Mots de l’immédiat

Extract from a 2002 interview between Bernard Parmegiani and Évelyne Gayou, published in extenso in Portraits Polychromes Bernard Parmegiani (Ina, 2002-2007).

Évelyne Gayou :

This is what I know about you so far: you were born in 1927 and you spent your childhood between two pianos – your mother's and your father-in-law's, both piano teachers. So being young and without much choice given the circumstances, you studied this instrument.

Bernard Parmegiani :

I was in some sense “stuck between two pianos”, and this is actually true since there was on one side of my bedroom my father-in-law's room, the virtuoso pianist who taught the best and most advanced students from the Conservatoire, and on the other side was my mother who went through “do-ré-mi-fa-sol-la-si-do” with the little children to whom she taught Scarlatti. She's the one who made me work for many years. I would occasionally have lessons with my father-in-law but it was rare because he was very busy or on tour. But when I worked on the piano I spent a lot of time improvising based on what I'd been hearing. I tried to do Ravel, Debussy, Beethoven, or Mozart and sometimes even some Parmegiani […]. I wouldn't have hated becoming a pianist, but it didn't take off.

Afterwards, you went off to do your military service at the Army Cinema Service for three years, and then you went into radio.

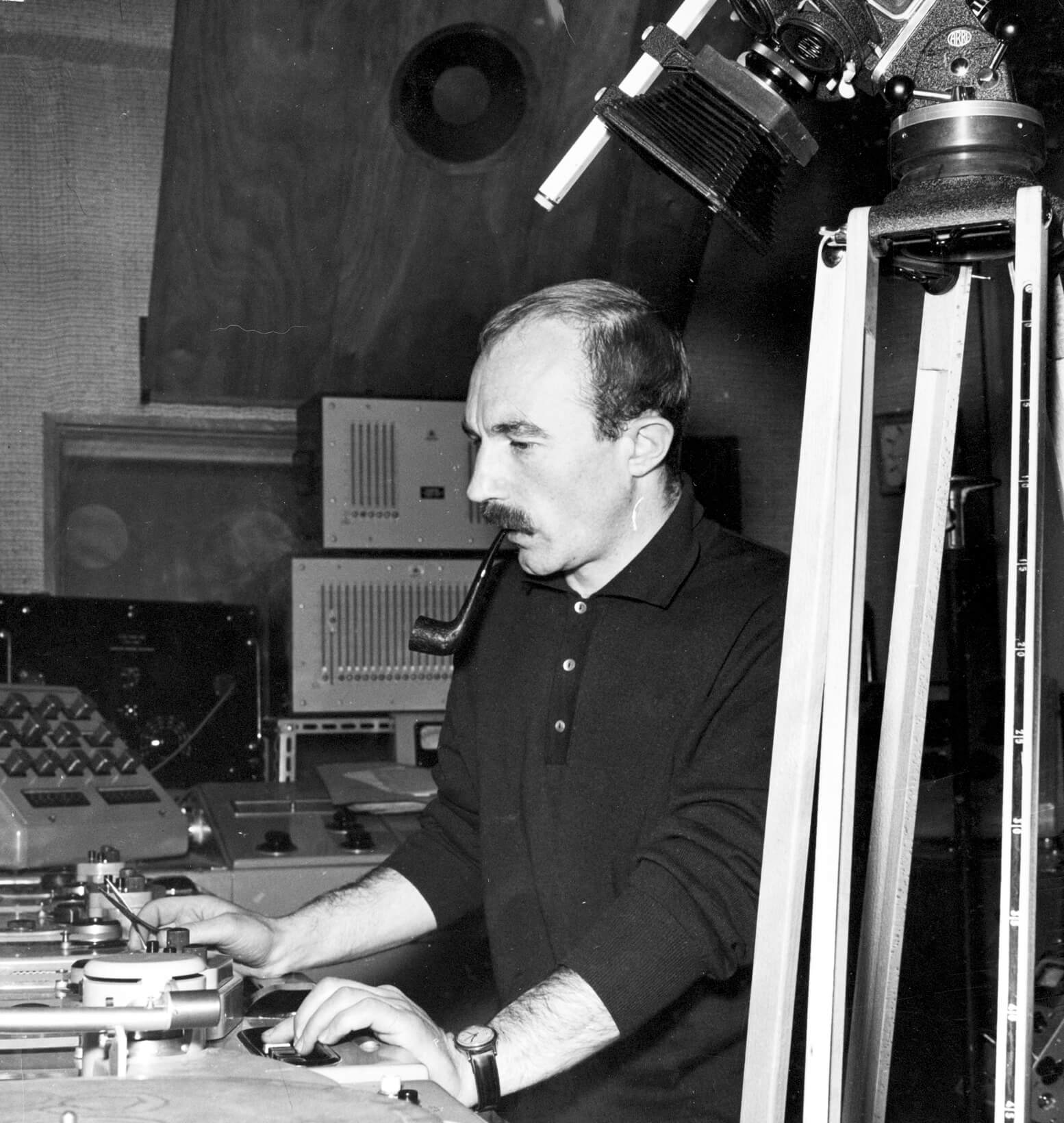

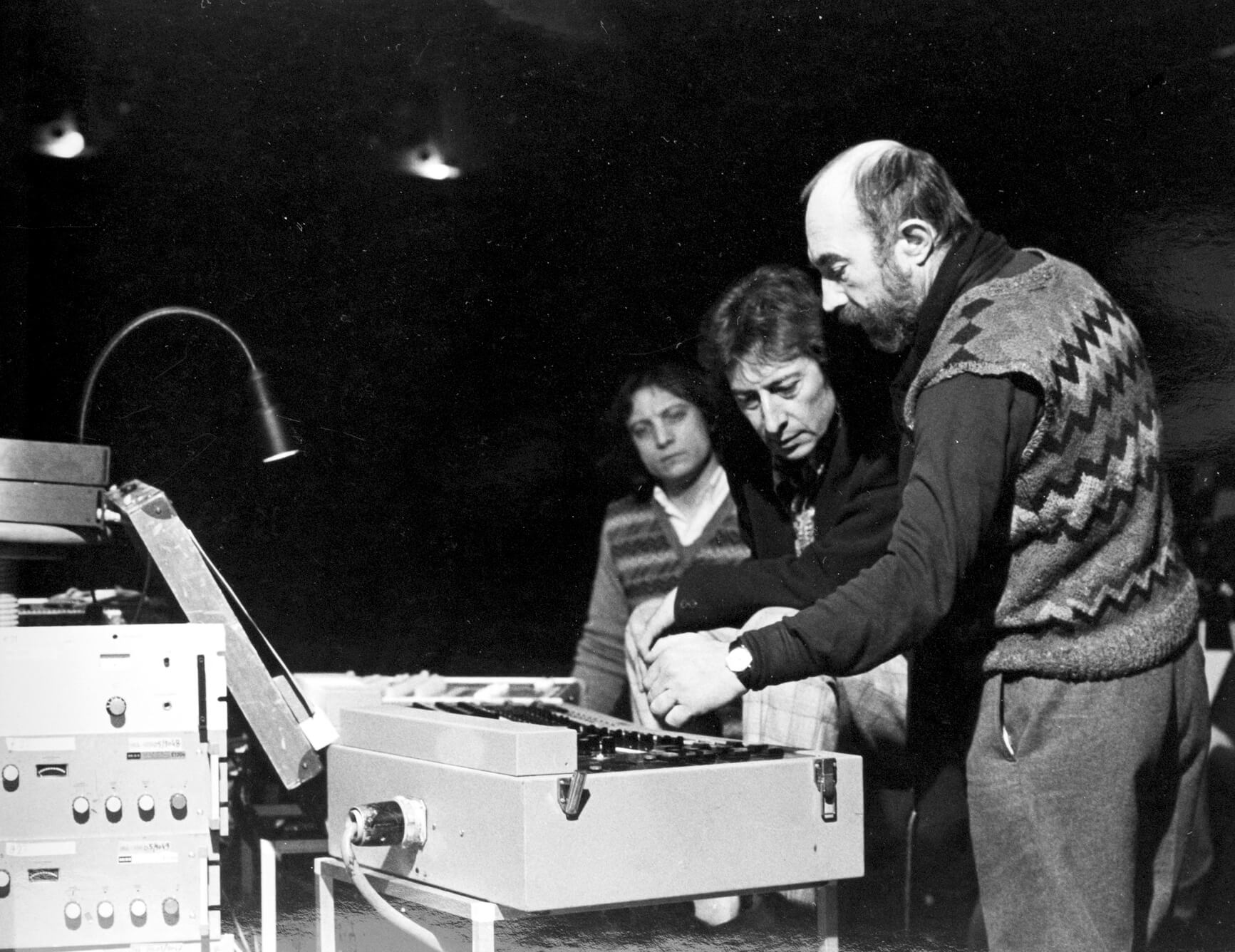

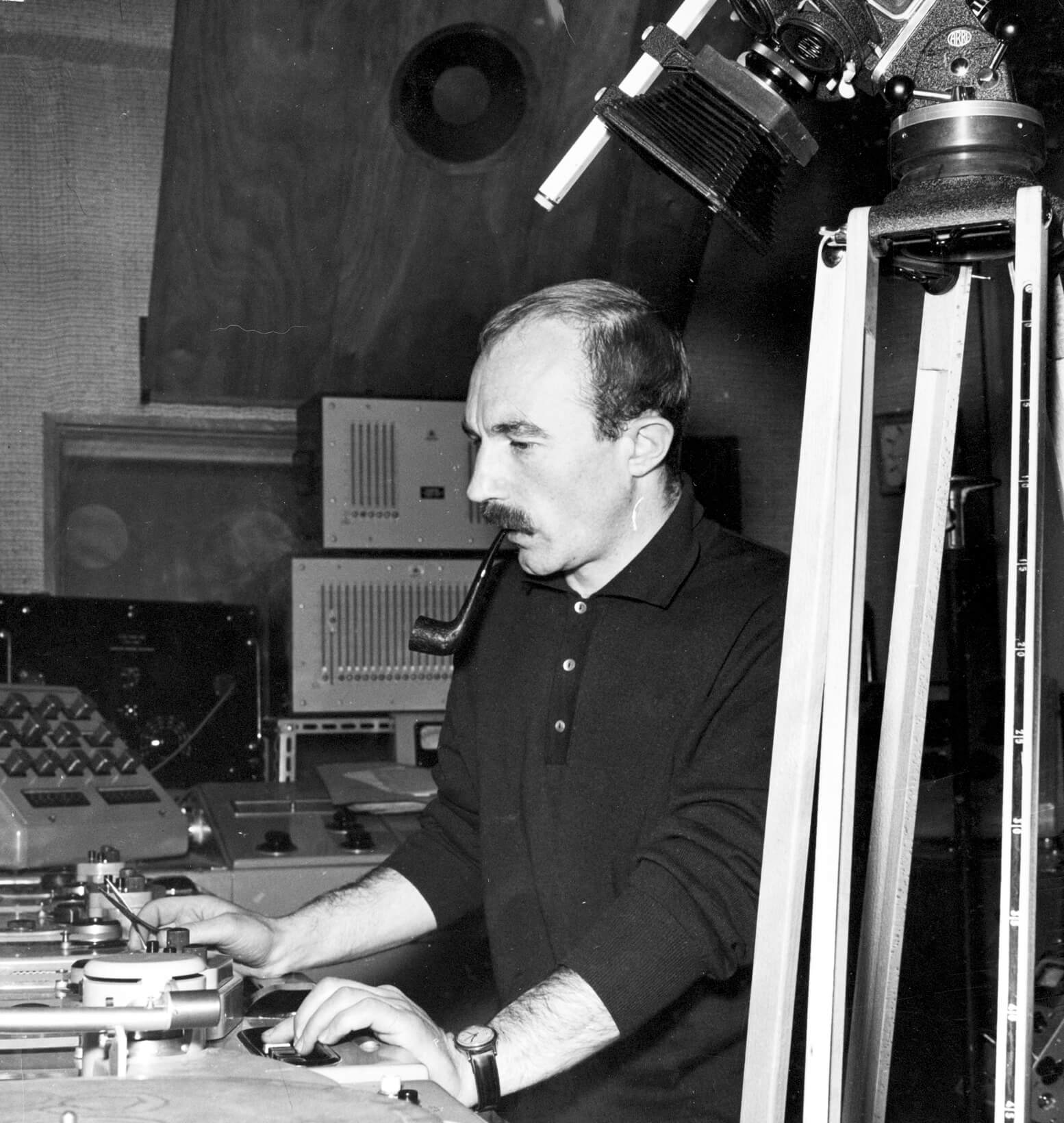

Before going into radio I'd prepared for a competition for radio producers. Unfortunately I came 7 out of 100... And there were only 5 places at Paris while the others were sent outside of the capital. Since I didn't want to leave Paris I had to abandon producing and I got into radio […] as an assistant operator for a year and a half. There, I was taught techniques for recording at the radio which rounded off the Army Service Cinema training in recording sound for film. After that I went into television where I would stay for three years. At the beginning I was a sound engineer, that is, boom operator, for TV dramas – holding the boom up, underneath the projectors. It was quite gruelling work. Then, eventually, I got to the console. And when you become team leader, you get to fiddle with the knobs.

During this time I would also visit the Research Centre for Radio and Television at the Club d'Essai. I went to conferences on broadcasting, sound recording, radio esthetics, etc. and there I met André Almuro. Since I had begun to make sound montages on tape for animations and radio adverts, he invited me to come work at the Maison des Lettres to make what they were calling “experimental” music. I did that on the sly when the studios were empty.

André Almuro was writing a piece which was called, would you believe it, De Natura Rerum, after Lucretius. So it wasn't far to go from De Natura Rerum to De Natura Sonorum, even if there are sixteen years between them and they share neither the same aims nor musical forms.

Anyway, one day, Schaeffer came to see us in our little studio to listen to our work which he glowingly praised. After that, we analyzed La Symphonie pour un homme seul together. Following this brief encounter, Schaeffer invited Almuro to join the Research Service in the capacity of a composer, and Almuro asked that I be able to come with him as a sound engineer. But in order for that to happen, I had to leave television. Schaeffer himself, a few months later, literally tore me away from my post as sound engineer for TV, and at the Groupe de Recherches Musicales I simultaneously became a fully-fledged sound engineer and assistant editor. I started out helping Xenakis, Ferrari, and then others. I knew these people by name before joining the GRM because since 1951 I'd been listening a lot to the Club d'Essai (at the Univeristy of Paris) which was directed by the poet Jean Tardieu and which housed the GRM studios. I listened to the musique concrète concerts every sunday and of course I'd heard pieces by Luc Ferrari, Pierre Schaeffer, Pierre Henry – those were the three main ones – and François-Bernard Mâche came along a little later.

