, put up a board which folded out over the bed during the day and which was folded back up at night so we could sleep. It would however come about, when I was pregnant, that I felt the need – highly inappropriate! - to lie down in the afternoon. I therefore had to slide underneath the folding board, whose capacity to hold up the heavy tape player I always doubted a little, while Bernard would continue to listen to and edit the sounds he was working on at the time without noticing. Such were the circumstances in which were born, simultaneously in 1966, our son Emmanuel and Capture Ephémère !, cradled by one another.

Of course, things couldn't remain that way forever – the children were growing up, and the machines too! We were in need of an apartment suitable for our new situation, that is, something with an extra bedroom and a separate studio. In 1969, we indeed found somewhere spacious but still insufficient given Bernard's ever-growing arsenal. Soon enough, what was supposed to be the “parents' bedroom” was converted into “the music room”, with the marriage bed slotted behind a sliding partition in the living room!

Because being a composer doesn't mean not being able to work out how best to use one's working space and family space. On the Rue Ballu, my desk was up against the studio wall, so during several long months I heard tirelessly repeated sounds which were to become the elements of De Natura Sonorum. I was getting worried – would he finish in time? Gradually, these sounds – cut up, transformed, remixed, and reorganized – became music. I understood how an electroacoustic composer worked, tearing the material out of its banality at the root, assembling it sound by sound until it's given a form and is composed into a musical work.

This unceasing, demanding, daily toil prolonged or prepared that which was then carried out in the handsomely equipped studios of the GRM. Wrestling with the various synthesizers, the TR-808, the famous Farfisa organ, the Clavinet, etc.; all the programs from the '70's and the beginning of the '80's; the recording equipment:- it engulfed and transformed our family life wherein domestic objects were given a second life as sonic objects. For instance, the first movement of De Natura Sonorum, Incidences/résonnances, was written using sounds made with a large metal salad bowl that my mother had given us for Christmas. The grating sound at the beginning of Présent Composé comes from the shutters at our house at Villebon that Bernard closed every night. But the liberty which the composer enjoyed so much in his own studio came with the constraints imposed by the modesty of his equipment. The huge difference between the sumptuousness of the GRM's equipment and the restrictions within what was starting to be called a “home studio” had surely forced upon him a sense of rigor which put his fierce inventiveness and imagination for sounds to the test as sources of never-ending renewal. Parmegiani was the first and for a long time the only one at the GRM to have his own equipment so that he could compose at home. Even today, when I take stock of the number of hours of music that he made during this period which he himself had baptised the “Era of the Scissors”, the tyrannical necessity of a studio at home is glaringly obvious.

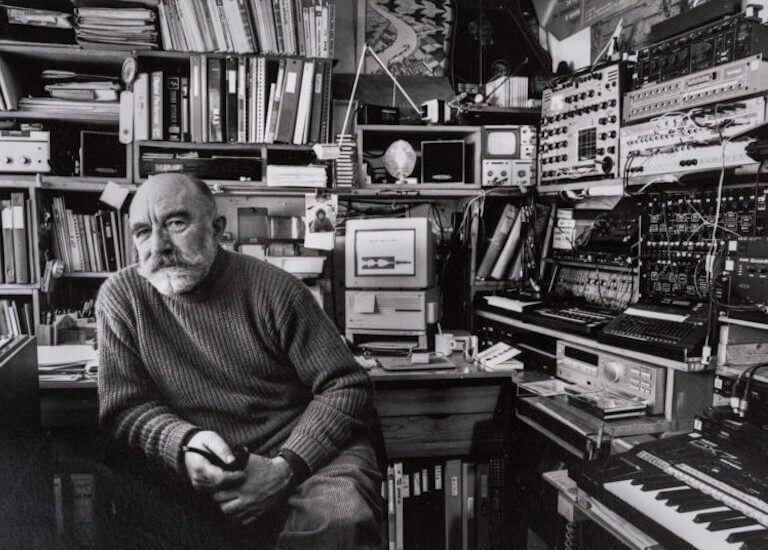

Bernard's second studio (1976-1997), the one in which he worked the longest (for more than 20 years), was in Villebon-sur-Yvette. This is where he made the leap from the Age of Scissors to the Age of the Mouse. Which is to say that the amount of equipment multiplied substantially, since the new possibilities offered by the M.I.D.I. system (the programs that were part of digitization), were of the greatest interest to him. The change of equipment required a distinct working method – testing these new instruments' resources began taking up more and more time, and composing took up less and less. The studio was an oblong shape, not very well soundproofed, situated at the bottom of the garden. But for Bernard it was one of his favourite places to be.