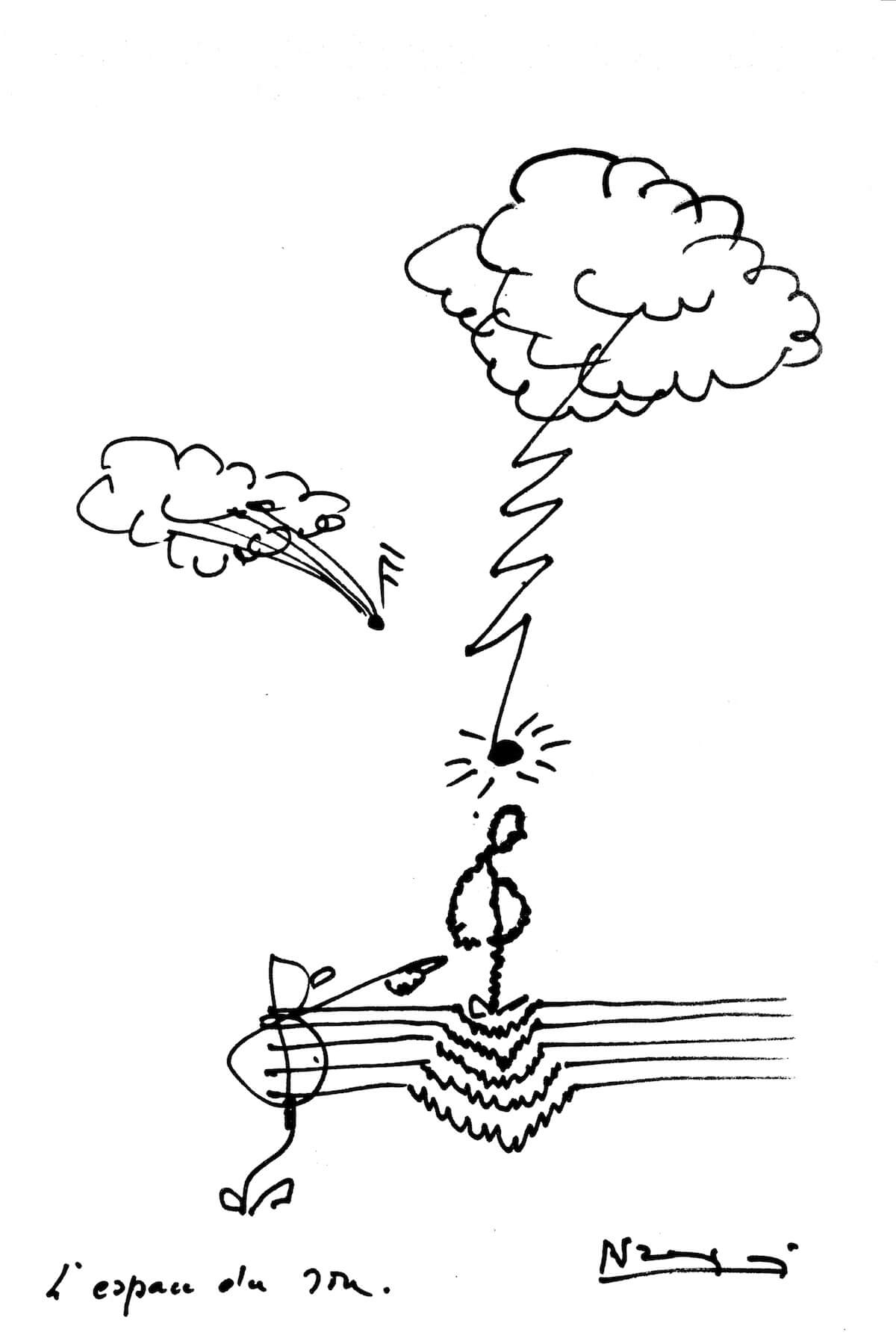

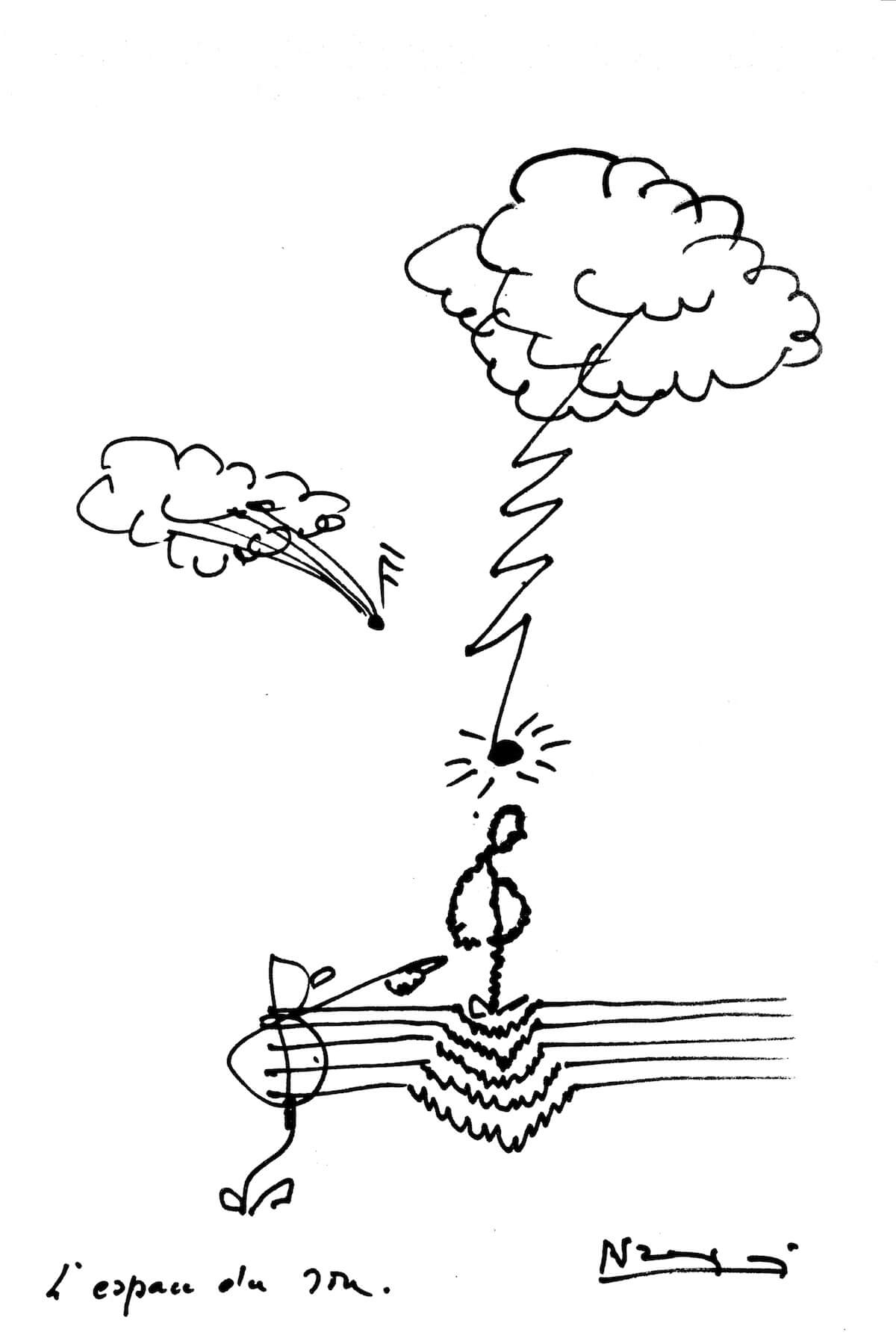

The Space of Sound

I also practiced mime from 1955 to 1959 with the late Jacques Lecoq and with Maximilien Decroux, son of the famous Etienne Decroux who'd taught amongst others Jean-Louis Barrault and all the great actors of the time. This discipline helped me a lot in my music. Marcel Marceau, who I'd met several times, explained to me that “miming is the act of cutting up space with the body”, with the hands. I particularly liked inventing exercises for transforming gestures with mime. I talk about this sometimes with regard to some of my pieces. In fact I'd always wanted to create a piece for mime where the sounds and the phyiscal gestures would be based on transformation, whether they be contrary to or compatible with one another, or that the types of transformation differ slightly from one another.

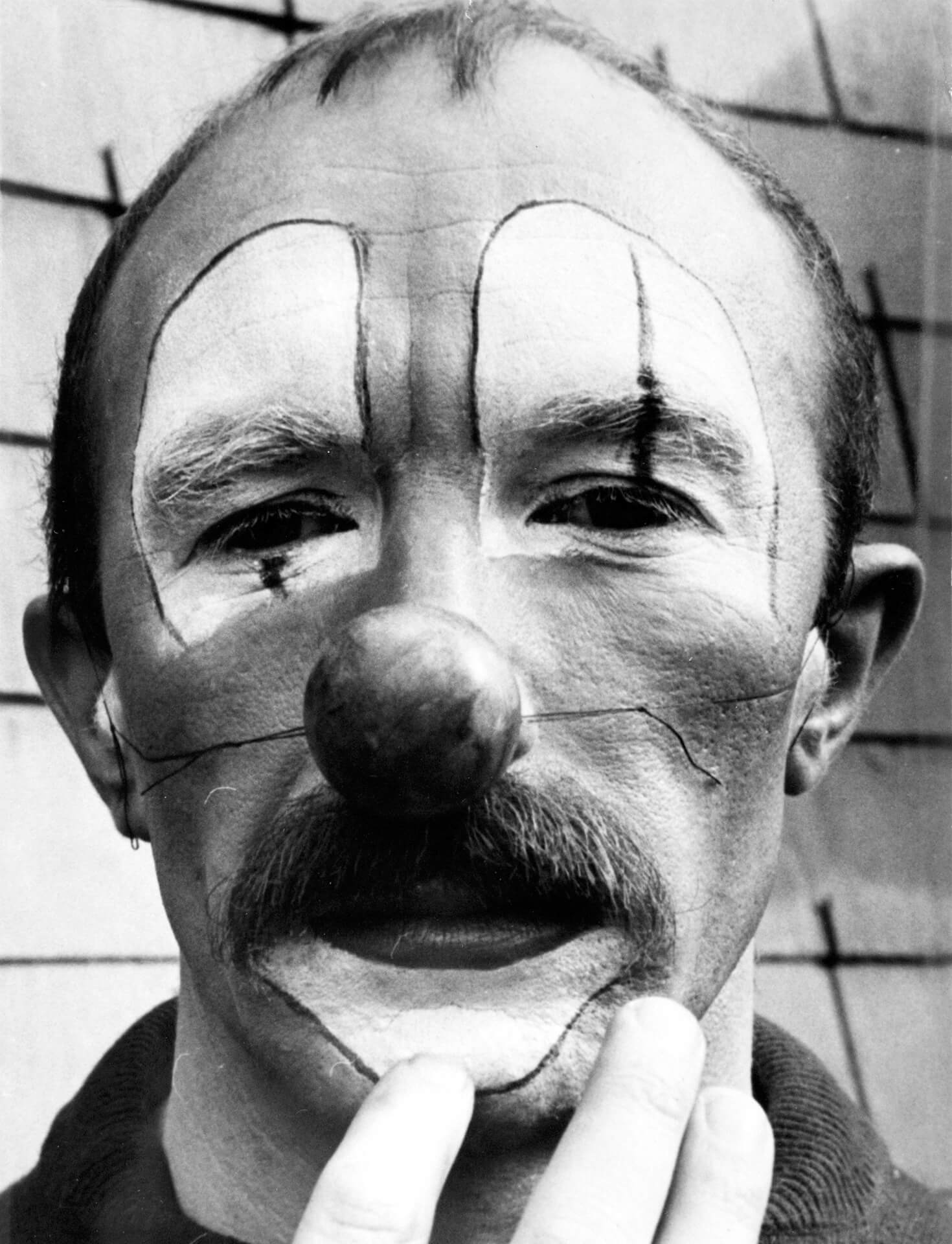

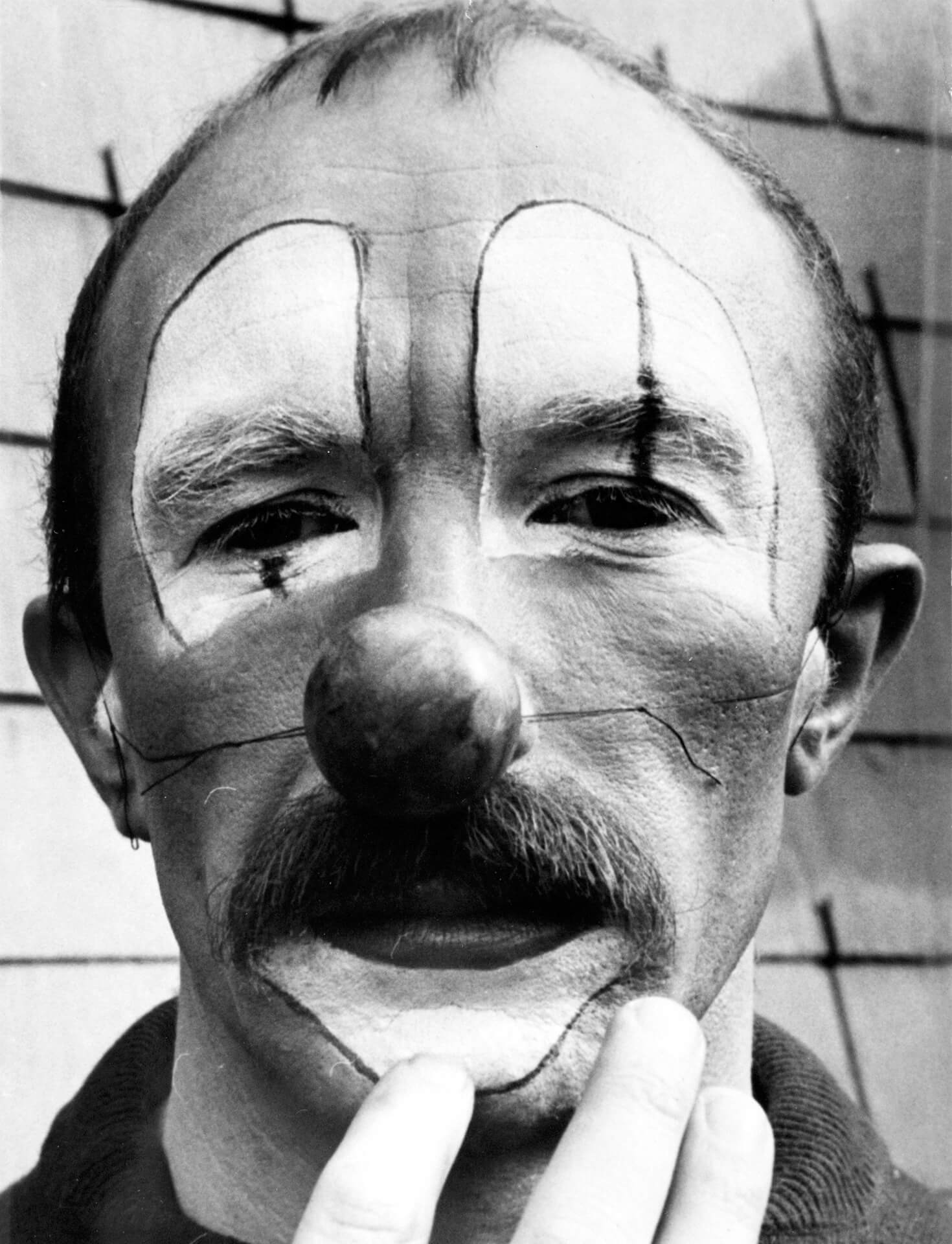

Wasn't it the Phonosophobe project in 1962 where you had wanted to make music and mime at the same time?

Yes, it's the first piece that I'd written. It was a sort of a first attempt. But the idea was already there and I would've liked to take it further with another mime. It was at this time Schaeffer intervened, saying, “Parme, you have to choose between music and mime”. And he was right, because miming took up a lot of time; it's a demanding exercise, after all – the body has to be trained daily, often in positions for improving balance. Moreover, I was involved in a children's TV show called “Le jeu des métiers” [The Profession Game] in which I mimed different professions. It was par for the course that one day I'd have to make a choice. Later on, Schaeffer hadn't forgotten my mime training when he presented l'Operabus in Zagreb in 1965 and asked me to play the role of the white clown...

The Collective Concert

When the GRM became part of the Research Service in 1960, you were there already since October 1959 and yet you still had to complete the GRM's “training course”. Why did you have to go through this initiation, and what did you learn?

It was – I was about to say – destiny that if I wanted to get into composition I couldn't go any other way than by doing the training course in order to officially enter the GRM. I had the status of a sound engineer, but given my penchant for experimentation and invention of sounds, and above all my urge to become a composer, the only solution was to take the proper route. Also, when I was asked if I wanted to take part in the course, I said “yes” straight away, and out I came two years later, second in my class. There was also Ivo Malec, Philippe Carson, François Bayle, Romuald Vandelle, N’Guyen Van Tuong, and Philippe Betz. I don't think I've left anyone out.

Did the Collective Concert event happen after this course?

A little later. That had been a decisive moment because it was the first time that I'd taken part in a GRM event (1961-63). I felt like I was finally allowed to play with the big kids. The majority of the musical passages prepared by the various composers – namely, François Bayle, Ivo Malec, Luc Ferrari, Edgardo Canton, François-Bernard Mâche, Michel Philippot, Jean-Etienne Marie – were written for instruments or mixed media. So I pulled the music a little over towards my way of doing things. That is, since each of us had to take out and recompose extracts from the eight other composers' passages, I embraced an electroacoustic approach. I made my piece through montage, by mixing and juxtaposing the passages onto one another. I was one of the few, if not the only, to compose a passage of electroacoustic music played solely through speakers during the concert, while the others had been performed by instrument players in front of the audience. I called my piece Alternances.

In your opinion, your first work is Violostries. You'd started off with nine sounds taken from Devy Erlih's violin.

After listening to Alternances, Devy Erlih asked me if I'd be interested in composing a piece for tape and violin. It was naturally understood that I'd write the tape part and he the violin part. As it happened, I made the tape part from nine recorded violin sounds first, and once it had been finished Devy wrote the violin part which in fact took the role of an additional voice within the mix. To come back to the figure of 9, it was Devy Erlih who wanted to put in place a system with nine elementary sounds. Certain notes were placed a fifth or a third apart, in ascending/descending order. I don't remember exactly what his system was because I hadn't used it for the tape. I never used a compositional system for that matter, no more in Violostries, which was still my first piece, than in my later work...

Violostries was back in 1965. You were already at the brink of maturity. What were your inspirations? Your influences?

To be completely honest, I don't think I had any real musical influences since I've always been forging my own path alone. I did however really like music of Ferrari's that I listened to over and over on rare vinyls because they piqued my interest. I enjoyed his character too, with his taste for the quaint and the absurd. I shared his insolent sense of humour, sometimes pushed to derision. Of course, I also had favorites from more classic repertory like Debussy, Ravel, Stravinsky, Bartok, etc.

My question about your influences could go further. You talked before about how your miming experience marked you, and just now you mentioned your interest in Luc Ferrari's music. What about literature – Bachelard, for example?

That came later. After reading Gaston Bachelard's essays on the poetic imagination of the four elements around 1965, I discovered his works about time. L’Intuition de l’instant and La Dialectique de la durée were the starting points for two works composed after Violostries:- L’Instant mobile (1966) and Capture éphémère (1967), which go together. Bachelard's thoughts about time were above all concerned with what he called “lived time”, with the sequence of moments.

Did you get anything from reading the Surrealists?

I didn't really learn anything by reading the Surrealists but by their attitude towards the world which, for me, unveiled (in every sense of the word) a surprising and bizarre vision that I felt close to. I had of course read André Breton, especially Nadia, Les Vases communicants, le Dictionnaire de l’humour noir, and Desnos, and Soupault.

But even more than literature, it was Bunuel's and Cocteau's images, and their cinema, that interested me the most.