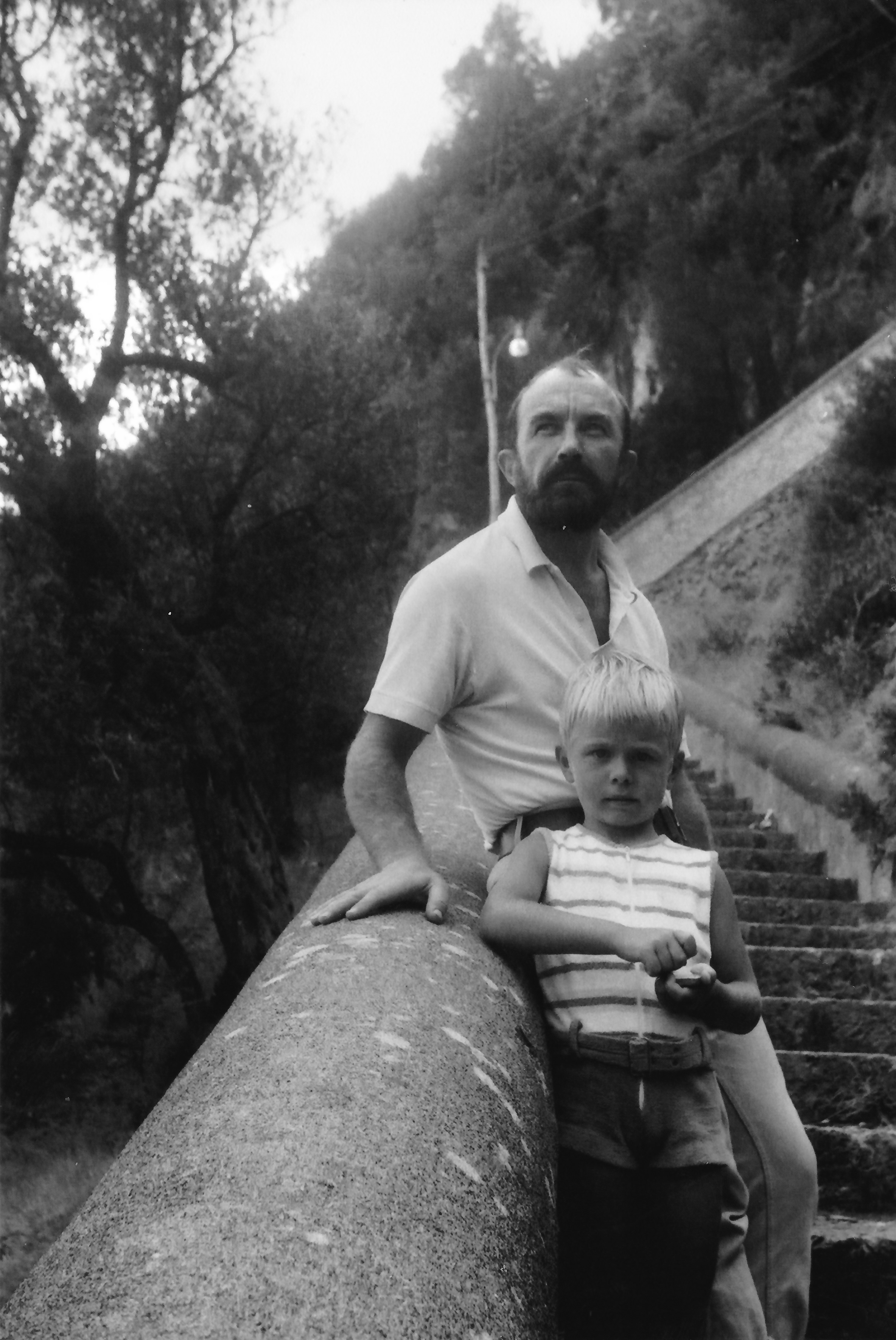

Even when the time came for holidays, this studio wasn't forgotten. We usually left for Italy, towards Amalfi (1,700km away!) with the children and tape-player in the car. As soon as we arrived, a ritual was begun:- in the morning, Bernard worked. He listened, catalogued and sometimes edited his sounds before the bay's sublime landscape while we went down to the beach. Then he joined us for lunch, teaching his son how to swim, shaking himself off in the sea because he was an excellent swimmer. For him to accept cutting the umbilical cord connecting him to his studio, there had to be at least a trip to some far-off land, somewhere which piqued his curiosity. And even then... most of the time, they ended up becoming business trips which meant hours of rehearsal.

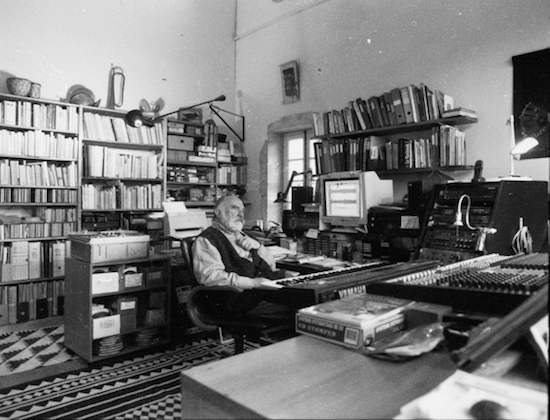

The third studio was in St. Remy de Provence (1997-2005). The view wasn't altogether as stunning as the one on the bay of Amalfi, but the large window nonetheless looked onto the Alpilles. The room was immense and bright, but... the acoustic was not great, and in summer it was oppressively hot. The Provençal studio, far from the commotion of the outside world, was without doubt the one he loved the most – a love shared by Musette, our little cat, who made herself at home here and slept in front of the window on the protective cover of one of the synthesizers.