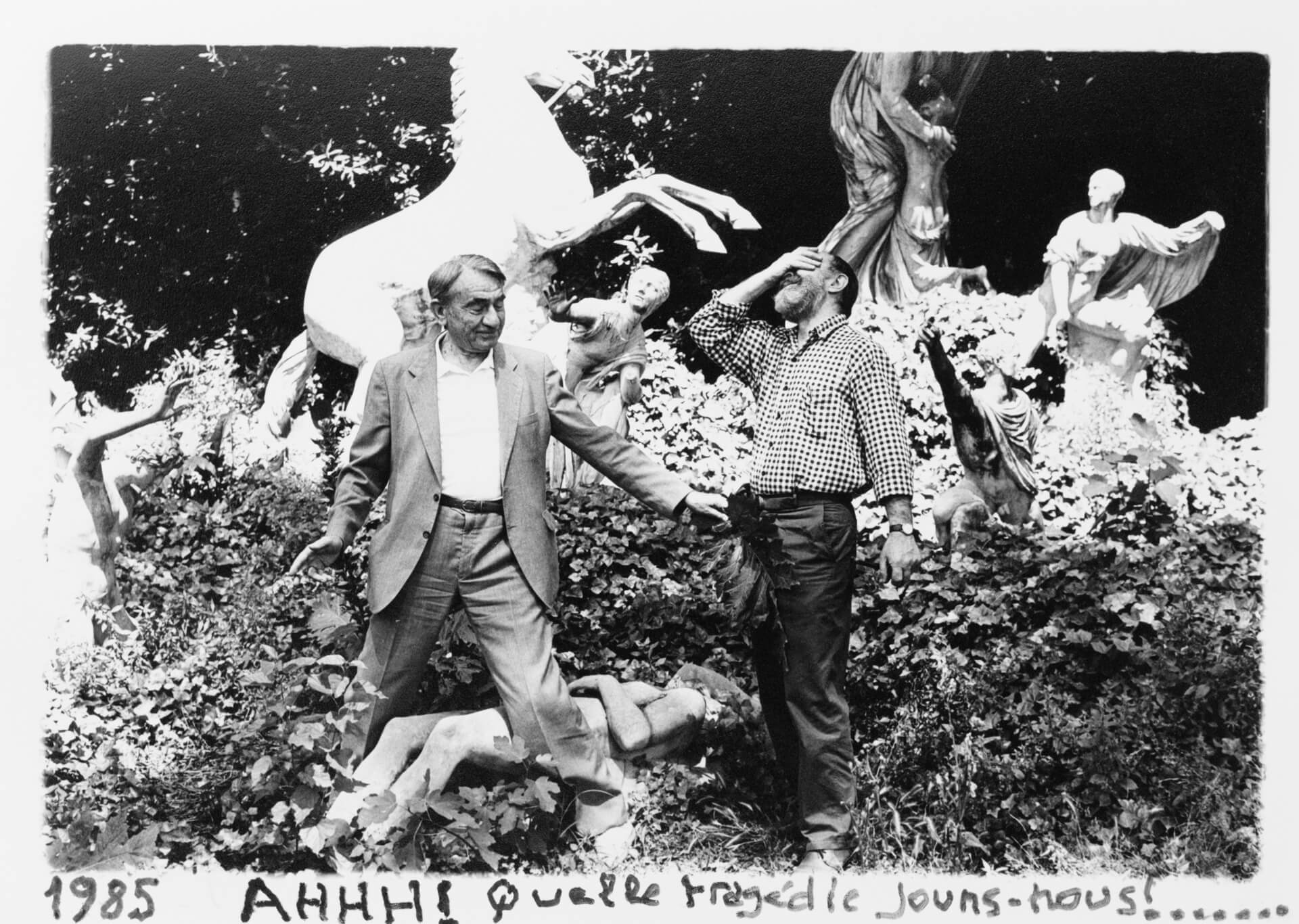

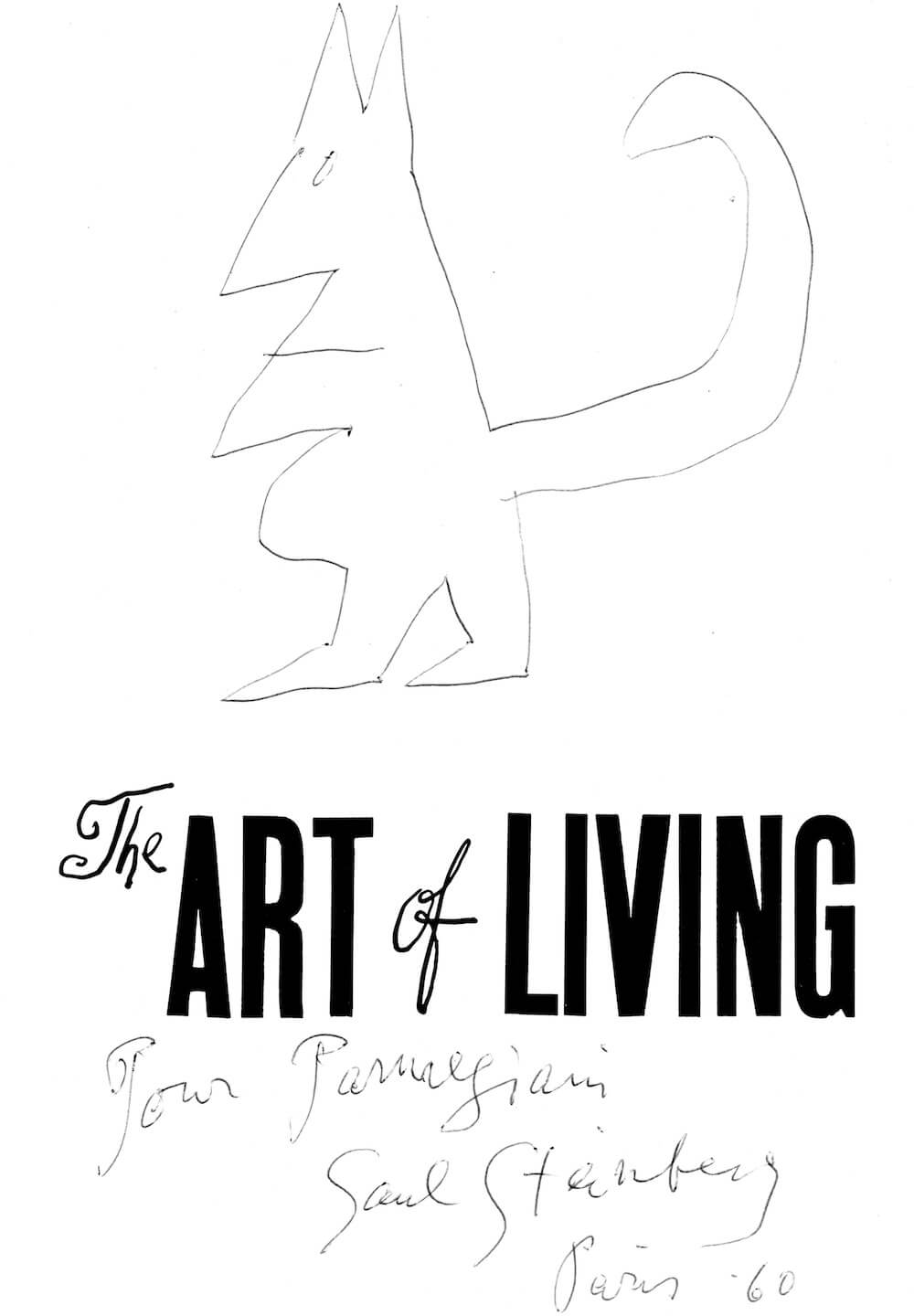

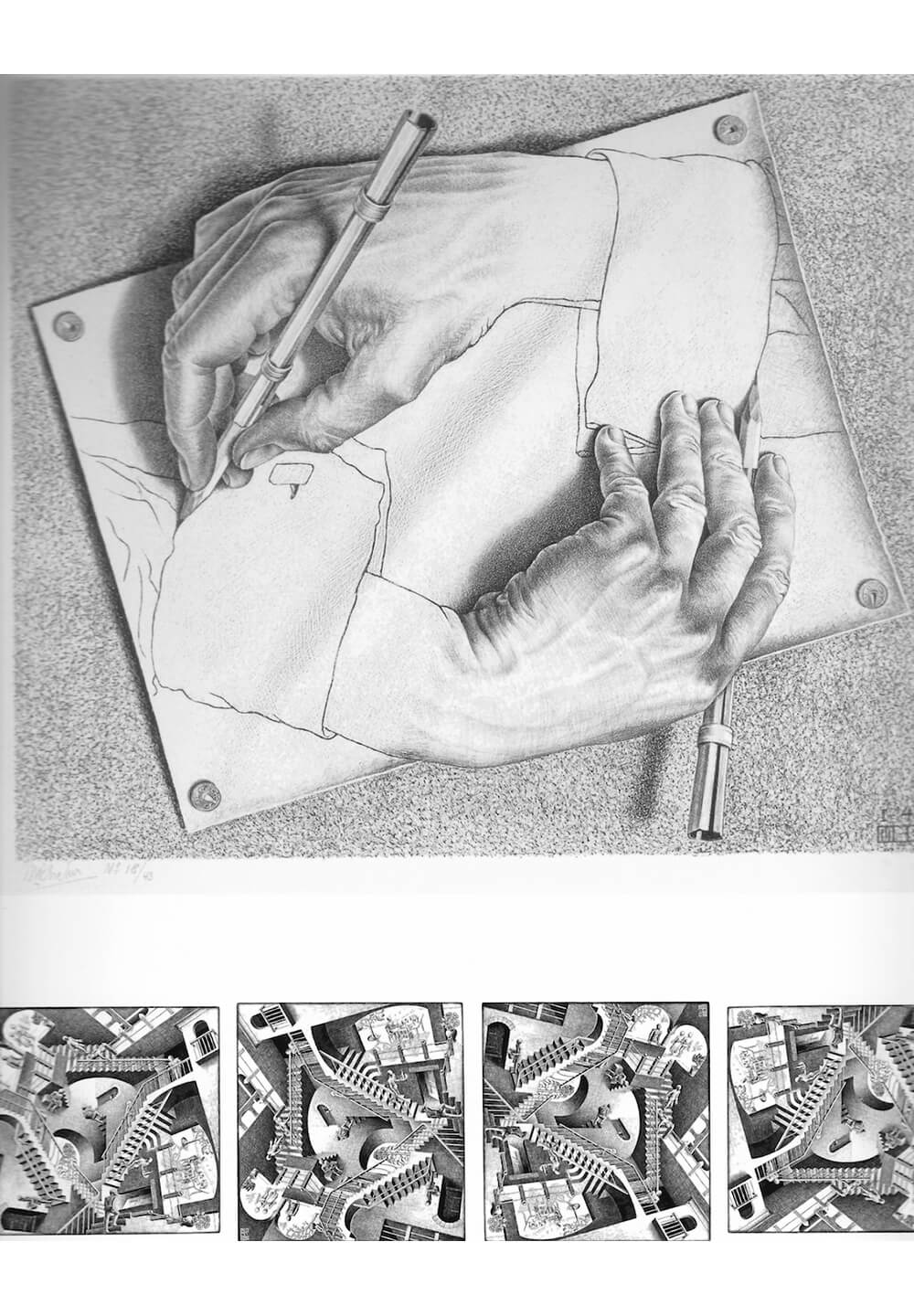

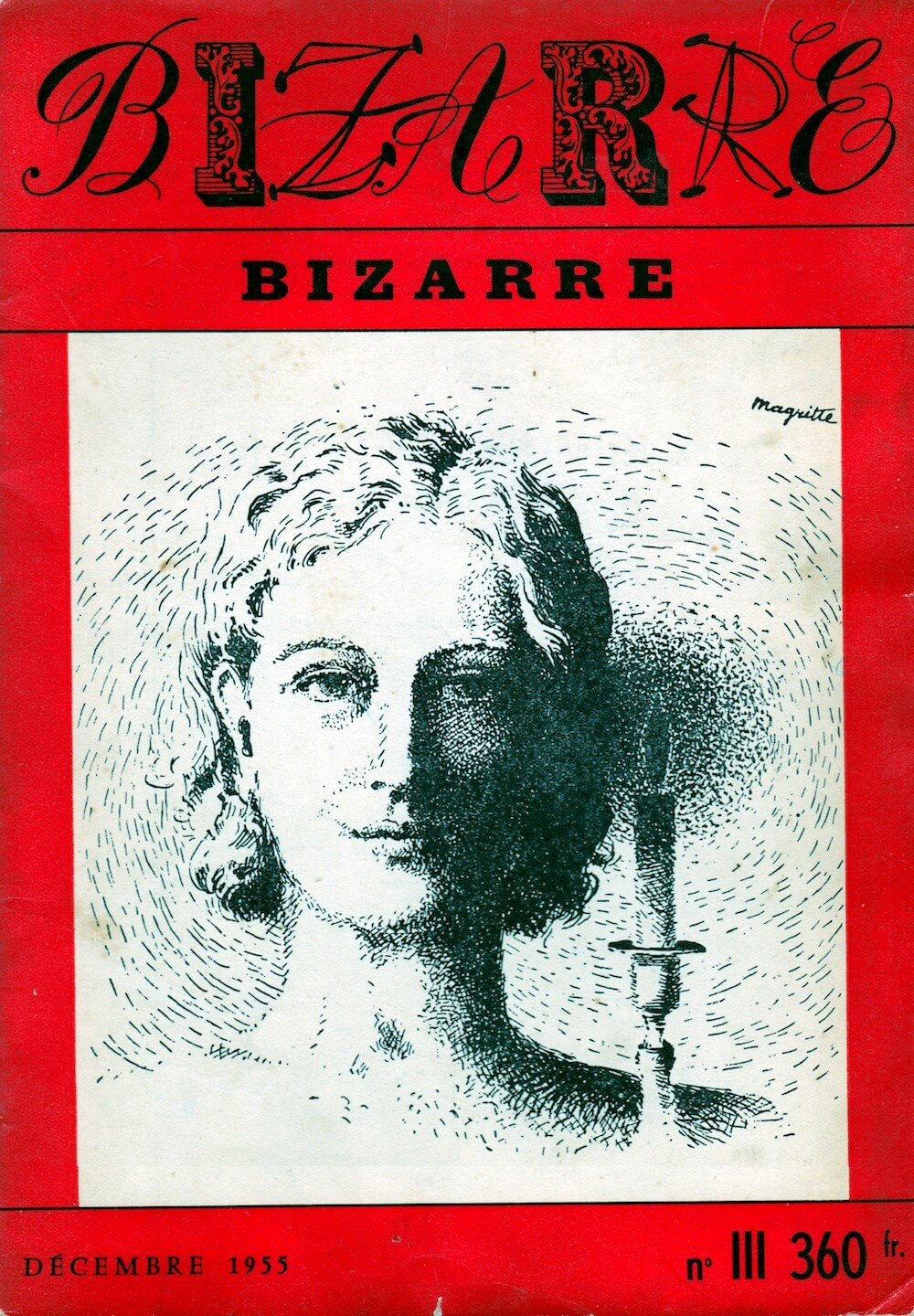

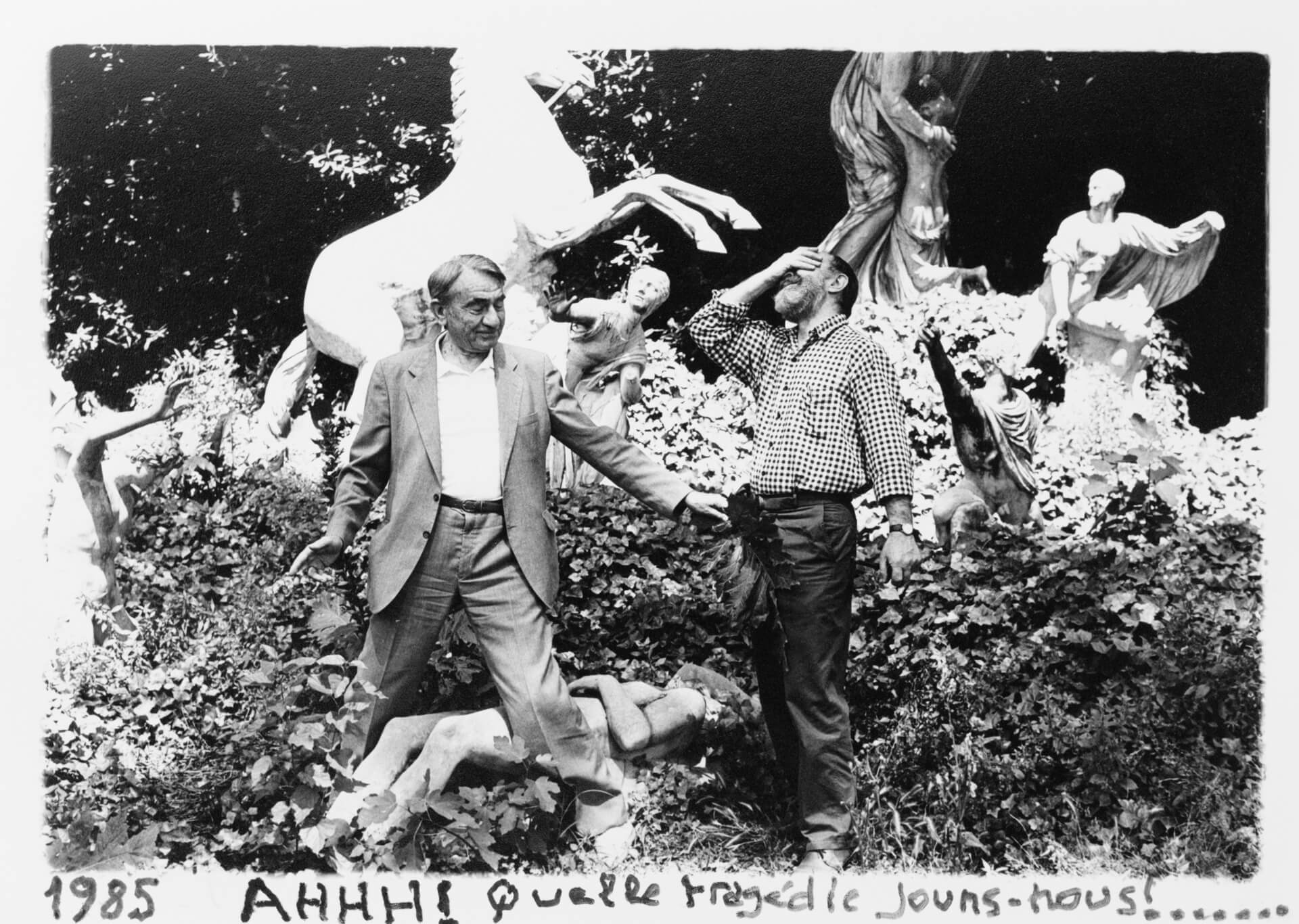

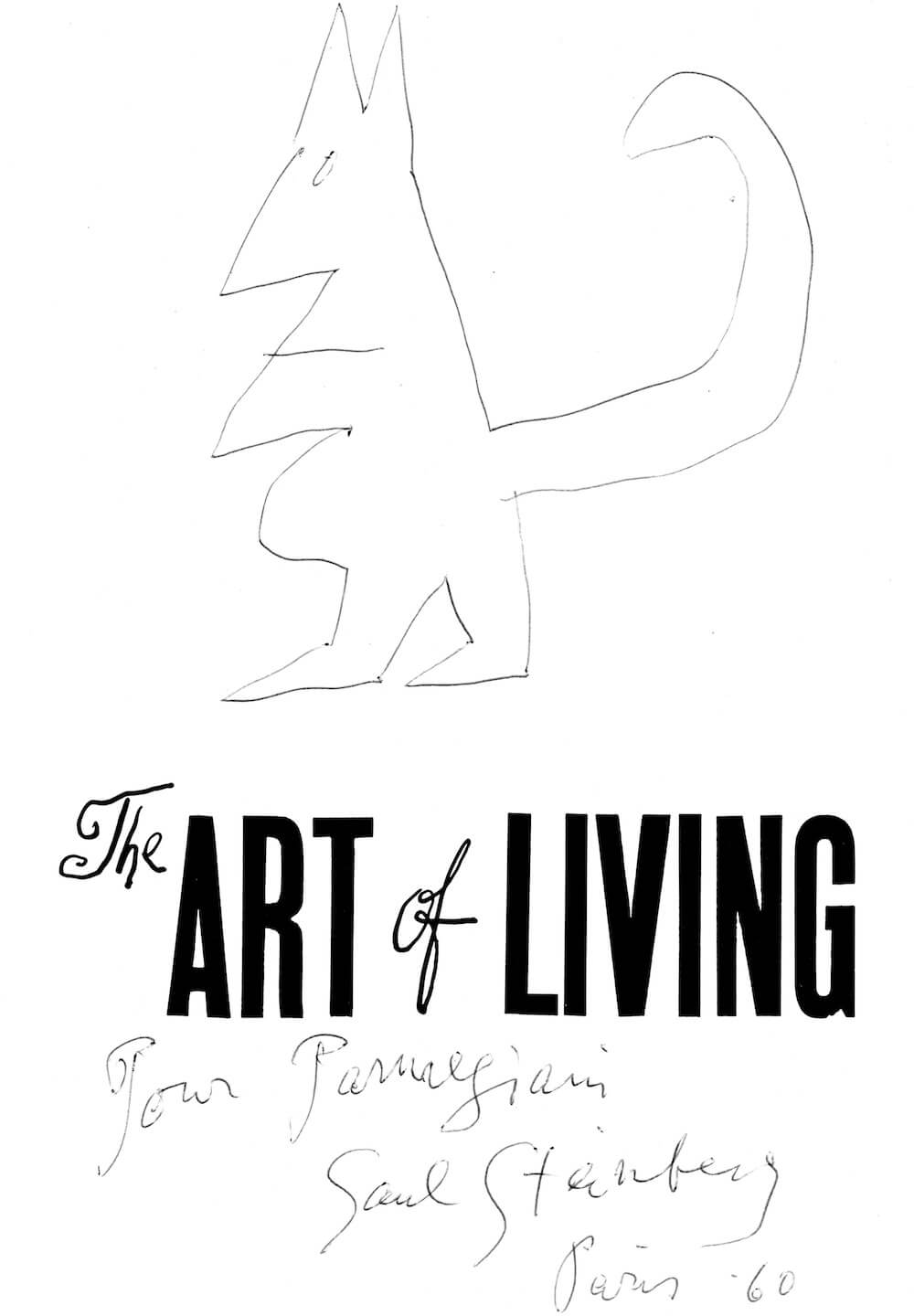

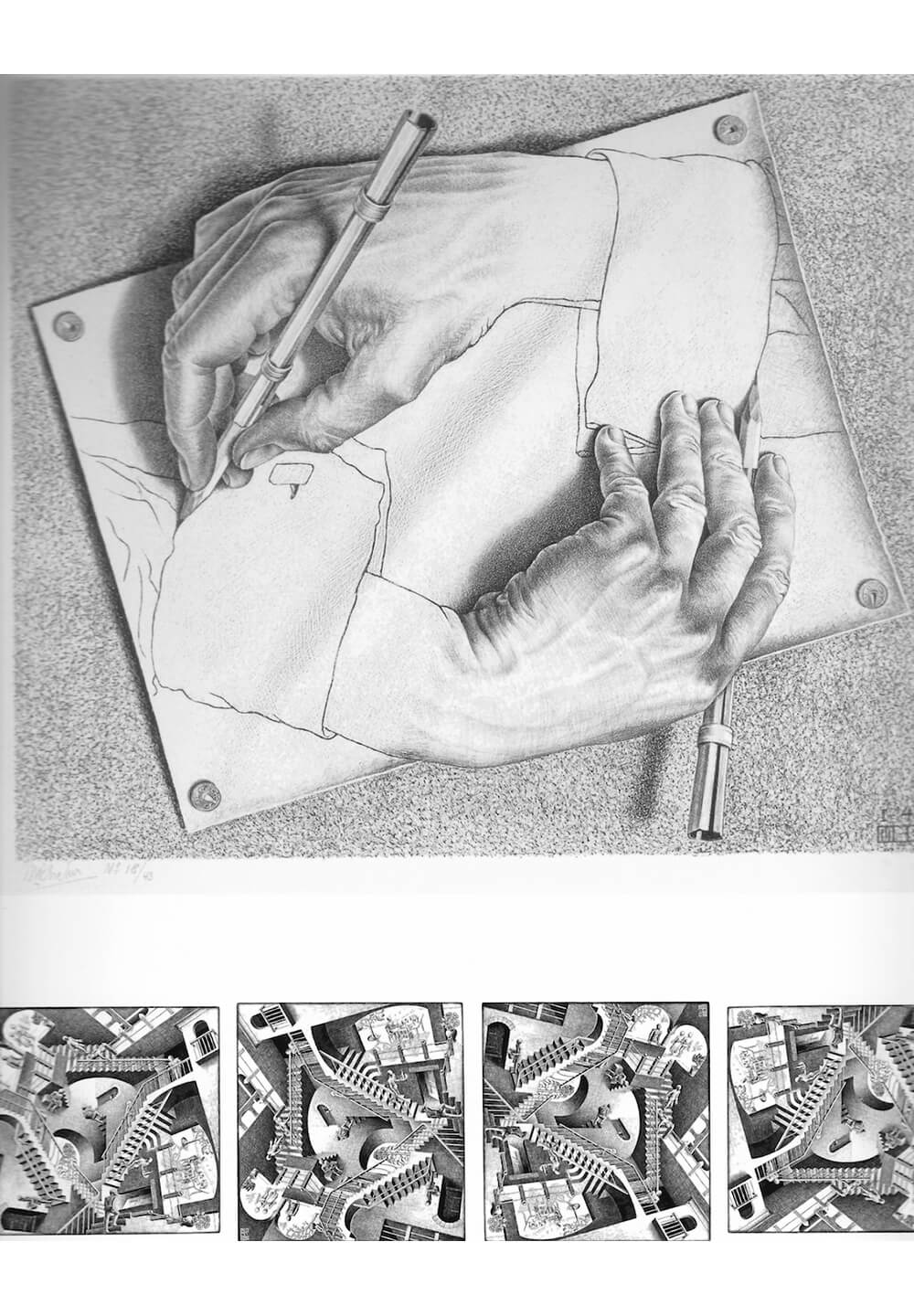

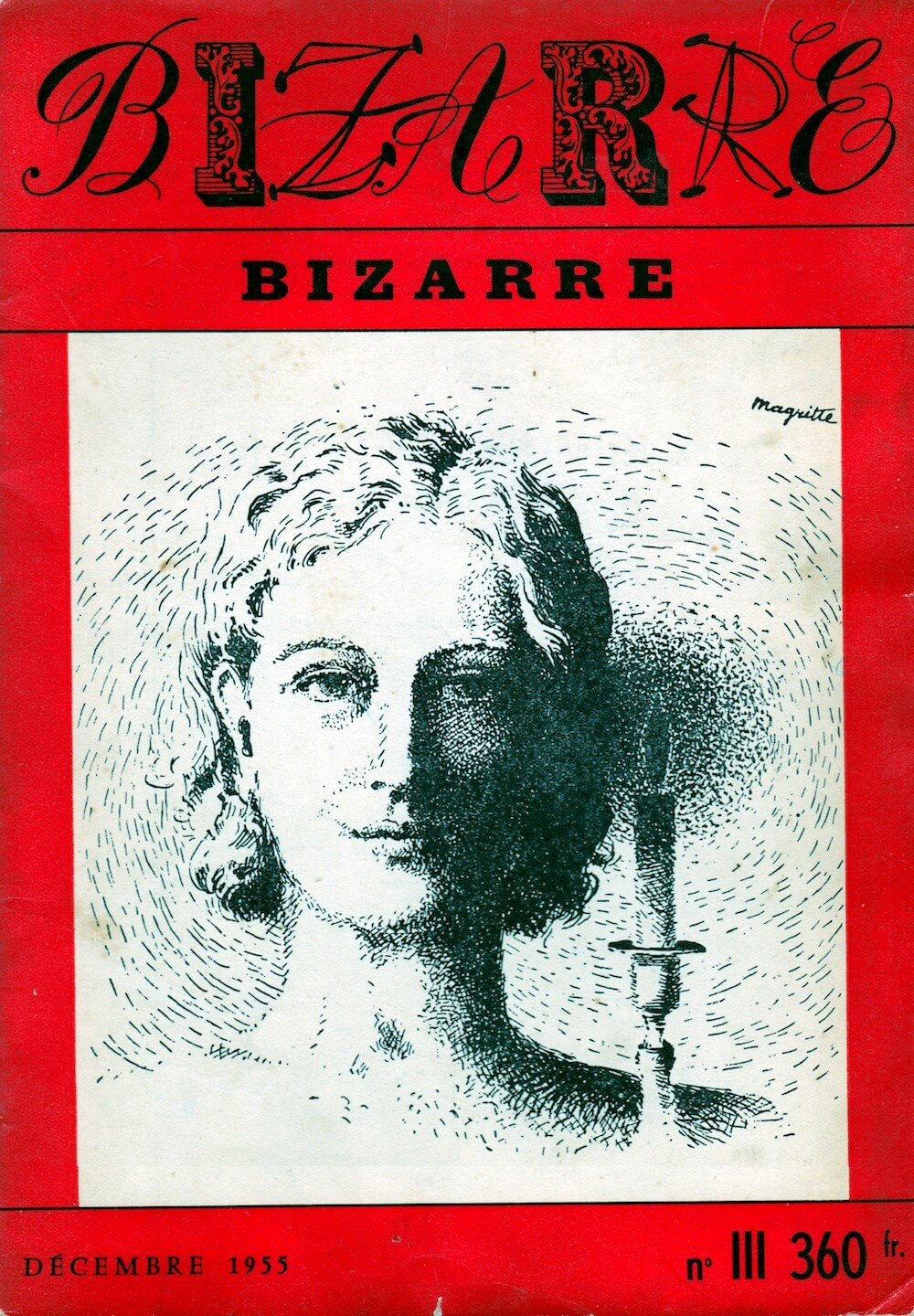

I was also intrigued by their use of the dream-world, their game-like practices such as the “cadavre exquis” which ended up as unexpected texts, sometimes absurd, sometimes funny, occasionally poetic. And then, I found editions of the journal Bizarre at the Librairie du Minotaure, where I discovered the stories and images of André François, Ronald Searle, Chaval, etc. I was fascinated by the drawings of Escher and Steinberg, who I met later on at the screening of one of Peter Kassovitz's short films that I'd written the music for. Every kind of representation is valid for Steinberg. In his representation of the every-day, the abstract can interfere with the concrete, it can introduce ambiguity which takes on a nonsensical character by playing with logic.

I feel the need to be disconcerted by what I see and what I hear. I enjoy the unexpected because we laugh when we're surprised and laughing is a characteristic of mankind; well, I am a man, so laughing is characteristic of me! This is why Lewis Carroll's texts have been part of my bedside reading for so many years, especially Syllogisms and Alice In Wonderland. Lots of nonsensical books have left their impression on me – on one hand because of their absurd nature and their playfulness with words which I also have, and on the other because of a sense of eccentricity which the Surrealists have, too. Saying “sense of eccentricity” makes me think of Clément Rosset, another philosopher who uses this term and who wrote some very wise things on electroacoustic music.

In fact, reading Clément Rosset's L'anti-nature helped me to define my musical intentions when was composing De Natura Sonorum. Later on, I discovered L'Objet Singulier in which he defines the problem of eccentricity or uniqueness, this thing which is self-referencing because lacking a copy. I almost borrowed a title from him, even.

Is it possible to define the Parmegiani sound? There are some that talk about organic sounds.

At one time, people alluded – a little too often, in my view – to the “Parmegiani sound”. That embarassed me enormously. They said to me, “Oh! Parme, what beautiful sounds you have!”. It's nice to make nice sounds, but really, you don't make music in order to make nice sounds, you create sounds to compose music with that comes from an idea. I'm not looking to charm people with my music, I'm looking to interest people, and this is why my overriding obsession is to constantly renew myself musically. Pursuing the discovery of new territories is one way to continue existing, otherwise you get bored with your own music. The risk is to do Parmegiani redoing Parmegiani, and so on. If I have to try to define what you call the “Parmegiani sound”, it's a particular mobility, a certain color, a way of beginning and bringing an end to a sound, and so giving it life. Because I consider sound a living being.

So there's truly something organic, skin-like, but it's always difficult to define your own music yourself. Whatever someone perceives from inside is not necessarily perceived from the outside in the same way. You recognize yourself more or less in the mirror someone hands to you – it's a game between “inside outside”.

The Anti-Method

We've talked about what you've read and you've described your way of working, with all those philosophical inspirations. First of all, you simply give yourself a title, a direction, and afterwards it's the sounds and the sonic material that take the helm in a very physical back-and-forth between your sensations and the sounds' transformations. But you can also sense a higher level to your work, a sort of yearning to be elevated.

This double dimension, if it's felt by some listeners, is not intentional since my working method is really very simple. The choice of the title makes the musical intent clear, and it gives me a general direction, but I mean really general. I therefore have to find a title which gives me some leeway for interpretation since I don't set out any strict plan before composing. Sometimes I even change the title if my intent has developed once the sounds have taken shape during composition. I never decide the number of movements nor their length beforehand.

When I begin a piece, I make up a repertory of sounds. Some are new sounds which I create, others are previously unused sounds which I think correspond to my intent, or old sounds which I transform. I listen to them and I make detailed inventories; it's a necessary part of my work method. For example, for De Natura Sonorum I drew up lists of sounds which I classified by shape, substance, color, etc. using all the typological terms featured in the TOM. I like to have the sonic matter I'm working with in my head, ready then to use in the way I intend. It's a process which takes me back to an activity I no longer do and which I haven't yet talked about.

Before making music, I made photomontages in the Surrealist assemblage vein. I cut out arms, heads, a hammer, a washing machine, a bowl with liquid pouring out of it, etc. from magazines and then I put them together to make an image with a new meaning from this unexpected juxtaposition... It's comparable to editing in electroacoustic music, where the choice of sounds gives a certain meaning to the juxtaposition of various forms.

A Moment of Time

Another theme which you're fond of is that of living in the present, searching how to place yourself in the moment and enacting philosophical concepts in real time.

There's nothing philosophical about this way of life. I'm naturally more inclined to live in the moment than live out a duration. Of course, I need reference points like anyone else, and I can do nothing other than take from my past experiences so that they contribute towards the present moment. Living completely in the present, I'm able to concentrate intensely on what I'm feeling and doing, as much in real life as in a creative period. Having an expeditious attitude enables me to accurately resolve problems which appear all of a sudden. My intellectual, even mental, energy is entirely dedicated to the present moment. I rarely think ahead to the future, which can occasionally get me into trouble because there are moments when you need to be able to take a step back to see the solution to a problem. I really use my past to back up the present, and it also helps me clear the path for the tunnel ahead that is the future.

The Five Senses

Skimming through the five senses, you could say that you mostly rely on your own personal, sensitive compass. At the heart of it, your music production reveals hearing itself. Beyond that, you've explored the visual through your work in image, TV, advertising, and video art. And within that there's also the physical, bodily side, working with space through miming.

I try to call on most of my senses as much in my day-to-day life as in my life as a composer.

Around the 1970's I was very concerned with the questions surrounding the relationship between sound and image so I went to the US to see what was happening with video art over there. The grandmaster at the time was a Japanese by the name of Nam June Paik. I also met Ed Ernswhiller, who had done productions where the choreography was processed through an image synthesizer and which produced very unexpected results. Pretty much at the same time Ron Hays had made a video inspired by Wagner's Prelude to Tristan and Isolde where the image's development brings about a continual feeling of the infinite. For me, this output is very influential to the work in the music-and-image connection.