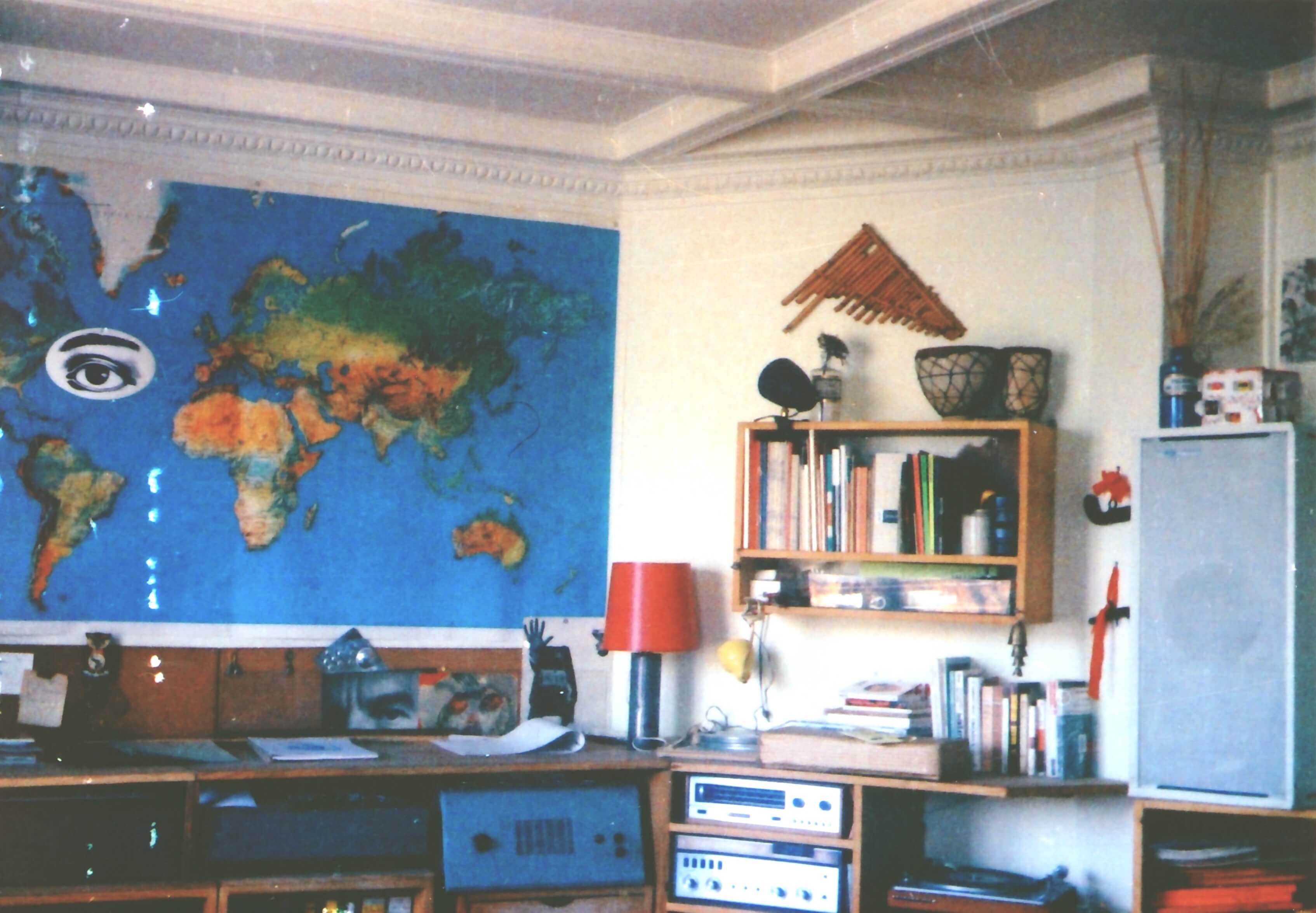

The last studio was the one on Rue du Château in Paris. Bernard had everything set up the same way as in St Remy, because more than anything else he needed his surroundings to stay the same. He didn't compose very much in this studio, despite Marco Marini's kind assistance. He was coming back around to his first loves – he made photomontages and little objects which, though unfortunately short-lived, were full of an imagination which showed his taste for comic fabrications and shapes in transformation. He listened to music, especially by other composers. This place had a contemplative, intimate, almost magical atmosphere. For a long time after he'd stopped composing there he'd still go twice a day. He was surrounded by his books, his tapes, his sounds and his music-making machines.

“And then...”? What if there's an answer to that great mystery which is death, and this “and then” exists? I can easily imagine that Bernard will have worked out how to get his hands on some celestial tape-player to work on “unheard of” sounds with.

Grignan may 2016