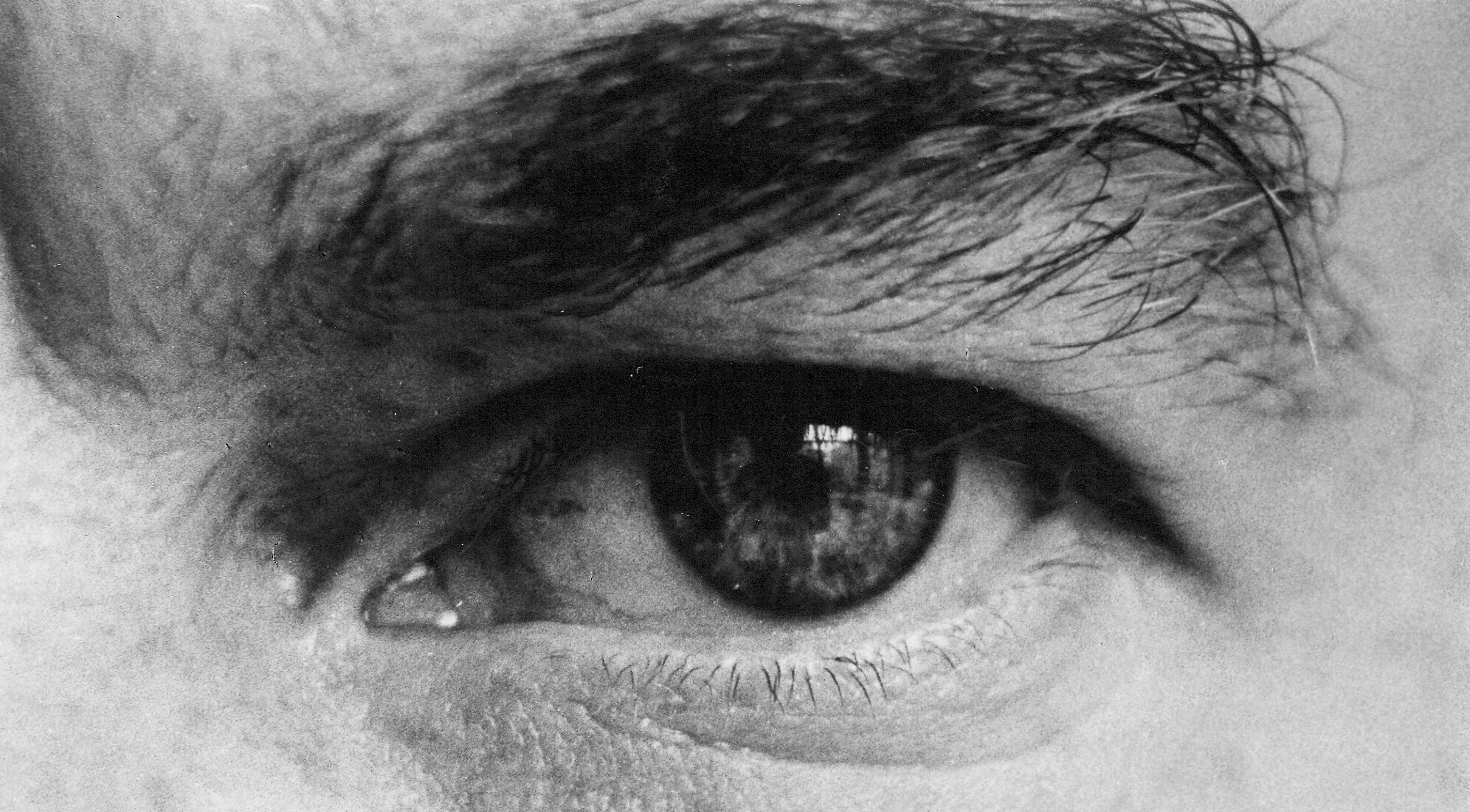

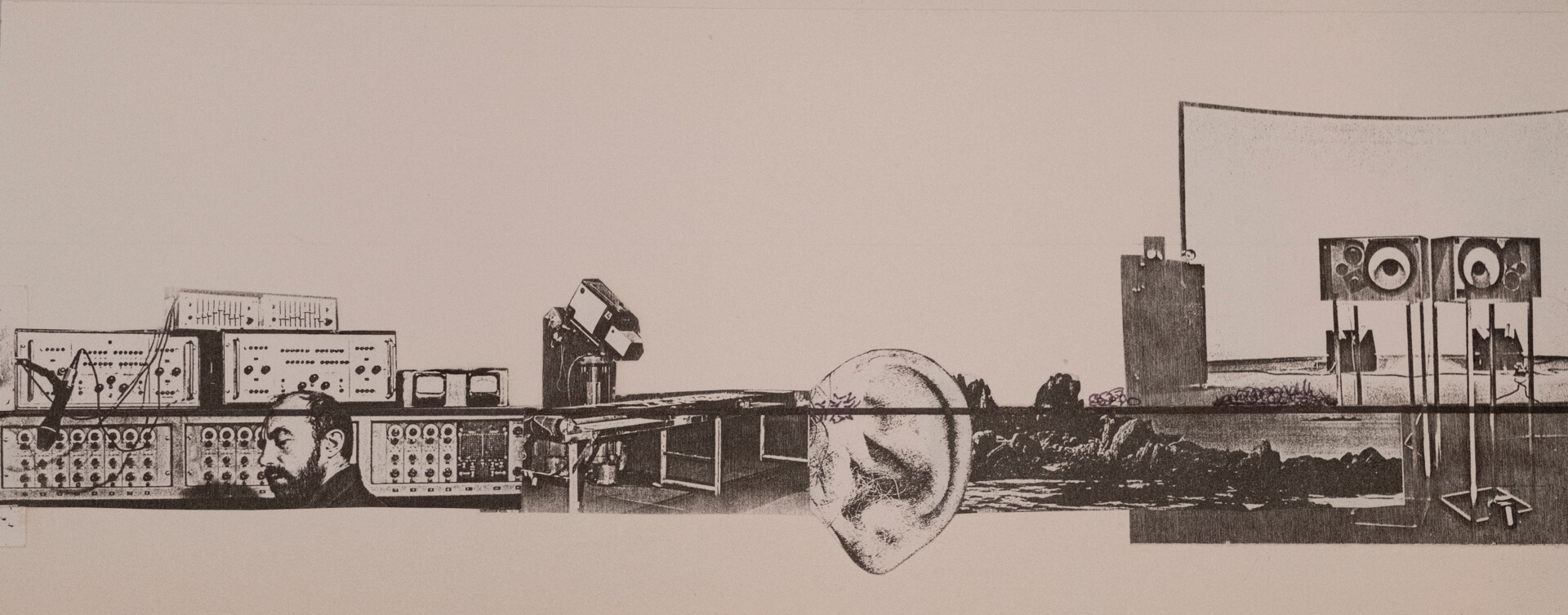

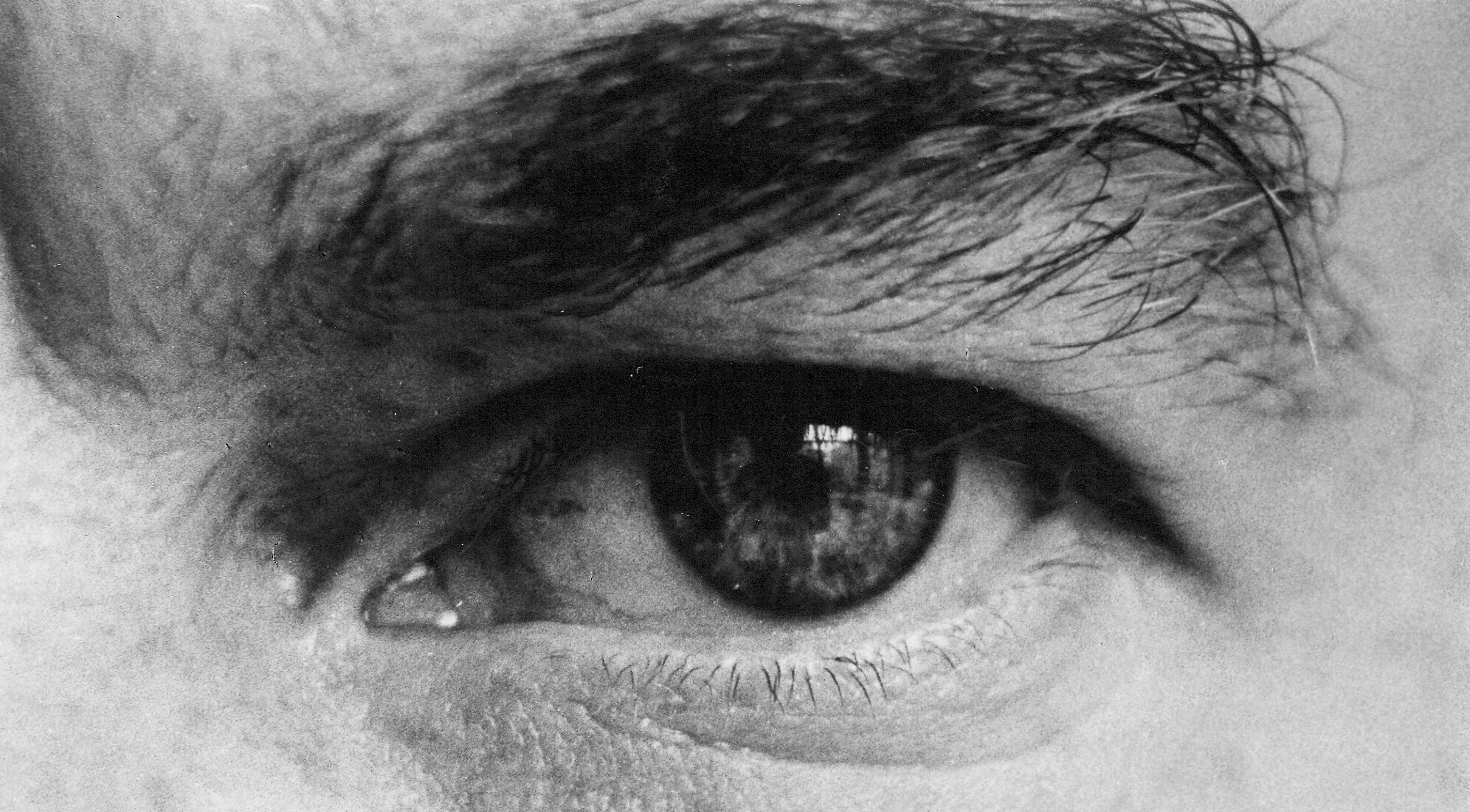

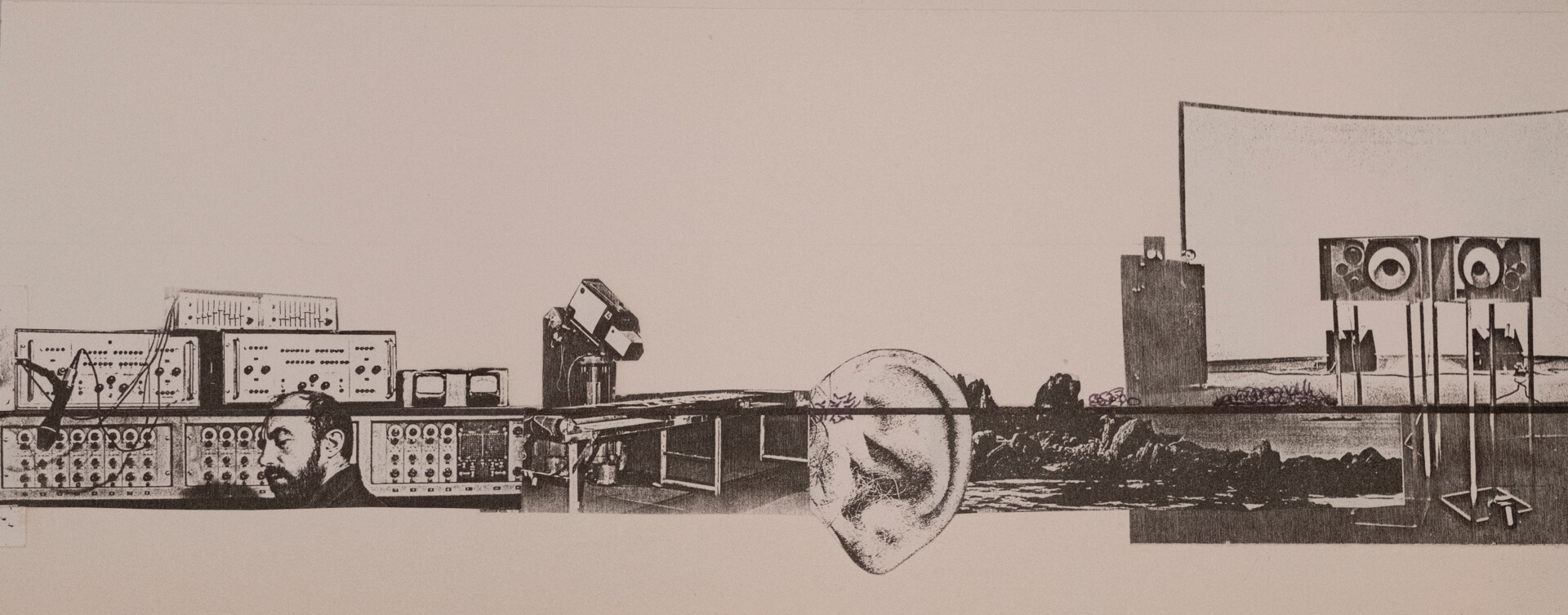

When I got back, I wanted to make some audiovisual experiments using pre-existing music. So, using images of my eye, or rather my eyes, I made L’Œil Ecoute with the Research Service's image synthesizer at the ORTF. The photos were taken by Valerian Borowczyck, a Polish filmmaker I was working with at the time. It was an investigation into the relationship between shape and substance. Using the image synthesizer, I processed the images from the eye photos together with the sounds. Later on, I wrote and co-produced L'Ecran Transparent wth José Montés-Baquer of the WDR (Westdeutscher Rundfunk) in Cologne.

I then tried one final experiment at the Research Service called Jeux d'Artifices. As its name implies, it's an illusory sound display which goes together with an illusory visual display to make a video about 12 minutes long. It was a very interesting experiment that I would've liked to take further, but I just didn't have the technical means.

The Matter of Space

How do you envision a piece's spatialisation when you perform it? Is it in view of making a show out of it or simply a moment to be lived through?

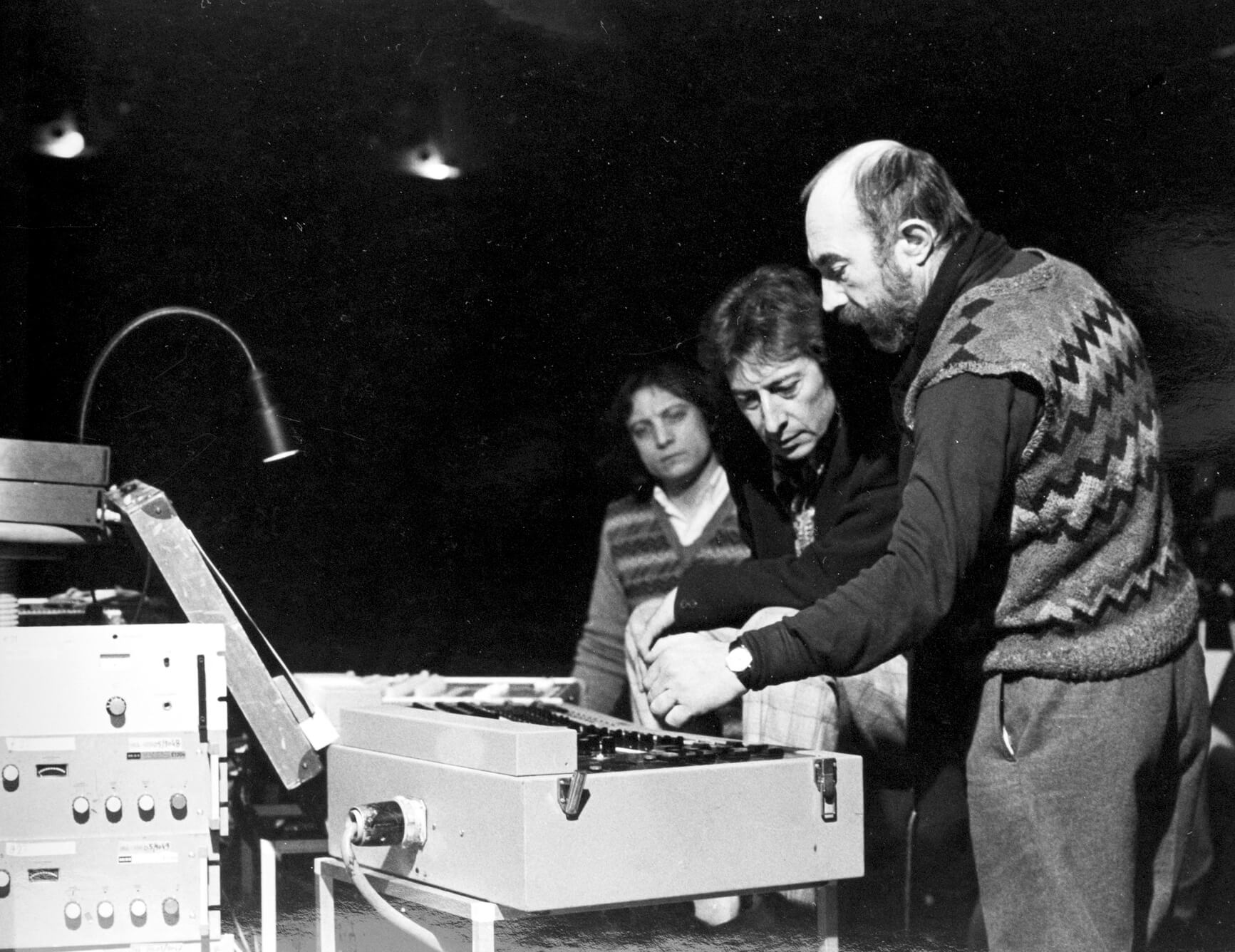

The word “show” makes me uncomfortable because there's a demonstrative side to it. I prefer the term “lived-through moment” because I never project the sounds the same way twice. When I'm in front of the mixing table during a concert, I evidently channel the sounds through specific speakers, going to the left, the right, on the sides, behind, etc., and I pair them. The sound could follow a trajectory, remain motionless within a speaker zone or even one pair of speakers. It's mediocre when certain composers, especially when they're first starting, open up all the faders and make very few alterations in overall volume. Worse still, the sound coming constantly from all sides is swamped. Then depending on the acoustics of the room you can even have cases where the reverberation or interference is so great that the listener can no longer distinguish any nuance.

Your Relationship with Technology

You lived through the great revolution from analogue to digital. Do you think these new tools have brought a new dimension to your music?

I believe I was the first at the GRM to buy my own equipment and have my own personal studio. I had to then teach myself how to work with digital devices. We all progressed on certain fronts and lost out on others, going from the scissors to the mouse. Analogue formats let you do things which became difficult and even impossible with digital. There are even sounds which you could create through analogue which you can't even get through digital, because of whichever program's design. Work habits being essentially different meant changes in technique for writing acoustically. Nonetheless you have to admit that the artisinal technique with scissors was quite tedious, whereas writing with the mouse is in some way quicker. The time between having an idea and realizing it is cut down, and so we're getting nearer to a real compositional act. But I can't use a new program without totally mastering all its functions. I like to go beyond the limits of ordinary instruments, diverting them from their recommended functions, which requires lots of time and effort to dominate. I don't actually use the machines for the effects they're capable of making but as tools for processing my sounds.

One Last Question

Given your age and experience, we might expect to see you looking to pass something on to others. You've passed on the passion for composing to some, of course. But you've never done any teaching, why?

First of all I'd say that I just don't have the educational touch. I'm not essentially a talkative person, nor very communicative. Whatever it is I have to say, I say doubtless more through my music than through any rhetoric. I feel forever unsatisfied, I feel like I'll have left something important out. I have a slow pace.

In Canada recently I gave a three-hour lecture at the Université de Montréal, after which I had to speak for another hour on the radio. I realized that I was wrong a lot of the time. Education works both ways – you learn a lot through the questions people pose you. Despite everything, I'm afraid of speaking and so I prefer to leave it to the music.

Mots de l’immédiat

Extract from a 2002 interview between Bernard Parmegiani and Évelyne Gayou, published in extenso in Portraits Polychromes Bernard Parmegiani (Ina, 2002-2007).

Évelyne Gayou :

This is what I know about you so far: you were born in 1927 and you spent your childhood between two pianos – your mother's and your father-in-law's, both piano teachers. So being young and without much choice given the circumstances, you studied this instrument.

Bernard Parmegiani :

I was in some sense “stuck between two pianos”, and this is actually true since there was on one side of my bedroom my father-in-law's room, the virtuoso pianist who taught the best and most advanced students from the Conservatoire, and on the other side was my mother who went through “do-ré-mi-fa-sol-la-si-do” with the little children to whom she taught Scarlatti. She's the one who made me work for many years. I would occasionally have lessons with my father-in-law but it was rare because he was very busy or on tour. But when I worked on the piano I spent a lot of time improvising based on what I'd been hearing. I tried to do Ravel, Debussy, Beethoven, or Mozart and sometimes even some Parmegiani […]. I wouldn't have hated becoming a pianist, but it didn't take off.

Afterwards, you went off to do your military service at the Army Cinema Service for three years, and then you went into radio.

Before going into radio I'd prepared for a competition for radio producers. Unfortunately I came 7 out of 100... And there were only 5 places at Paris while the others were sent outside of the capital. Since I didn't want to leave Paris I had to abandon producing and I got into radio […] as an assistant operator for a year and a half. There, I was taught techniques for recording at the radio which rounded off the Army Service Cinema training in recording sound for film. After that I went into television where I would stay for three years. At the beginning I was a sound engineer, that is, boom operator, for TV dramas – holding the boom up, underneath the projectors. It was quite gruelling work. Then, eventually, I got to the console. And when you become team leader, you get to fiddle with the knobs.

During this time I would also visit the Research Centre for Radio and Television at the Club d'Essai. I went to conferences on broadcasting, sound recording, radio esthetics, etc. and there I met André Almuro. Since I had begun to make sound montages on tape for animations and radio adverts, he invited me to come work at the Maison des Lettres to make what they were calling “experimental” music. I did that on the sly when the studios were empty.

André Almuro was writing a piece which was called, would you believe it, De Natura Rerum, after Lucretius. So it wasn't far to go from De Natura Rerum to De Natura Sonorum, even if there are sixteen years between them and they share neither the same aims nor musical forms.

Anyway, one day, Schaeffer came to see us in our little studio to listen to our work which he glowingly praised. After that, we analyzed La Symphonie pour un homme seul together. Following this brief encounter, Schaeffer invited Almuro to join the Research Service in the capacity of a composer, and Almuro asked that I be able to come with him as a sound engineer. But in order for that to happen, I had to leave television. Schaeffer himself, a few months later, literally tore me away from my post as sound engineer for TV, and at the Groupe de Recherches Musicales I simultaneously became a fully-fledged sound engineer and assistant editor. I started out helping Xenakis, Ferrari, and then others. I knew these people by name before joining the GRM because since 1951 I'd been listening a lot to the Club d'Essai (at the Univeristy of Paris) which was directed by the poet Jean Tardieu and which housed the GRM studios. I listened to the musique concrète concerts every sunday and of course I'd heard pieces by Luc Ferrari, Pierre Schaeffer, Pierre Henry – those were the three main ones – and François-Bernard Mâche came along a little later.

The Space of Sound

I also practiced mime from 1955 to 1959 with the late Jacques Lecoq and with Maximilien Decroux, son of the famous Etienne Decroux who'd taught amongst others Jean-Louis Barrault and all the great actors of the time. This discipline helped me a lot in my music. Marcel Marceau, who I'd met several times, explained to me that “miming is the act of cutting up space with the body”, with the hands. I particularly liked inventing exercises for transforming gestures with mime. I talk about this sometimes with regard to some of my pieces. In fact I'd always wanted to create a piece for mime where the sounds and the phyiscal gestures would be based on transformation, whether they be contrary to or compatible with one another, or that the types of transformation differ slightly from one another.

Wasn't it the Phonosophobe project in 1962 where you had wanted to make music and mime at the same time?

Yes, it's the first piece that I'd written. It was a sort of a first attempt. But the idea was already there and I would've liked to take it further with another mime. It was at this time Schaeffer intervened, saying, “Parme, you have to choose between music and mime”. And he was right, because miming took up a lot of time; it's a demanding exercise, after all – the body has to be trained daily, often in positions for improving balance. Moreover, I was involved in a children's TV show called “Le jeu des métiers” [The Profession Game] in which I mimed different professions. It was par for the course that one day I'd have to make a choice. Later on, Schaeffer hadn't forgotten my mime training when he presented l'Operabus in Zagreb in 1965 and asked me to play the role of the white clown...

The Collective Concert

When the GRM became part of the Research Service in 1960, you were there already since October 1959 and yet you still had to complete the GRM's “training course”. Why did you have to go through this initiation, and what did you learn?

It was – I was about to say – destiny that if I wanted to get into composition I couldn't go any other way than by doing the training course in order to officially enter the GRM. I had the status of a sound engineer, but given my penchant for experimentation and invention of sounds, and above all my urge to become a composer, the only solution was to take the proper route. Also, when I was asked if I wanted to take part in the course, I said “yes” straight away, and out I came two years later, second in my class. There was also Ivo Malec, Philippe Carson, François Bayle, Romuald Vandelle, N’Guyen Van Tuong, and Philippe Betz. I don't think I've left anyone out.

Did the Collective Concert event happen after this course?

A little later. That had been a decisive moment because it was the first time that I'd taken part in a GRM event (1961-63). I felt like I was finally allowed to play with the big kids. The majority of the musical passages prepared by the various composers – namely, François Bayle, Ivo Malec, Luc Ferrari, Edgardo Canton, François-Bernard Mâche, Michel Philippot, Jean-Etienne Marie – were written for instruments or mixed media. So I pulled the music a little over towards my way of doing things. That is, since each of us had to take out and recompose extracts from the eight other composers' passages, I embraced an electroacoustic approach. I made my piece through montage, by mixing and juxtaposing the passages onto one another. I was one of the few, if not the only, to compose a passage of electroacoustic music played solely through speakers during the concert, while the others had been performed by instrument players in front of the audience. I called my piece Alternances.

In your opinion, your first work is Violostries. You'd started off with nine sounds taken from Devy Erlih's violin.

After listening to Alternances, Devy Erlih asked me if I'd be interested in composing a piece for tape and violin. It was naturally understood that I'd write the tape part and he the violin part. As it happened, I made the tape part from nine recorded violin sounds first, and once it had been finished Devy wrote the violin part which in fact took the role of an additional voice within the mix. To come back to the figure of 9, it was Devy Erlih who wanted to put in place a system with nine elementary sounds. Certain notes were placed a fifth or a third apart, in ascending/descending order. I don't remember exactly what his system was because I hadn't used it for the tape. I never used a compositional system for that matter, no more in Violostries, which was still my first piece, than in my later work...

Violostries was back in 1965. You were already at the brink of maturity. What were your inspirations? Your influences?

To be completely honest, I don't think I had any real musical influences since I've always been forging my own path alone. I did however really like music of Ferrari's that I listened to over and over on rare vinyls because they piqued my interest. I enjoyed his character too, with his taste for the quaint and the absurd. I shared his insolent sense of humour, sometimes pushed to derision. Of course, I also had favorites from more classic repertory like Debussy, Ravel, Stravinsky, Bartok, etc.

My question about your influences could go further. You talked before about how your miming experience marked you, and just now you mentioned your interest in Luc Ferrari's music. What about literature – Bachelard, for example?

That came later. After reading Gaston Bachelard's essays on the poetic imagination of the four elements around 1965, I discovered his works about time. L’Intuition de l’instant and La Dialectique de la durée were the starting points for two works composed after Violostries:- L’Instant mobile (1966) and Capture éphémère (1967), which go together. Bachelard's thoughts about time were above all concerned with what he called “lived time”, with the sequence of moments.

Did you get anything from reading the Surrealists?

I didn't really learn anything by reading the Surrealists but by their attitude towards the world which, for me, unveiled (in every sense of the word) a surprising and bizarre vision that I felt close to. I had of course read André Breton, especially Nadia, Les Vases communicants, le Dictionnaire de l’humour noir, and Desnos, and Soupault.

But even more than literature, it was Bunuel's and Cocteau's images, and their cinema, that interested me the most.

I was also intrigued by their use of the dream-world, their game-like practices such as the “cadavre exquis” which ended up as unexpected texts, sometimes absurd, sometimes funny, occasionally poetic. And then, I found editions of the journal Bizarre at the Librairie du Minotaure, where I discovered the stories and images of André François, Ronald Searle, Chaval, etc. I was fascinated by the drawings of Escher and Steinberg, who I met later on at the screening of one of Peter Kassovitz's short films that I'd written the music for. Every kind of representation is valid for Steinberg. In his representation of the every-day, the abstract can interfere with the concrete, it can introduce ambiguity which takes on a nonsensical character by playing with logic.

I feel the need to be disconcerted by what I see and what I hear. I enjoy the unexpected because we laugh when we're surprised and laughing is a characteristic of mankind; well, I am a man, so laughing is characteristic of me! This is why Lewis Carroll's texts have been part of my bedside reading for so many years, especially Syllogisms and Alice In Wonderland. Lots of nonsensical books have left their impression on me – on one hand because of their absurd nature and their playfulness with words which I also have, and on the other because of a sense of eccentricity which the Surrealists have, too. Saying “sense of eccentricity” makes me think of Clément Rosset, another philosopher who uses this term and who wrote some very wise things on electroacoustic music.

In fact, reading Clément Rosset's L'anti-nature helped me to define my musical intentions when was composing De Natura Sonorum. Later on, I discovered L'Objet Singulier in which he defines the problem of eccentricity or uniqueness, this thing which is self-referencing because lacking a copy. I almost borrowed a title from him, even.

Is it possible to define the Parmegiani sound? There are some that talk about organic sounds.

At one time, people alluded – a little too often, in my view – to the “Parmegiani sound”. That embarassed me enormously. They said to me, “Oh! Parme, what beautiful sounds you have!”. It's nice to make nice sounds, but really, you don't make music in order to make nice sounds, you create sounds to compose music with that comes from an idea. I'm not looking to charm people with my music, I'm looking to interest people, and this is why my overriding obsession is to constantly renew myself musically. Pursuing the discovery of new territories is one way to continue existing, otherwise you get bored with your own music. The risk is to do Parmegiani redoing Parmegiani, and so on. If I have to try to define what you call the “Parmegiani sound”, it's a particular mobility, a certain color, a way of beginning and bringing an end to a sound, and so giving it life. Because I consider sound a living being.

So there's truly something organic, skin-like, but it's always difficult to define your own music yourself. Whatever someone perceives from inside is not necessarily perceived from the outside in the same way. You recognize yourself more or less in the mirror someone hands to you – it's a game between “inside outside”.

The Anti-Method

We've talked about what you've read and you've described your way of working, with all those philosophical inspirations. First of all, you simply give yourself a title, a direction, and afterwards it's the sounds and the sonic material that take the helm in a very physical back-and-forth between your sensations and the sounds' transformations. But you can also sense a higher level to your work, a sort of yearning to be elevated.

This double dimension, if it's felt by some listeners, is not intentional since my working method is really very simple. The choice of the title makes the musical intent clear, and it gives me a general direction, but I mean really general. I therefore have to find a title which gives me some leeway for interpretation since I don't set out any strict plan before composing. Sometimes I even change the title if my intent has developed once the sounds have taken shape during composition. I never decide the number of movements nor their length beforehand.

When I begin a piece, I make up a repertory of sounds. Some are new sounds which I create, others are previously unused sounds which I think correspond to my intent, or old sounds which I transform. I listen to them and I make detailed inventories; it's a necessary part of my work method. For example, for De Natura Sonorum I drew up lists of sounds which I classified by shape, substance, color, etc. using all the typological terms featured in the TOM. I like to have the sonic matter I'm working with in my head, ready then to use in the way I intend. It's a process which takes me back to an activity I no longer do and which I haven't yet talked about.

Before making music, I made photomontages in the Surrealist assemblage vein. I cut out arms, heads, a hammer, a washing machine, a bowl with liquid pouring out of it, etc. from magazines and then I put them together to make an image with a new meaning from this unexpected juxtaposition... It's comparable to editing in electroacoustic music, where the choice of sounds gives a certain meaning to the juxtaposition of various forms.

A Moment of Time

Another theme which you're fond of is that of living in the present, searching how to place yourself in the moment and enacting philosophical concepts in real time.

There's nothing philosophical about this way of life. I'm naturally more inclined to live in the moment than live out a duration. Of course, I need reference points like anyone else, and I can do nothing other than take from my past experiences so that they contribute towards the present moment. Living completely in the present, I'm able to concentrate intensely on what I'm feeling and doing, as much in real life as in a creative period. Having an expeditious attitude enables me to accurately resolve problems which appear all of a sudden. My intellectual, even mental, energy is entirely dedicated to the present moment. I rarely think ahead to the future, which can occasionally get me into trouble because there are moments when you need to be able to take a step back to see the solution to a problem. I really use my past to back up the present, and it also helps me clear the path for the tunnel ahead that is the future.

The Five Senses

Skimming through the five senses, you could say that you mostly rely on your own personal, sensitive compass. At the heart of it, your music production reveals hearing itself. Beyond that, you've explored the visual through your work in image, TV, advertising, and video art. And within that there's also the physical, bodily side, working with space through miming.

I try to call on most of my senses as much in my day-to-day life as in my life as a composer.

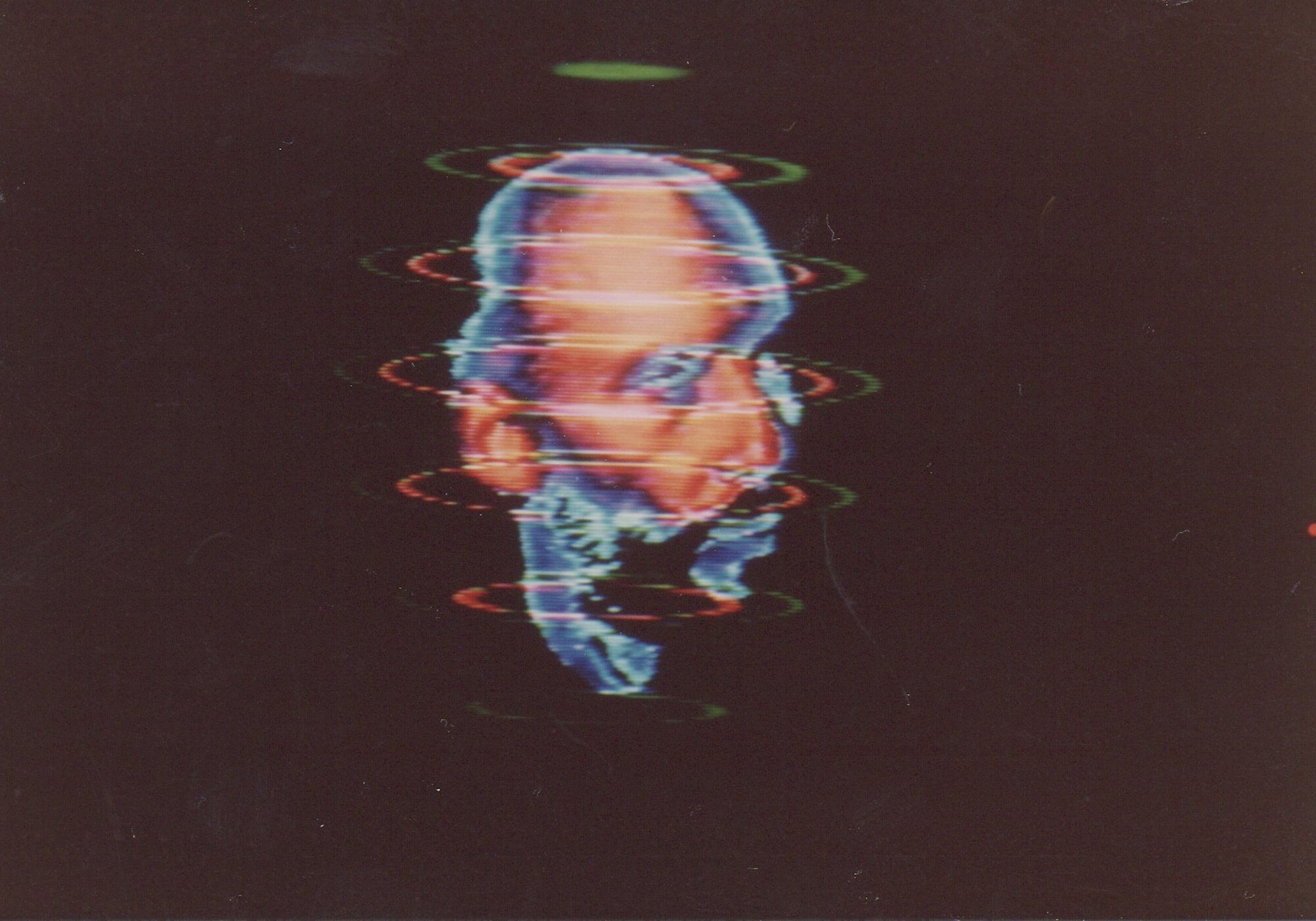

Around the 1970's I was very concerned with the questions surrounding the relationship between sound and image so I went to the US to see what was happening with video art over there. The grandmaster at the time was a Japanese by the name of Nam June Paik. I also met Ed Ernswhiller, who had done productions where the choreography was processed through an image synthesizer and which produced very unexpected results. Pretty much at the same time Ron Hays had made a video inspired by Wagner's Prelude to Tristan and Isolde where the image's development brings about a continual feeling of the infinite. For me, this output is very influential to the work in the music-and-image connection.

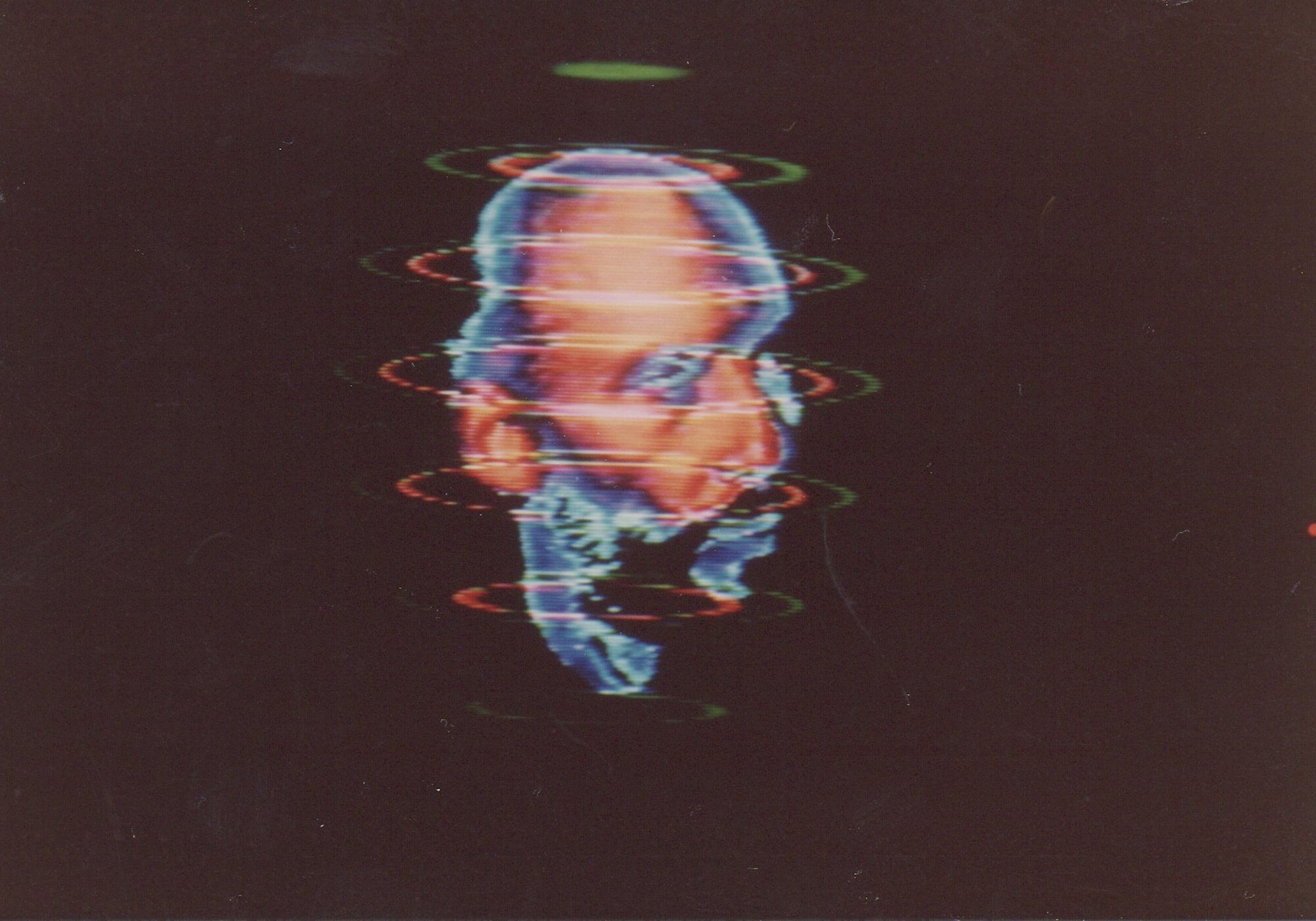

When I got back, I wanted to make some audiovisual experiments using pre-existing music. So, using images of my eye, or rather my eyes, I made L’Œil Ecoute with the Research Service's image synthesizer at the ORTF. The photos were taken by Valerian Borowczyck, a Polish filmmaker I was working with at the time. It was an investigation into the relationship between shape and substance. Using the image synthesizer, I processed the images from the eye photos together with the sounds. Later on, I wrote and co-produced L'Ecran Transparent wth José Montés-Baquer of the WDR (Westdeutscher Rundfunk) in Cologne.

I then tried one final experiment at the Research Service called Jeux d'Artifices. As its name implies, it's an illusory sound display which goes together with an illusory visual display to make a video about 12 minutes long. It was a very interesting experiment that I would've liked to take further, but I just didn't have the technical means.

The Matter of Space

How do you envision a piece's spatialisation when you perform it? Is it in view of making a show out of it or simply a moment to be lived through?

The word “show” makes me uncomfortable because there's a demonstrative side to it. I prefer the term “lived-through moment” because I never project the sounds the same way twice. When I'm in front of the mixing table during a concert, I evidently channel the sounds through specific speakers, going to the left, the right, on the sides, behind, etc., and I pair them. The sound could follow a trajectory, remain motionless within a speaker zone or even one pair of speakers. It's mediocre when certain composers, especially when they're first starting, open up all the faders and make very few alterations in overall volume. Worse still, the sound coming constantly from all sides is swamped. Then depending on the acoustics of the room you can even have cases where the reverberation or interference is so great that the listener can no longer distinguish any nuance.

Your Relationship with Technology

You lived through the great revolution from analogue to digital. Do you think these new tools have brought a new dimension to your music?

I believe I was the first at the GRM to buy my own equipment and have my own personal studio. I had to then teach myself how to work with digital devices. We all progressed on certain fronts and lost out on others, going from the scissors to the mouse. Analogue formats let you do things which became difficult and even impossible with digital. There are even sounds which you could create through analogue which you can't even get through digital, because of whichever program's design. Work habits being essentially different meant changes in technique for writing acoustically. Nonetheless you have to admit that the artisinal technique with scissors was quite tedious, whereas writing with the mouse is in some way quicker. The time between having an idea and realizing it is cut down, and so we're getting nearer to a real compositional act. But I can't use a new program without totally mastering all its functions. I like to go beyond the limits of ordinary instruments, diverting them from their recommended functions, which requires lots of time and effort to dominate. I don't actually use the machines for the effects they're capable of making but as tools for processing my sounds.

One Last Question

Given your age and experience, we might expect to see you looking to pass something on to others. You've passed on the passion for composing to some, of course. But you've never done any teaching, why?

First of all I'd say that I just don't have the educational touch. I'm not essentially a talkative person, nor very communicative. Whatever it is I have to say, I say doubtless more through my music than through any rhetoric. I feel forever unsatisfied, I feel like I'll have left something important out. I have a slow pace.

In Canada recently I gave a three-hour lecture at the Université de Montréal, after which I had to speak for another hour on the radio. I realized that I was wrong a lot of the time. Education works both ways – you learn a lot through the questions people pose you. Despite everything, I'm afraid of speaking and so I prefer to leave it to the music.